Italy’s Piracy Shield blocks IPs and domains within minutes, but measurements performed by researchers at the University of Twente and colleagues show broad collateral damage to legitimate services. We share the results of those measurements in the hopes of sparking a community discussion around the Piracy Shield initiative

The Italian anti-piracy platform, Piracy Shield, instructs ISPs to block reported IPs and FQDNs within 30 minutes. Supporters praise its effectiveness, citing numerous blocked streaming resources, while critics warn of overblocking issues, including disruptions to services like Google Drive.

Our study highlights key problems: extensive collateral damage to legitimate services due to shared infrastructure blocking; persistent evasion tactics like domain migrations and IPv4/IPv6 shifts; and risks from unintended impacts on critical services such as CDNs and DDoS protections.

To balance piracy control and Internet stability, we urge a shift to cautious FQDN-first methods, time-limited blocks, transparent reporting, and streamlined appeals for unblocking.

Why this is crucial for operators

Blocking live events is a race against the clock. Network operators are often asked to act within minutes, usually with little context and under significant operational pressure. As blocking expands to IP Space, the chances of targeting shared resources and overblocking, and the fallout it creates, only increase. Having visibility into the real footprint of these measures helps ISPs prepare, put safeguards in place, and work with regulators on solutions that reflect operational realities.

Piracy Shield in brief

Introduced as a legal requirement in 2023 and further developed throughout 2024–2025, Piracy Shield facilitates the swift blocking of IP addresses and fully qualified domain names (FQDNs) to protect live content, initially focused on football broadcasts and later extended to include a wider range of audiovisual material.

The list of blocked resources remains inaccessible to the public, although tools are available for checking individual resources. However, these do not support bulk exports. Several high-profile incidents brought attention to instances of excessive blocking affecting shared infrastructures such as CDN subdomains and IPs belonging to major providers. These cases have fueled ongoing discussions surrounding proportionality, transparency, and adherence to EU compliance standards.

Shedding lights on the blocklist

For months, the blacklist behind Italy’s Piracy Shield has remained in the shadows. AGCOM, the regulator in charge, has been repeatedly pressed by citizens and operators to release the list through FOIA-style requests. Every single time, the answer was the same: denied, with little to none explanation given.

The only official options were two lookup tools: AGCOM’s own portal; and a page run by Infotech, an Italian ISP. They let you check a single IP or domain at a time, but nothing more. No broader visibility, no transparency. Several operators referred of a GitHub repository that had been quietly publishing the full list of blocked IPs and domains since October 2024, updating it regularly.

Debate quickly followed: was this leak legitimate, or just random data? We decided to find out. By manually cross-checking entries from the leak against the official tools, we confirmed its accuracy. What emerged was the first validated dataset of Piracy Shield’s blocking activity, complete with dates, status changes, and even evidence of when certain resources were quietly unblocked. At this point, the black box wasn’t so black anymore.

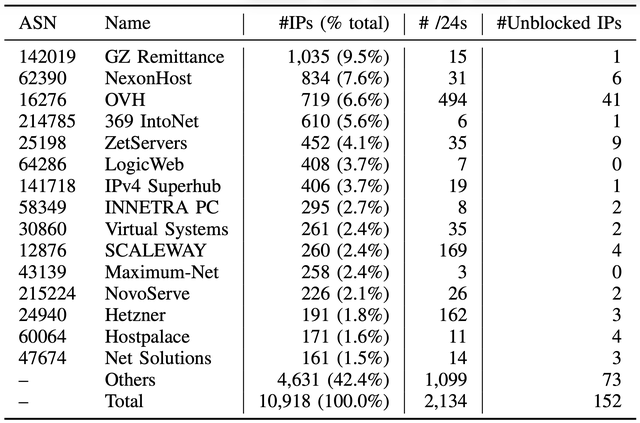

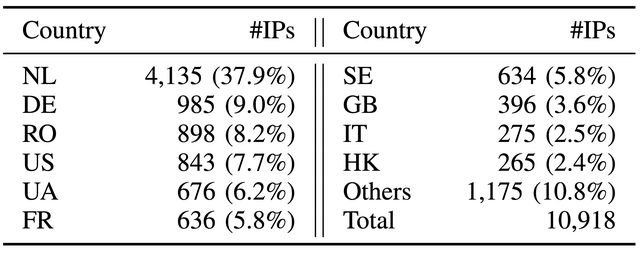

Hosting within EU dominate the piracy infrastructure

Once we had reconstructed the blocklist, the next question was obvious: where exactly are pirates hosting their infrastructure? We started with the blocked IPs. Out of just over 10,000 blocked addresses, one company alone accounted for nearly a thousand. The Top 10 providers together hosted more than half of all blocked IPs, showing a striking concentration of pirate activity around a small set of providers. But the real surprise was geographical. Nearly 77% of the blocked IPs were located inside the European Union, a jurisdiction where Italian copyright holders should, in theory, have more leverage to pursue illegal streaming operators through established legal and law enforcement channels, rather than relying on blunt blocking measures.

The picture became even more interesting when we looked at individual providers. Some, like OVH, showed a high number of unblocked addresses, a pattern suggesting that shared hosting environments, where legitimate services sit side by side with pirate streams, were frequently caught in the crossfire, leading AGCOM to later reverse some of its own blocks.

In search of collateral damage

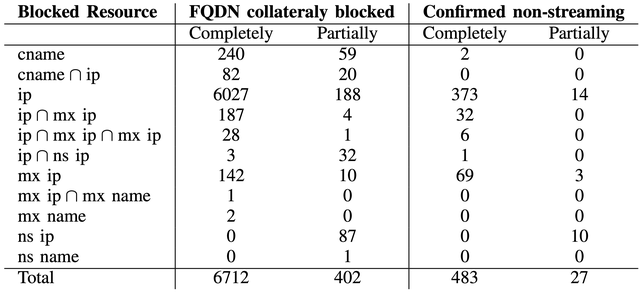

An IP address is rarely tied to a single resource. The same machine can run a website, a mail server, and a DNS service, or host dozens of unrelated websites through virtual hosting. On top of that, providers often recycle IPs, assigning them to new customers once they are freed. In the context of Piracy Shield, this creates the perfect storm. Since blocks are applied almost indefinitely, the natural churn of Internet hosting means that one decision to block a pirate stream can later drag down completely unrelated, legitimate services. To dig into this, we relied on two large-scale Internet measurements: the OpenINTEL DNS dataset and a full DNS measurement of FQDNs derived from certificate transparency logs. In those, we looked for signs of unintended damages: disruptions to web hosting, email delivery, and even the DNS itself.

IP-Level blocking causes major collateral damage

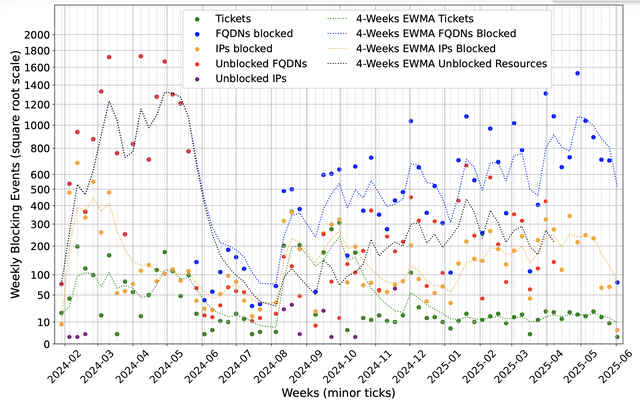

In June 2025, Piracy Shield was blocking 10,918 IPv4 addresses and 18,849 domains. From these, we measured collateral damage on 6,712 domains that were fully blocked and another 402 that were partially affected by those blocks. We checked these domains one by one, looking for active websites and classifying their content. We found that more than 500 confirmed websites unrelated to streaming were blocked, and over time the number of affected sites went into the thousands. Most of the damage came from IP-level blocking. In shared hosting, or when providers reassigned an IP after abuse, a single blocked address could take down dozens of unrelated domains. In some cases, one IP block was enough to silence entire groups of legitimate services.

Blocking goes beyond web services. It can disrupt essential infrastructure, for example, authoritative DNS or mail exchange (MX) servers caught in the block list can lead to outages. Even partial name-server blocking introduces vulnerability, particularly in configurations relying on single authoritative servers. Furthermore, blocks frequently affect anycasted DDoS-protection networks like StormWall, DDoS-Guard, and X4B. This is especially problematic during active DDoS mitigation efforts when sites are migrating to those IPs to counter attacks. One case even revealed a Google IP associated with a Piracy Shield related blocking page among the blocked addresses, underscoring how enforcement tools can unintentionally lead to self collateral damage.

Historical data shows prolonged exposure to collateral damage for affected domains, with median durations extending for months and average durations in the hundreds-of-days range. Many legitimate domain owners remain unaware they are impacted, often only discovering issues through user complaints or failed email transmissions originating from Italy.

Policy gaps encourage evasion strategies

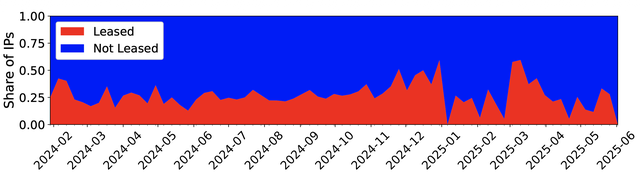

In this scenario, IPv6 remains practically untouched by enforcement efforts. Blocked FQDNs often adopt IPv6 post-blocking, creating direct bypass paths for users on public resolvers that do not implement the FQDN list. For IPv4, churn rates are high - many blocked FQDNs later resolve to new IPv4 addresses outside block lists. Additionally, approximately 25% of blocked IPv4 addresses come from leased address spaces, a conservative estimate. Variations in leasing practices across providers and the re-leasing of previously blocked addresses suggest the circulation of "polluted" ranges back into use.

A call to action

Our results on the collateral damages of IP and FQDN blocking highlight a worrisome scenario, with hundreds of legitimate websites unknowingly affected by blocking, unknown operators experiencing service disruption, and illegal streamers continuing to evade enforcement by exploiting the abundance of address space online, leaving behind unusable and polluted address ranges. Still, our findings represent a conservative lower-bound estimate. Our visibility into the global DNS is not exhaustive, and our damage assessment focused on HTTP(S) availability nowadays, likely missing cascading disruptions on other services like APIs, email, or databases that rely on direct IP connectivity.

The platform’s impact is multifaceted: economically, it disrupts legitimate businesses, from the Italian mechanics to international hosting providers who lose connectivity with their customers; technically, it risks systemic failure by blocking shared infrastructure like CDNs and DDoS protectors while polluting the IP address space for future, unsuspecting users; operationally it imposes a growing, uncompensated burden on Italian ISPs forced to implement an expanding list of permanent blocks.

The evidence of widespread and difficult-to-predict collateral damage suggests that IP-level blocking is an indiscriminate tool with consequences that outweigh its benefits and should not be used. Instead, AGCOM and copyright holders should prioritise legal pathways to pursue the majority of illegal streamers, many of whom operate within the European Union. Finally, we argue that the authority should publish the list of blocked resources immediately after enforcement, enabling third parties to vet the action and ensuring a responsive task force can promptly address unintended disruptions.

We hope that this work sparks a thorough discussion among Italian operators, AGCOM, and national policymakers on reconsidering the Piracy Shield initiative. This reflection must account for the significant collateral damage to legitimate infrastructure and the potential threat to national security the platform may pose. Ultimately, the challenge is not whether piracy should be fought, but how to do so without endangering the very principles and infrastructure that sustain the Internet as we know nowadays.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the ITNOG/RIPE communities for their early insights and all contributors who assisted in validating our measurement methodologies and datasets.

This summary highlights key points from our paper - 90th Minute: A First Look to Collateral Damages and Efficacy of the Italian Piracy Shield - accepted at CNSM 2025 and co-authored by Raffaele Sommese, Anna Sperotto, Antonio Prado, Jeroen van der Ham, Antonia Affinito.

Comments 3

Jan Žorž •

Technical solutions generally don’t solve social problems. They usually focus on symptoms, not causes. I hope that your country manages to see why shooting yourself in the foot is generally not a good idea.

Georg Later •

Thanks for shedding some light on this issue. After 25 years in the field, I couldn't have thought of a coarser, lazier and ineffective measure. Calling it a "technical solution" is insulting anyone who ever approached a problem from a technical standpoint: it's lobbysts pressing politicians pressing operators pressing citizens who ultimately pay the consequences of this mess. I wonder what would happen if, say, during a big live event someone would start streaming illegally from a bunch of /20s changing network every couple of hours. Who needs DoSers when you live in such a country? The "transparent authority" label on the very first link of the AGCOM homepage is the icing on the cake.

Named •

I think that governments shouldn't get involved with private sector issues like piracy. And they certainly must not start banning random IPv4 addresses, it will eventually disrupt a critical service with all hilarity ensued... I think that there is a harmful trend of governments forcing more and more of their decisions and opinions onto the internet, censorship, age verification, chat control, etc. The internet is supposed to be open and free, not locked down and controlled! If there is a legal issue like piracy or illegal content, use the proper legal channels to go after them. (Disclosure: I am sailing the seven seas for ethical and financial reasons. While i DO want to pay for certain things, there is just no way to get the money where it belongs. And paying legally makes the money end up in the hands of the bad guys. To me, the piracy "shield" appears as a weapon for the bad guys to steal my money.)