On August 25, 2017 Hurricane Harvey made landfall in south Texas, causing widespread property damage, displacing more than 30,000 people, and costing more than 45 lives (as of 2017-09-01). We sympathize with those who were hurt by this disaster, and hope for swift recovery for the region. Here we evaluate what outages in edge networks can say about damage on the ground.

Summary of results

What We See: We were able to see the effects of Hurricane Harvey on the Internet through our Trinocular outage detection system.

We see that landfall was followed by widespread Internet outages in the Corpus Christi area, with 40% or more home networks dropping off the Internet.

We see that over the following days, network outages grew in the Houston area, with many networks dropping off the Internet. However, the fraction of networks lost in Houston was much smaller than in the Corpus Christi area.

Why Does This Matter? Our analysis shows we can observe the results of a hurricane on edge networks of the Internet. Outages in edge networks reflect people’s homes losing utilities and power–therefore we can use the Internet to infer storm damage on people’s lives.

Observations about Internet outages due to storm damages provide unique details about the geographic scope and seriousness of damage. Our inferences can complement other sources of information. News reporters and people on the scene put a human face on how the hurricane affects individuals. But our quantitative measurements of storm damage can help first responders understand where problems are occurring before people call in, and for neighborhoods that have lost communications. Utilities will report on service outages, but during the event they are busy restoring services, so formal reports often follow days later.

Where From Here? We are working to improve our approaches, and we expect to provide near-real time reporting of Internet outages in the coming year.

How Did We Get Here? Our work is supported by the Department of Homeland Security, Science and Technology Directorate, Cyber Security Division through the IMAM (Internet Measurement and Attack Modeling) program (analysis and algorithm development), and the IMPACT (Information Marketplace for Policy and Analysis of Cyber-risk and Trust) program (basic outage data collection and distribution), through a Michael Keston Research Grant at USC/ISI. We are also collaborating with the FCC to evaluate if our work can complement DIRS, to improve assessment of U.S. telecommunications during disasters.

More Details

What did we find?

We recently animated our data showing Hurricane Harvey landfall:

Figure 1: Animation of the effects of hurricane Harvey

Before Landfall

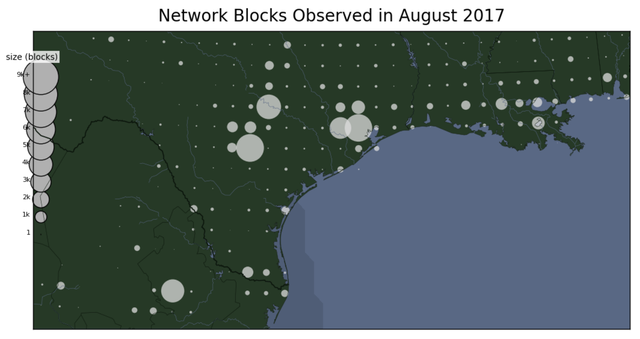

We observe all networks in the world where at least 15 addresses respond to Internet pings (ICMP echo requests). Each network is a block of 256 adjacent IPv4 addresses (addresses 192.0.2.0, 192.0.2.1, up to 192.0.2.255 make up the network 192.0.2.0/24).

In Texas we see thousands of networks, shown below in Figure 2 (note that the scale on this graph is much larger than on the others):

Figure 2: Networks observed in thre region

We see about 9,100 network blocks in the Houston area (the largest circle on the gulf), about 5,000 in San Antonio to the west, about 2,200 in Austin (slightly north), and several hundred each in Laredo and Corpus Christi (towards the southern end of Texas).

To visualize the these networks, we:

- Observe the network with Trinocular, measuring its status every 11 minutes.

- Gather this data to USC/ISI and analyze the data, filtering out noise and blocks that we cannot measure.

- Geolocate each network, mapping its IP addresses to a physical location using Maxmind’s Geolite City database.

- Group these blocks into grid cells by latitude and longitude (here we use grid cells on half-degrees).

- Plot a circle for each grid cell, where

- the area shows how many networks are out in that area at any given time

- the color shows what fraction of networks out in that area Thus big circles show places where many networks are out, and white and red circles show places where most of the networks are out.

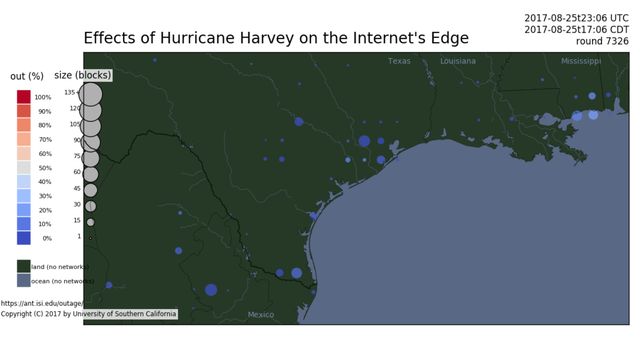

Before Hurricane Harvey makes landfall we see a few outages (small circles are visible), but they are only a tiny fraction of all the networks in Texas (the circles are all dark blue).

Figure 3: Networks just before Hurricane Harvey made landfall

Shortly after landfall

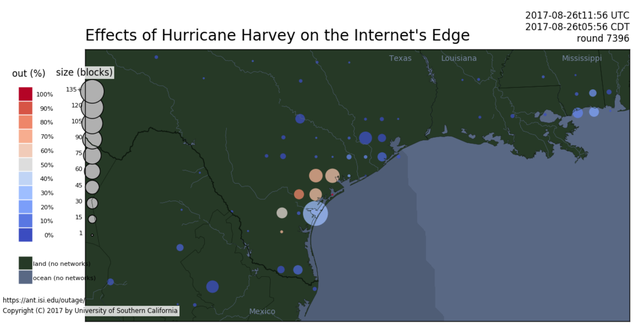

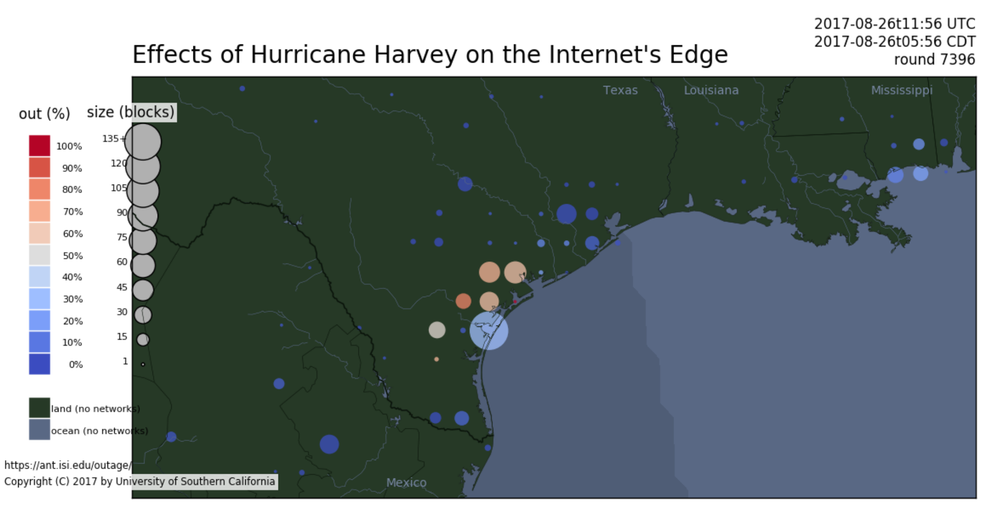

Hurricane Harvey made landfall at 2017-08-26t03:00Z (August 25, 10pm CDT) near Corpus Christi, Texas. Although a Category 4 hurricane at landfall with high winds, we only begin to see Internet outages around daybreak (2017-08-26t11:56Z, just before 7am CDT August 26, round 7,396):

Figure 3: Networks shortly after the Hurricane Harvey made landfall

Comparing this visualization to what we saw the day before, we see:

- Many new network outages in the Corpus Christi area - the larger circles in the center of this map.

- More concerning, we see that a large fraction of networks are out right at the location of landfall - the white circles suggest 50% of the edge networks are out.

Two days later

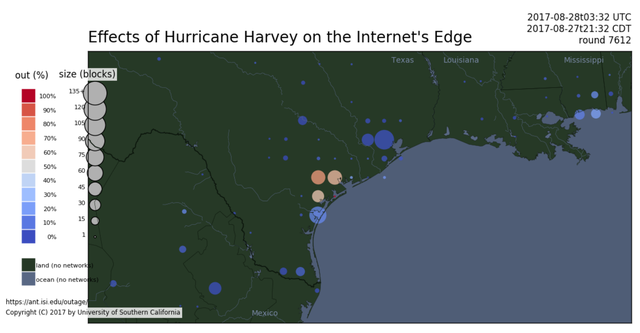

Serious effects of Hurricane Harvey continued over the next several days, as it became a tropical storm and left more than a meter of rain on the Houston area (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Network outages two days after the landfall

This visualization of 2017-08-28t03:32 (August 27, 10:30pm CDT) shows:

- Outages north of Corpus Christi remain pervasive - the white circles suggest about 50% of blocks remain out.

- But some improvements are beginning - these circles are slightly smaller than two days before.

- We begin to see problems in the Houston area - the a large blue circle further up the coast has grown in size.

- While problems in Houston affect many networks (it’s a big city with many networks - the circle is large), but the majority of networks are operational (the circle is dark blue, not white or red).

Things we do not see

A few caveats about our work:

-

We are studying Internet edge networks, not the backbone networks. Our understanding is that the core Internet routing did well during Hurricane Harvey. The core Internet is very reliable, with multiple paths connecting telecommunications facilities with backup power and storm hardening. Edge networks are more vulnerable, since they usually have one physical connection to the Internet and one source of power, both by wires into a house.

-

We study edge networks, not individual computers. We don’t know who uses individual IP addresses (and we don’t want to know), and in many ISPs, the association of individuals with IP addresses change over time.

-

Currently we are processing data quarterly and on demand, not continuously. We did special processing for this event. We are working towards near-real-time reporting of network outages, but that work is still progressing and is not yet complete.

What are we doing to improve our understanding?

We have been studying network outages since 2011.

Research and Peer-Review: Our Trinocular outage detection system is the only peer-reviewed (DOI), active outage detection system that is able to continuously evaluate outages in millions of edge networks around the globe. It complements prior work in detecting routing outages (for example, Hubble in NSDI 2008, or LIFEGUARD in SIGCOMM 2012), weather-triggered Internet outages, and passive observations of network outages.

Data: We release all data collected through Trinocular through the DHS IMPACT program—please see our outages dataset page, all our datasets, and the IMPACT portal for information about obtaining this data.

The dataset including Hurricane Harvey will be internet_outage_adaptive_a29all-20170702 and will be released in October 2017. Until the full data is released, we have a preliminary dataset through August 2017 available on request.

The data provided here ends on 2017-08-29t11:15Z; we have additional data and hope to process it soon.

Broader Efforts: Our work is supported by the Department of Homeland Security, Science and Technology Directorate, Cyber Security Division through the IMAM (Internet Measurement and Attack Modeling) program (analysis and algorithm development), and the IMPACT (Information Marketplace for Policy and Analysis of Cyber-risk and Trust) program (basic outage data collection and distribution), through a Michael Keston Research Grant at USC/ISI.

We are also collaborating with the FCC to evaluate if our work can complement DIRS, to improve assessment of U.S. telecommunications during disasters.

DHS has solicited input on a new program, PARADINE with the goal of supporting research that will assess Disruptive Internet-scale Network Events.

This analysis and data collection was done by John Heidemann and Yuri Pradkin of USC’s Information Sciences Institute.

This page is a copy from our Harvey page at USC/ISI. Please see there for pointers to other work and updated data.

Comments 0

The comments section is closed for articles published more than a year ago. If you'd like to inform us of any issues, please contact us.