Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) are often overlooked in discussions about critical infrastructure. Yet their role in routing stability, local resilience, and digital sovereignty is undeniable. In this article, we explore what happens when IXPs fail, and why classifying them as critical infrastructure is not just a bureaucratic formality, but a systemic necessity.

What is an IXP and why does it matter?

An Internet Exchange Point is a physical interconnection facility where multiple Autonomous Systems (ASes) exchange IP traffic. Instead of routing traffic via expensive upstream providers, networks can peer directly, reducing cost, latency, and dependence on transit. Most IXPs consist of high-performance switching infrastructure, route servers, and optional measurement and monitoring tools.

Beyond technical efficiency, IXPs support national resilience, improve user experience by keeping traffic local, and serve as critical coordination nodes in times of crisis. Yet, despite their foundational role in Internet architecture, IXPs often operate in the shadows of public awareness and policy frameworks. As a result, their vulnerabilities tend to be underestimated.

The visibility paradox

Despite their crucial function, IXPs are often invisible in both public discourse and infrastructure policy. This "visibility paradox" creates three systemic risks:

- Economic optimisation over resilience. Traffic is increasingly routed through major IXPs due to cost and efficiency, concentrating risk;

- Dependency of smaller networks. Many small ISPs depend on a single IXP to access affordable connectivity and major content providers;

- Topological centralisation. A handful of physical IXP locations carry disproportionate amounts of regional traffic, creating structural vulnerabilities.

When IXPs go down: Real world examples

Let’s examine what happens when an IXP fails. Below are real incidents that illustrate systemic dependencies on these nodes.

Kenya (KIXP): Building resilience on a budget

In 2000, the Kenyan government attempted to block the launch of the Kenya Internet Exchange Point. Only strong advocacy from the local technical community preserved it. Since then, KIXP has reduced national transit costs by over 70% and improved routing stability despite limited resources.

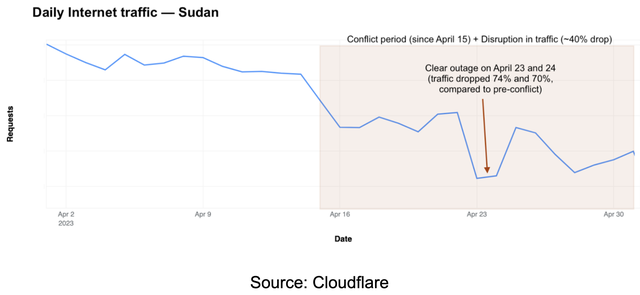

Sudan: Total national isolation

During the 2021-2023 Internet shutdowns, Sudan's lack of a robust local IXPs meant that even Internal traffic was cut off. The absence of domestic interconnection rendered the country completely dependent on international links, which were politically and technically severed.

Brazil (IX.br): State-led redundancy

Brazil’s IX.br, coordinated by CGI.br, operates 35 IXP locations. During the 2020 pandemic surge, its wide geographical coverage helped absorb massive traffic increases. Its model proves that public coordination and decentralisation enhance systemic resilience.

Germany (DE-CIX): Power failure, wide impact

In 2018, a power outage at Interxion FRA5 (hosting a major DE-CIX switch) caused partial IXP failure. The resulting loss of BGP visibility affected routes across Europe. Even with built-in redundancy, this incident highlighted how dependent many ASes are on a single physical location.

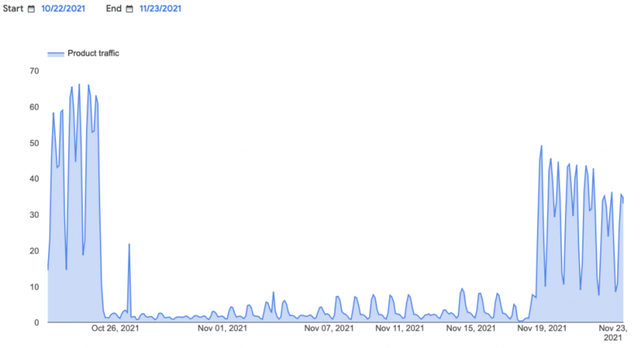

United Kingdom (LINX): Wide-scale reconvergence

A 2021 software fault at LINX caused traffic to reconverge at scale, hitting smaller ASes hardest. While routing recovered, the temporary instability caused degraded performance and demonstrated how IXP events cascade beyond borders.

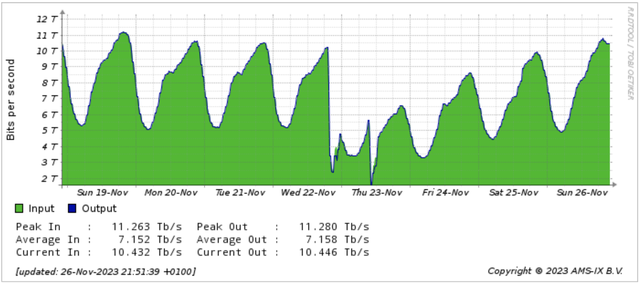

Netherlands (AMS-IX): Traffic collapse

In November 2023, AMS-IX experienced two service interruptions totalling over five hours. During the outage, traffic dropped from 10 Tbps to 2 Tbps. The effects were felt across European providers reliant on the exchange.

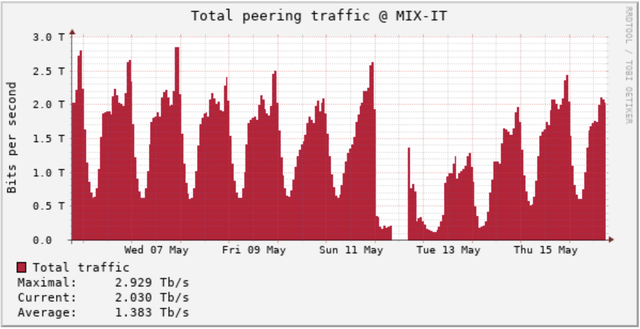

Italy (MiX): National impact

On 12 May 2025, a fault at the Milan Internet Exchange (MiX) disrupted reachability of several local services, leading to slowdowns and outages nationwide. This reinforced MiX's critical role in Italy’s Internet architecture.

Takeaways

- IXPs are not merely technical optimisers, they are systemic stabilisers.

- Failure at a single IXP can trigger large-scale routing issues, congestion, and degraded services.

- National Internet resilience is deeply intertwined with the robustness, governance, and redundancy of local IXPs.

IXPs and resilience: From crisis buffer to digital sovereignty

IXPs as buffers in times of crisis

When thinking about resilience on the Internet, most discussions revolve around backbone providers, submarine cables, or DNS root infrastructure. Yet, Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) quietly play a key role in buffering crisis scenarios, localising traffic, and preserving critical connectivity, especially under stress.

Local traffic, local impact

IXPs dramatically reduce dependence on long-haul transit routes. By allowing local networks to exchange traffic locally, they provide both latency improvements and a powerful structural advantage: autonomy. In ordinary times, this means efficiency. In times of crisis, from war to natural disaster, this means resilience. During the early stages of the war in Ukraine, for example, local operators managed to maintain partial Internet functionality in several cities thanks to local peering. Traffic that would have otherwise required routing through foreign transit providers remained within domestic IXPs, decreasing exposure and dependency. Conversely, countries with underdeveloped peering ecosystems, or where interconnection is over-centralised, are more exposed to routing fragility.

IXPs as shock absorbers

The impact of external shocks, energy failures, cyberattacks, embargoes, is often amplified when IXPs are missing or poorly governed. Let’s take some recent examples:

- Kenya: A power outage in 2023 disrupted Internet access countrywide. While multiple providers had redundant international capacity, the absence of robust local peering meant that local traffic had to rely on external routes, which degraded performance and reachability.

- Sudan: Recurrent outages and state-mandated outages have shown that centralised international dependencies make restoration harder. A stronger local IXP ecosystem could have helped mitigate isolation.

- The Iberian Peninsula (2025): A major outage revealed that Portugal’s Internet traffic dropped by up to 90%. Spain’s traffic, while impacted, held up better, partly due to its stronger IXP footprint, including Madrid-based Espanix and DE-CIX Spain.

These cases illustrate that IXPs do not just route packets, they absorb impact.

Strategic sovereignty

Beyond resilience, IXPs play a less obvious but equally critical role: digital sovereignty. A country with strong, neutral IXP infrastructure:

- is less dependent on foreign upstream providers;

- can enforce national security policies more effectively;

- gains visibility into local traffic patterns;

- enables regional development and inclusive access.

The Russian-Ukrainian conflict underscored this. In Russia, policy-level centralisation was accompanied by an infrastructural reshaping of IXP control. In Ukraine, the need for network decentralisation and agile failover plans became a survival requirement. In Brazil, debates around neutrality and national peering have led to efforts to strengthen IX.br as a backbone of sovereignty, not just performance.

The danger of centralised peering

Sovereignty and resilience are at risk when IXP infrastructure is concentrated in a single entity, especially without regulatory checks or open governance. This includes:

- single points of technical failure;

- abuse of dominant market positions;

- lock-in effects for smaller networks;

- limited data observability for national CERTs and researchers.

A multi-IXP ecosystem, governed by transparent processes and federated models, reduces these risks. Neutrality isn't just a principle, it's a structural necessity.

Recognising IXPs as critical infrastructure: What needs to change

Despite their central role in routing stability and local interconnection, Internet Exchange Points are still rarely classified or treated as critical infrastructure. This gap creates regulatory blind spots and operational fragility, especially in countries where one IXP dominates the national traffic exchange. In this final part, we look at the governance, policy, and operational frameworks that must evolve to ensure IXPs are recognised and supported as the resilient backbone they already are.

Governance: Transparency before scale

Many IXPs start small, often as collaborative efforts between local ISPs, universities, or NOGs. As they scale, however, their governance model may remain informal or opaque. This creates risks when traffic concentration grows.

Critical IXP governance principles should include:

- neutral ownership (no single commercial entity with veto power);

- multistakeholder boards, including operators, academia, civil society;

- published traffic statistics, membership policies, and pricing models;

- clear failover plans and infrastructure redundancy.

Without these, IXPs become invisible single points of failure, technical and institutional.

Technical hygiene: Routing security and observability

For IXPs to be resilient, they must also be secure and observable. This includes:

- mandatory Route Server filtering with prefix and AS-path validation;

- RPKI-based filtering and support for BGP monitoring tools;

- public Looking Glass or IXP Manager views;

- participation in the MANRS IXP Programme.

These are not “nice to have” extras. In a world of BGP leaks, hijacks, and targeted attacks, they are baseline requirements. Greater observability also enables national CERTs and researchers to act faster during incidents, from misrouting to DoS attacks affecting IXP-connected networks.

Policy: From recognition to resilience

Very few national legislations include IXPs in their critical infrastructure lists, often focusing instead on physical cable systems, data centres, or DNS infrastructure. Yet, the strategic value of IXPs calls for their inclusion in:

- national cybersecurity strategies;

- regulatory frameworks for network resilience (e.g. NIS2/CER);

- funding schemes for disaster preparedness and infrastructure audits.

At the EU level, IXPs could be acknowledged within cross-border infrastructure schemes such as CEF Digital, or monitored within ENISA’s CIIP strategies.

A federated model for continental resilience

Europe’s IXP ecosystem is dense but fragmented. This is a strength, no central choke point, but also a coordination challenge. We propose:

- a European IXP Resilience Observatory, combining RIPE NCC, Euro-IX, ENISA, and operators;

- a shared incident response framework for IXP-targeted disruptions;

- optional audits and federated monitoring of Route Server practices.

This doesn’t mean replacing existing governance. It means reinforcing it, the way IXPs themselves reinforce the Internet.

Final thoughts

IXPs are not “just switches.” They are interconnection commons, supporting not only traffic but the values of the Internet itself: openness, decentralisation, and collaboration. Recognising them as critical infrastructure is not a symbolic gesture. It is a technical necessity.

Treating IXPs as systemic stabilisers means investing in their resilience, governance, and neutrality. From the local network that keeps a small town online during an outage, to the continent-wide coordination that buffers entire regions from geopolitical shocks, IXPs are quiet guarantees of continuity. Their impact is visible every time packets stay local instead of traversing oceans, every time a crisis is absorbed instead of amplified.

Future-proofing the Internet demands that IXPs are embedded in national resilience strategies, supported by transparent governance, and integrated into European digital sovereignty efforts. This includes regulatory recognition, funding for redundancy, and cross-border collaboration frameworks. At a time when connectivity is critical to every aspect of society - economy, democracy, security - overlooking IXPs means leaving a blind spot in our collective defences. A resilient Internet is not possible without resilient IXPs.

The path forward is not to centralise more traffic in fewer places, but to build diverse, neutral, and well-governed interconnection points that reflect the same decentralisation that made the Internet succeed in the first place.

Comments 7

peter dawe •

Antonio, I together with Keith Mitchell created LINX in the very early days of the Internet. A key factor you miss is actually the reason we created the LINX. It stops large ISPs from extorting "Taxes" from smaller ISPs. The key here is if a large ISP seeks to restrict traffic, the IXPs provide a route around the blockage. We can see how Deutsche Telecom have tried repeatedly to muscle traffic to their advantage and have been repeatedly thwarted. might form a cartel to maximise their profits. The agreements that are the basis of the whole commercial Internet are underwritten by the IXPs. I have an incomplete paper on IXPs available which explain much that may have been forgotten

Antonio Prado •

Thank you, Peter, for your comment and for reminding us of the foundational motivations behind the creation of LINX. Your point is absolutely crucial: IXPs are not only about performance and resilience, but also about market fairness and interconnection freedom. It would be very valuable to include historical reflections like yours: if you’re open to sharing the incomplete paper you mentioned, I’d be keen to read it and possibly reference it in future revisions or spin-offs of the article. Thank you again for your contribution and for helping make the Internet what it is today.

Flavio Luciani •

You're absolutely right, Peter, and it's something I usually emphasize, how alternative operators in Europe, in the late '90s, were able to reduce their dependence on incumbents precisely thanks to interconnecting with each other within the very first emerging IXPs. Thank you for pointing it out!

Antonio M. Moreiras •

I want to thank you for your article and for the mention of IX.br, and confirm that the article’s description about its wide geographical coverage helping to absorb massive traffic increases is accurate. I would also like to emphasize that the adequate scaling and dimensioning of the largest IXPs: São Paulo, the largest in the world, Fortaleza, and Rio de Janeiro, has been fundamental in supporting the growing traffic demand. However, I want to clarify that stating the coordination is public or state-led is not correct. CGI.br works in the public interest, as does NIC.br, but the coordination of IX.br is multistakeholder through CGI.br, with balanced participation from the public sector, private sector, civil society, and academia. I also want to clarify that no government funds are involved in IX.br. NIC.br is a private non-profit entity that manages IX.br and other initiatives, funded with private resources mainly from the registration of .br domains, while following the guidelines established by the multistakeholder council CGI.br, which guides public policies for the Internet in Brazil. I remain available for any further clarifications.

Antonio Prado •

Muito obrigado, Antonio, tanto pela leitura quanto pela importante correção. I’ve now updated my internal notes to reflect this. I’m grateful for your detailed comment, and I will make sure any future references distinguish clearly between multistakeholder coordination and state operation.

Flavio Luciani •

Thank you very much for the comment Antonio. It would indeed be very useful to have a detailed analysis of the various IXP governance models around the world. Perhaps it could be a project that the four associations could undertake (Euro-IX, LAC-IX, AP-IX and AF-IX). Having this taxonomy, in my opinion, would be useful or at least interesting to analyze, also to better understand which forms of governance are most commonly used and the reasons behind the choice of one model over another.

Flavio Luciani •

Thank you very much for the comment. It would indeed be very useful to have a detailed analysis of the various IXP governance models around the world. Perhaps it could be a project that the four associations could undertake. Having this taxonomy, in my opinion, would be useful, or at least interesting, to analyze, also to better understand which forms of governance are most commonly used and the reasons behind the choice of one model over another.