It's time for another Internet Governance Forum! IGF 2022 takes place this week in hybrid format. This year's overarching theme is "Resilient Internet for a Shared Sustainable and Common Future". Check this page for regular updates from RIPE NCC staff on the issues, arguments and opinions discussed at the meeting.

The topics of this year's agenda are grouped into six categories, aligned with the UN's envisioned Global Digital Compact: connecting all people and safeguarding human rights; avoiding Internet fragmentation; governing data and protecting privacy; enabling safety, security and accountability; and addressing advanced technologies, including AI.

As the event goes on, we'll be sharing key moments and takeaways from the sessions we attend.

Does this sound interesting and do you want to actively participate in the IGF sessions? It's still not too late to register. The event runs from 28 November to 2 December. Check out the interactive program and if you've missed any interesting session, take a look at the video recordings.

Day 4: Voices from the IGF

As with any conference, a large part of the work at the IGF takes place outside of the formal sessions. We had a series of conversations with attendees from different stakeholder groups about what they found important and relevant at this IGF.

There were a few recurring sentiments – it was important that the IGF was taking place in Ethiopia, on African soil. Africa has the largest youth population that has not yet connected to the Internet - as Caleb Ogundule pointed out - and it’s essential that this booming population group gets meaningful access to the Internet, and also gets involved in these discussions.

An area where the IGF has been very successful is in increasing the participation from younger groups. Emilia Zalewska shared that the Youth IGF submitted 13 proposals for sessions, of which 11 were accepted. Throughout the IGF, we also saw members of the Youth IGF chairing sessions and moderating discussions.

Youth voices should be heard! We spoke to Emilia Zalewska (@emiliahzalewska), one of the organisers of the #YouthIGF about her thoughts on the #InternetGovernanceForum #IGF2022 #voicesfromtheIGF pic.twitter.com/LnKtXwV8nj

— Number Resource Org (@theNRO) December 1, 2022

Speaking about having a seat at the table, Baratang Miya, the CEO of GirlHype shared statistics on gender disparity in accessing the Internet. She organised the Women’s Summit at the IGF to make sure that women had a voice and could share their input.

Fiona Asonga, CEO of the Technology Service Providers of Kenya (TESPOK), had a message for the tech community. She said that the focus on human rights at this very diverse, multistakeholder forum showed that the tech community needs to be aware of what civil society expects from them.

The #InternetGovernanceForum (@intgovforum)brings together diverse stakeholders. We spoke to Fiona Asonga, CEO of @TESPOK_KENYA about her views on the #IGF2022 and some key takeaways for the Internet technical community. #voicesfromtheIGF pic.twitter.com/wgXSIK0Fb6

— Number Resource Org (@theNRO) December 1, 2022

IGF Multistakeholder Advisory Group Member, Bruna dos Santos, added that it was great to be back on site after such a long time at virtual events due to COVID-19 and to be back on African soil.

Speaking on youth engagement, Caleb Ogundele, President of the Internet Society Nigeria Chapter, said the IGF youth were not only present but were fully participating in discussions as well as raising important points around the gig economy and digital rights issues. He added that rather than being a talking shop, there were many ICT ministers speaking at high level meetings leading to policies being shaped by IGF conversations.

Day 3: Fighting Cybercrime: Attribution and Accountability

The Council of Europe organised an engaging session on handling e-evidence globally. Cybercrime affects everyone: individuals who see their human rights violated, businesses who suffer financial and reputational damage to public bodies and critical infrastructure. It damages democracies through election interference and misinformation. It undermines the core values of our society - democracy, human rights, rule of law - and poses a threat to international peace and security.

Efforts to bring cyber-attackers to justice face chronic challenges. Less than 0.1% of cybercrimes are successfully prosecuted, which points to a major accountability gap. A big part of the challenge comes from difficulties in accessing electronic evidence. This is critical to detecting crimes in the first place, attributing crimes to the perpetrators, and ensuring prosecution. But obtaining e-evidence is a complex task. E-evidence is inherently volatile. It is easy to delete or alter. Often it's stored in foreign sometimes-multiple, sometimes-unknown jurisdictions requiring effective international criminal justice cooperation. Evidence is also often stored by the private sector, which means there need to be effective ways for the criminal justice system to cooperate with them. All this requires effective safeguards to ensure that government-to-government and public-private cooperation is in line with rule of law standards and human rights principles. This raises a number of different issues:

- How can we improve attribution of cyberattacks and other crimes involving e-evidence?

- What is needed to ensure perpetrators of such acts are held accountable?

- What tools do we have to obtain e-evidence and how can we guarantee human rights and rule of law are upheld?

Pay Ling Lee, Interpol, shared with us the findings of the Global Crime Trend Report. Ransomeware remains a top concern throughout the world, followed by fishing, online scams, and computer intrusion (hacking). There is also an increase of child sexual exploitation and abuse. The report also outlines a number of challenges that law enforcement faces when solving cybercrime such as:

- Having adequate access to relevant information. Cybercrime is often underreported leading to lack of clear appreciation of the cyberthreat landscape which leads to an inadequate allocation and prioritisation of recourses by governments.

- Other entities often possess the data and know how. Usually CERTS (Computer Emergency Response Teams) are the first responder to cyber incidents. If law enforcement are a part of this process from the beginning they could make sure more emphasis on securing digital evidence.

- There are already some legislative and technical tools available to secure digital evidence such as Mutual Legal Assistance treaties and the Budapest Convention. The UN is working on a stronger international convention dealing with digital crime and e-evidence.

- While many jurisdictions have set up specialised units to deal with cybercrime, first line responders should possess the adequate knowledge and expertise in order for them to immediately secure e-evidence (otherwise it might be too late once the specialised units get involved).

Esteban Aguilar Vargas, Public Ministry Costa Rica, told the room of the heavy ransomeware attack that his country experienced in April and May 2022. It affected national entities and government structures - especially the Ministry of Finance and the public health system - and forced the country into a state of emergency. The attack was a lesson: 1) that more priority and resources needs to be put into protecting critical government entities; 2) that more international cooperation is needed to swiftly bring perpetrators to justice (the help of the US and Spain was very important in this year's case); and 3) that their legislation needed to be updated to allow them to investigate at high speed.

Alexander Seger, Council of Europe, spoke of the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime, which provides the most comprehensive global framework to obtain e-evidence. It gives law enforcement the power to order the preservation of computer data, to seize computer data and systems with regard to e-evidence, to intercept traffic data and content, and so on. It has been a success, with 68 parties having signed the treaty - Brazil doing so yesterday. The session finished with a call to action to governments from all over the world to join the 120 counties which have already aligned their domestic legislation with the treaty.

- Gergana Petrova (1 December 2022, 15:00 UTC)

Day 2: A kaleidoscope of views on fragmentation

The discussion on one of the main themes of this year’s IGF – avoiding Internet fragmentation was perhaps (ahem) a bit fragmented… One of the key issues for the Policy Network on Internet fragmentation to begin with is to agree on a definition and scope of fragmentation. Is it fragmentation only if it takes place at the technical layer? What about differences in user experience, that can vary by geography or by platform? What do we do about technological evolution that results in fragmentation? Is there a difference between political choices and policy impacts? For a more detailed overview of Internet fragmentation, read this article by Chris Buckridge, who incidentally also moderated the discussion at the IGF.

Speakers included Amandeep Gill, the UN Tech Envoy, Tatiana Tropina, a researcher at the Leiden University, Edmund Chung, ICANN Board Member, Emilar Gandhi from Meta, Raul Echebarria of ALAI and Sheetal Kumar, Global Partners Digital. Everyone agreed that the user experience of the Internet is indeed fragmented – chiefly due to differing views on the content layer.

Raul Echebarria pointed out that fragmentation at the technical level is the unintended result of policy decisions rather than politics (unlike Internet shutdowns or content restrictions). He gave the example of content filtering, which sounds simple, but can be implemented in many different ways. Laws might require ISPs to block illegal content for instance, but the way it's carried out at a technical level might vary by ISP, resulting in a fragmented user experience, even within a country. Speaking of technical fragmentation, Edmund Chung pointed out that the decentralised nature of the Internet shouldn’t be considered fragmentation. However, he added that another form of technical fragmentation can occur as the Internet evolves from one protocol to the next.

Tatiana Tropina also commented that Internet shutdowns should not be included under the umbrella of Internet fragmentation but rather be recognised as a violation of human rights. Shutdowns do not change the user experience, they simply do not allow users to experience the Internet.

The speakers were in agreement about the need to maintain the technical layer that allows us to have one open, interoperable, interconnected Internet through the multistakeholder model, and acknowledged the challenges posed by efforts at digital sovereignty. The importance of forums like the IGF was acknowledged as there is already a strong multistakeholder model of governance for the technical layer of the Internet. There was also general consensus that efforts have been made to water down this model, driving home the need to continue to engage at the multistakeholder and multilateral levels, with Amandeep Gill suggesting that the Global Digital Compact might offer a way forward. Whether the Global Digital Compact can live up to its promise to ensure a truly open and interoperable, unfragmented Internet will probably be one of the challenges for the year ahead.

- Ulka Athale (30 November 2022, 18:00 UTC)

Day 2: Reflections on Internet sanctions

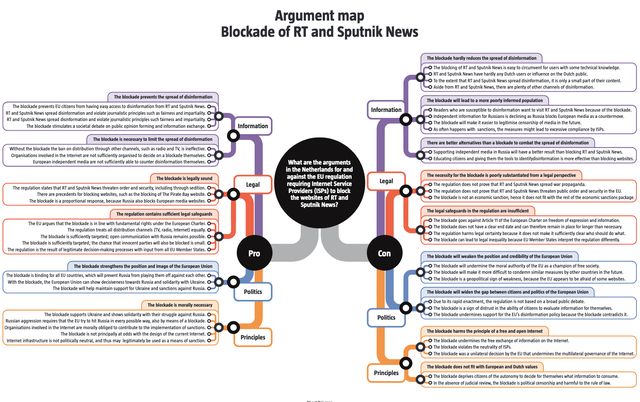

Recent events in Ukraine have put a spotlight on fundamental questions around the use of governing bodies imposing Internet sanctions. RIPE NCC's Bastiaan Goslings joined a panel to reflect on an arguments map put forward by two Dutch organisations - AMS-IX and ECP. The map makes a case for and against EU regulations requiring ISPs to block RT websites and Sputnik News and was put together with a broad group of experts from companies, governments, knowledge institutions and non-governmental organisations.

Click here for a pdf version of this image

The discussion provided for some insightful reflections beginning with the infringement of sanctions on the multi-stakeholder model. The Internet is a shared resource which belongs to nobody and belongs to everybody. Actions that disconnect users and threaten the Internet as public resource will in turn affect networks far beyond the borders of the countries being sanctioned, fragmenting the Internet. The reason the Internet is so seamless is because it doesn’t have boundaries. Precedents are set that undermine the multistakeholder process.

The rushed process which produced an overly broad set of sanctions has a lack of clarity for ISPs on implementation. The regulatory authority wasn’t mandating what to do with blocked websites and how long ISPs were meant to comply with this – until the war is over? How do you comply and how long are you supposed to comply with the sanctions were practical questions without answers. The sanctions happened over a weekend with EU Members States unanimously deciding that this had to happen. The EU Parliament was only informed, which leads some to question their legitimacy and proportionality. Human rights are not absolute – there is always a balancing act that takes place. The fact that the EU prioritises public order and security of European citizens over freedom of expression and information sharing may not be seen as a sufficiently substantiated argument.

- Karla White (30 November 2022, 17:00 UTC)

Day 2: Promoting Internet standards to increase safety and security

An interesting discussion focussed on how to increase the use of modern Internet standards to make the Internet more accessible, safer, and more reliable for everyone. Gerben Klein Baltink (Dutch Internet Standards Platform) talked about internet.nl, an online testing tool that helps check whether your internet is up to date: does the website you are visiting, your email-provider, and your Internet connection comply with modern open Internet standards such as IPv6, DNSSEC, HTTPS, STARTTLS, DANE, DMARC, DKIM, SPF, and RPKI. If they do not, the tool will suggest what can be done about it.

Bart Hogeveen (Australian Strategic Policy Institute, ASPI) talked about aucheck.com.au, which launched earlier this year. While the Dutch chose a ‘naming and shaming’ approach of showing which providers are more, or less, compliant, this is not a feasible for Australia. Furthermore, a lot of information has been added specifically for a non-technical audience, focussing on small and medium enterprises. As in the Netherlands, in Australia efforts are ongoing to establish a multistakeholder platform for discussion and to make people more aware of the importance of using modern open internet standards.

Gilberto Zorello (NIC.br) presented the experience in Brazil with the "Test the Patterns (TOP)" initiative. Launched in December 2021, it gives a stamp to providers with high scores. Despite the challenge to make all the different open source elements for the website to work together, different departments of NIC.br are involved in maintaining and updating TOP. Partnerships have been established with ISP associations, and the tool is presented at tech events. NIC.br sees that already parties are adopting standards because of its test results.

Maarten Botterman spoke on the work being done by the Global Forum on Cyber Expertise. They too focus on standards deployment as part of their Internet Infrastructure Initiative and advocate the benefits of a local implementation of internet.nl code. But Internet.nl is more than the website, it is a public private platform: government, industry, private sector, academics and NGOs came together to discuss what is important. Maarten noted that in Africa the challenge is not security as such but getting online in the first place. Like in India, where they are considering their own situation, keeping in mind local and regional needs. As mentioned, naming and shaming might work in the Netherlands -- but not elsewhere.

The internet.nl software is now structured in way to make it more usable and tailor it for your local language. So, feel free to reach out to the GFCE. There is a handbook on Internet standards, and the Dutch platform is more than willing to help.

Finally Gerben referred to the configuration of websites and mailservers that improved in the Netherlands because of test results. When your neighbour or competitor is doing better than that works as an incentive to improve yourself. Gerben stated that the UN needs to be called on to accelerate uptake of relevant open standards globally. For instance, in context of the Global Digital Compact.

An audience member asked why local communities decide what standards to include in a testing tool (e.g. in Australia DNSSEC is not included). Maarten Botterman responded that in the Netherlands banks were severely affected by DDoS attacks, which lead to the implementation of DNSSEC being accelerated. In Australia email from parliamentarians was compromised, which lead to email security been given priority. So, standards are a living thing. Internet was built to be used, not to be ex ante secure. Things have changed and so have priorities, and priorities will differ in different regions.

- Bastiaan Goslings (30 November 2022, 14:00 UTC)

Day 2: Next hop Alpha Centauri?

The future on interplanetary networking session took the discussions on Day 2 of the IGF into outer space. Vint Cerf walked the audience through the history and development of interplanetary networking.

Work in this area began in 1998, shortly after the Pathfinder landed on Mars. If interplanetary networking has been around for over two decades, why are we talking about this now? Back in 1998, a group asked what would be needed in 25 years. With that milestone reached in 2023, and a renewed space race, this time involving corporate interests, there seems to be a fresh impetus to work on the interplanetary network.

A new suite of protocols has been under development at the Internet Engineering Task Force (the IETF) called the ‘Bundle Protocol’. One of the fundamental issues with interplanetary connectivity might sound fairly obvious – the distances involved are astronomical. A round trip to Mars for a data packet could take anywhere between 7 and 40 minutes, which means that the protocol used needs to be able handle delays very well. The Bundle Protocol is currently on version 7 (BPv7) and is being worked on in the IETF under RFC 9171. One of the key features of this protocol is Delay and Disruption Tolerant Networking, which requires storing data and then forwarding it when connectivity is available (store and forward).

Who would issue the IP addresses needed to run interplanetary networks? According to Vint, an open question is whether we would want to use the same set of IP addresses for the entire solar system. One possibility is that each planet or moon or asteroid has their own independent internet (lowercase “i” used deliberately here), with distinct and separate IP address allocations for each of the outer space internets. These internets could be connected together using the Bundle Protocol. At this point, they envisage using Autonomous System Numbers except it’s possible that each planet has different ASNs.

Routing is another challenge in the Interplanetary Internet. A good analogy for routing on the Internet compared to routing on the Interplanetary Internet is comparing driving on highways to flying. Routing on the Internet is like driving; if one road is congested, you can take another one and keep moving. Routing on the Interplanetary Internet is like flying, when you fly long distances and have a stopover, you’re obliged to stop completely for a few hours until your next flight – at which point you’ll cover long distances again. On the Internet packets get thrown away if there’s no route to get to the destination. In the Interplanetary system, data will have to be stored in routers and congestion control is much harder in such a system.

There were further discussions on more political topics like the militarisation of space, the Artemis Accords, corporate interests and patents affecting open source development, inclusivity and the potential widening of the digital divide. For the RIPE community, perhaps, we need to ask if the sky really is our limit.

- Ulka Athale (30 November 2022, 13:00 UTC)

Day 1: Chris Buckridge on the Youth IGF Daily Briefing

In Day 1 of their daily briefings at IGF 2022, the YouthIGF talked to Chris Buckridge (Advisor to the RIPE NCC Managing Director and UN IGF MAG Member) and Menelik (Youth IGF leader from Ethiopia).

Day 1: Technical Standard-Setting and Human Rights

A good discussion took place on the collaboration between the technical community, academia and civil society on standards setting while making a concerted effort to consider human rights. The panel focused on how different communities and stakeholders can come together, the challenges and proposed several ways forward:

- Standards Developing Organisations (SDO) should be open and inclusive with stakeholders being able to have a seat at the table and voice their concerns when it comes to standard setting without opaque documentation and paid memberships

- The final outcomes of developing technical standards should be consensus-based including issues around human rights

- Fundamentally, Internet infrastructure and architecture was designed with human rights in mind from the beginning but now it’s evolving and sometimes conflicts with human rights

- As different experts speak different languages, there needs to be a concerted effort to bring together different communities and create a common ground where each can understand the other

- There was some consensus that an annual workshop with academics and SDO leaders could come together and tackle the challenges and create space to reach high level alignment

- There are explicit and implicit barriers to civil society participating in standard setting, the IETF has a practice of radical transparency with easily accessible mailing lists, documentation and meetings – other SDOs need to follow suit

- Lars Eggert, IETF, shared a case study where the IETF had been approached by human rights academics and advocates. A research group was created and now they provide feedback while the technology is being built and propose changes – this could be used as a blueprint for other SDOs.

- Karla White (29 November 2022, 19:00 UTC)

Day 1: What can we expect from the IGF 2022?

We’re going to hear a lot more about the Global Digital Compact over the coming months. The 17th Internet Governance Forum - and the third one to take place on the African continent after Sharm el Sheikh (2009) and Nairobi (2011) - was officially opened today. This year’s IGF has five main themes:

- Connecting All People and Safeguarding Human Rights

- Avoiding Internet Fragmentation

- Governing Data and Protecting Privacy

- Enabling Safety, Security and Accountability

- Addressing Advanced Technologies, including AI

While RIPE NCC staff will do our best to cover the major discussions, our focus at this IGF will be on covering discussions around avoiding Internet fragmentation, with Chris Buckridge moderating Day 2’s session on avoiding Internet fragmentation, and Bastiaan Goslings speaking on Day 4’s session on the geopolitical neutrality of the global Internet.

During the opening plenary UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres addressed the audience via a video message. The theme for this year’s IGF is a “Resilient Internet for a Shared Sustainable and Common Future”, and the forum will serve as a consultation for the Global Digital Compact, “a framework for an open, free and secure digital future” – expected to be agreed on at the UN Summit of the Future next year.

An important theme at this IGF is connecting all people and safeguarding human rights, summarised by Guterres’s statement that “The future will be digital, but the future of digital must be human-centred.” As another speaker on Day 1 stated, the Internet is no longer a privilege, but a necessity.

Guterres also reminded us that although Internet use has come a long way, 2.7 billion people have never been online. How the digital divide can be closed is likely to be an important discussion at this IGF - the IGF’s factsheet says that only 21% of people in Least Developed Countries (LDCs) enjoy access to the Internet, compared to 87% in developed countries. The Nobel Peace Prize laureate and Prime Minister of Ethiopia, Abiy Ahmed Ali, gave a more cautious address, acknowledging the contribution of the Internet to social development but highlighting issues with giant platforms with access to huge amounts of data that can turn from “gateways” into “gatekeepers”. Crucially, he called upon the IGF to go beyond reflections and to produce “tangible, pragmatic and implementable proposals” to achieve the goals of a resilient, safe, global Internet community.

Vint Cerf also spoke during the opening session, reiterating that the role of the technical community is to work towards realising the system that we all want, and articulate the features that it should encompass. In this context, it will be interesting to see how the dialogue with the technical community will follow. As Vint Cerf put it during his opening address, “It’s time to roll up our sleeves and get down to work.”

- Ulka Athale (29 November 2022, 14:00 UTC)

Day 0: Understanding Internet Fragmentation - Concepts and their Implications for Action

The concept of Internet fragmentation is a big theme at this year’s IGF. A panel of experts tried to pin down exactly what fragmentation means since William Drake noted there’s still no real consensus on what the definition of fragmentation actually is.

Andrew Sullivan kicked off the session by defining fragmentation as a spectrum. There was general agreement among the panellists on this and the discussion of a spectrum gave way to an interesting panel talk on framing fragmentation across three main categories: fragmentation from the user perspective and data; ruptures in the technical infrastructure; and fragmentation in the governance layer.

Much of the discussion focused on how to continue to foster globalised exchanges across a spectrum of fragmentation and the significant effect of nation states imposing their frameworks on the networking environment.

Some of the speakers touched on the ‘why now’ of Internet fragmentation. Wolfgang Kleeinwachter noted how time has changed the relationship between the technical and political layers of the Internet. The fundamentals of a global Internet were set out in the ‘90s with aspirations that the technical layer would influence the policy layer. Now the policy layer was affecting the technical layer and the fundamentals of the global network of networks was being threatened. New policy objectives and domestic laws are interfering with data routing and new regulations risk fragmentation of the Internet.

A word which also cropped up throughout the session was interoperability. The term had been mentioned by two superpowers - in both the declaration from the White House and the White Paper published in Beijing. The value of an interoperable Internet is taken to conceptually inform how Internet governance is approached with ideological fragmentation and the power of the lawmakers over the code being seen as more of a danger than the technical fragmentation of the Internet.

It was a wide-ranging panel talk which covered a lot of ground and speakers encouraged attendees to continue the discussion in the main Internet fragmentation sessions on Wednesday.

- Karla White (28 November 2022, 20:00 UTC)

Day 0: The Internet as a commons

"‘The Internet as a commons" session - although under the theme 'Connecting all people and safeguarding human rights' - touched upon issues concerning avoiding Internet fragmentation, a major theme at this year’s IGF.

Recently, attempts have been made to define those parts of the Internet that should be thought of as “commons” for society at large. Laureen van Breen of Wikirate provided a definition of commons - “a land or resource that is belonging to or affecting the whole of a community.” In the past, this might have been pastureland or a water source that served an entire village. This session examined the different aspects of the Internet that could be considered as “commons”, serving communities.

The Internet started off with the underlying concept of sharing. The roots of a decentralised structure lie in the idea of cooperation and common ground. For many years, the openness of the Internet was taken for granted, but recently fragmentation and encroachment are becoming more probable, albeit slightly differing, threats.

From a “commons” perspective, the ubiquity of private services that limit access, state shutdowns, and attempts to limit access pose very real challenges. Both state-based and market-led approaches towards governing the Internet have created tensions, and the idea of the Internet as commons could actually create a useful, sustainable and thriving space to serve communities around the world. Anriette Esterhuysen of the Association for Progressive Communication in South Africa suggested that it would be useful to think of the values and principles that can help us as a global multistakeholder community. She asked how we can use the concept of the commons or the concept of public good and use it as a way of resetting how we think about the Internet.

Some of the discussion touched upon the planned “Global Digital Compact” and how a better framework on the Internet as commons could support these efforts.

Osama Manzar of the Digital Empowerment Foundation also spoke about how states and policy makers need to think about those who cannot currently access the Internet. With half of the world still struggling with connectivity, he asked how the unconnected can be expected to follow online processes, for instance to open a bank account or receive subsidies. What principles of Internet commons could be used to make the Internet affordable and accessible to these communities?

Some of the speakers also addressed the relationship between commons and regulation. The European Union has taken a more regulatory approach towards the Internet, but there are also practical challenges - for example right to data portability. Under EU law, all users have the right to access their data and port it, but the absence of interoperable standards means that in practice this is not possible for many services. Social media platforms are a good example of this, you can’t transfer your profile from one platform to another.

Interoperability is an interesting issue to tackle. Nicolas Echaniz, Altermundi, spoke about the technical issues that the idea of the Internet as commons could address. He used the XMPP protocol for instant messaging as an example. Instant messaging used to be based on XMPP, which meant that users could choose the instant messaging client they wanted to use, and message people using other clients. This was the base technology for Google Messenger and Whatsapp. At some point however, the service providers voluntarily chose to break from an interoperable standard and create systems that are no longer interoperable. It might be worth examining the implications of this kind of technical fragmentation, and how without clear technical agreements, interoperability remains on paper only in certain areas.

The issue of interoperability, who gets to decide on it, whether it remains on paper only, if and how it can be implemented, whether or not it supports innovation – are all knotty questions for the stakeholders at the IGF to continue examining.

- Ulka Athale (28 November 2022, 17:00 UTC)

Day 0: Governance of Digital Infrastructure

Per tradition, GigaNet, the network of academics doing work on Internet governance held their annual symposium during the 0 day of the Global IGF. Their first session focused on digital infrastructure.

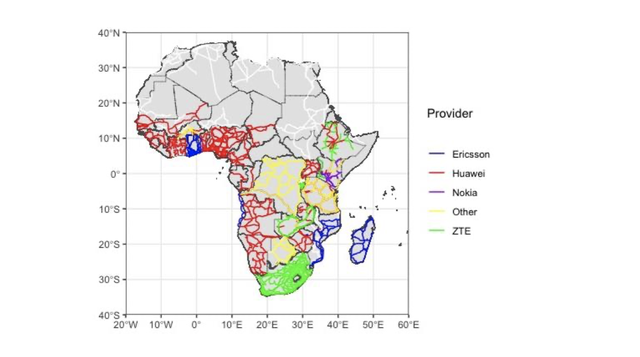

Some years ago the main battles over Internet governance focused on control of core Internet design issues like the domain name system and IP addresses. Now that those matters are largely settled, the battles have moved to other spaces - satellites, AI, standardisation. The first paper by Stephanie Arnold (University of Bologna) eloquently demonstrated another open battlefield of influence between the global superpowers - the digital infrastructure on the African continent.

There are two main things in short supply in Africa - tech giants with the know-how to carry out large infrastructure projects and funding. Large Western aid providers, for example the EU, usually direct funds towards social and environmental programs, leaving the World Bank as one of the few financiers of large-scale infrastructure projects like fiber-optic broadband network construction. Funding from the World Bank is aimed at the most competitive bidder and does not discriminate technology companies based on their origin. Their approach focuses on the formulation of policies and regulations and integrates ICT as a component in its development programs.

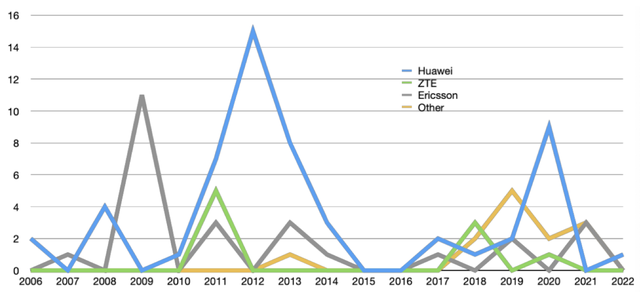

Another big source of funding is China's Digital Silk Road, a sister project of the Belt and Road Initiative. While big tech companies like Huawei and ZTE provide technological know-how, Chinese state entities grant either commercial or concessional loans. In this way China kills several birds with one stone - they enhance their standing in the international political economy, foster their technological clout in developing countries and help their economy cope with overproduction in the infrastructure sector by engaging their companies in projects overseas.

Despite this approach oftentimes ending up being more costly than conventional World Bank funding, it is often the preferred option, since Chinese contenders are able to advance the initial capital cost themselves. Long standing bilateral relations and cross-guaranteed undertakings also play a role. As a result over 70% of fiber optic cables in Africa we realised by Huawei and ZTE.

In another paper, Joanna Kulesza (University of Lodz and former RACI attendee) talked of Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellite constellations which promise to transform connectivity by mitigating the shortcomings of terrestrial networks and satellite communication networks in higher altitudes. The prospect of secure and reliable low-latency broadband has sparked hope, especially in places lacking meaningful connectivity. Such infrastructure however will be owned and operated by private enterprises in a few spacefaring nations. The authors of the paper urge for the need to balance competing interests among a wide range of stakeholders and the need to agree on fundamental governing principles at the international level. They expect that such a governance system would require a mix of national, multi-lateral and multi-stakeholder systems.

In the last paper I have time to mention in this post, Radomir Bolgov and Olga Filatova (Saint Petersburg State University) examine how sanctions affect AI policy development in sanctioned Russia and Iran. They note that sanctions rarely lead to changing of regimes or reducing the level of well-being of elites, but do worsen the lives of ordinary people. The sanctioned state uses the this situation to create an image of the West as an enemy and rallies the people against it.

When it comes to AI, there are two leading technological platforms in the world - the US and Chinese. Russia and Iran need to decide whether to join one of these platforms or build their own, competing with the two already established ones. Sanctions will definitely play a role in the decision.

Russia and Iran are just starting to lay the foundations for the development of AI-related technologies and the testing of AI-based applications. While the paper is very open about the disadvantages in terms of infrastructure, talent and policy facing both countries, they show how national businesses are filling in the vacuum left by the sanctions regime. Both have adopted a number of special documents regulating the development of AI and are encouraging public-private partnerships.

- Gergana Petrova (28 November 2022, 15:00 UTC)

Comments 0

The comments section is closed for articles published more than a year ago. If you'd like to inform us of any issues, please contact us.