Much has been said in recent weeks about various forms of cyber spying. The United States has accused the Chinese of cyber espionage and stealing industrial secrets. A former contractor to the United States’ NSA, Edward Snowden, has accused various US intelligence agencies of systematic examination of activity on various popular social network services, through a program called “PRISM”. These days cloud services may be all the vogue, but there is also an emerging understanding that once your data heads into one of these clouds, then it’s no longer necessarily entirely your data; it may have become somebody else’s data too.

And the rules and protocols relating to third party access to what used to be your data is no longer necessarily the rules and protocols as defined by your country’s legislative and regulatory framework. Other rules and protocols that are used in other countries may apply for third party access to what used to be your data. And perhaps if you are not a citizen of this other country you may have few, if any, rights regarding the privacy of this data, or any rights regarding the secure handling of personally identifying information in this foreign regime.

Obviously, all of this has caused much public debate. For various intelligence agencies the Internet represents what they claim is an essential source of valuable information. This information, they say, is vital to their work of protecting the security and safety of the citizens of their country. For others this information gathering activity represents an abuse of privilege and power, as the more traditional process of judicial oversight and various checks and balances in executing warrants to eavesdrop on individual’s activities appear to have been discarded in what looks to be an undisciplined rush to exploit this rich vein of online information.

Doubtless, this is a debate that will continue for many years to come, as finding the appropriate balance between these often conflicting interests is never an easy task. However, much of this public debate is carried out with a scarcity of information. How is this online snooping carried out? Who is looking at whom? Can we see this digital snooping happen?

We saw an inadvertent instance of this form of online snooping when, in June 2012, a major Australian carrier, Telstra, appeared to breach the provisions of national legislation when they apparently configured equipment in their mobile data network that intercepted customer’s web fetches and sent a copy of these URLs to a third party located in the United States. Telstra gave every appearance of being unconcerned about this when they called such digital stalking “a normal network operation,” while others appeared to be very concerned about the abuse of the carrier’s role in performing such unauthorized eavesdropping on customers’ traffic (see the July’12 ISP Column for my perspective on this incident).

A year later, and with allegations of various forms of cyber spying flying about, it’s probably useful to ask some more questions. What is a reasonable expectation about privacy and the Internet? Should we now consider various forms of digital stalking to be “normal”? To what extent can we see information relating to individuals’ activities online being passed to others?

That last one is an interesting question, and in particular it’s a question where we might be able to provide a small amount of data about such trafficking of information.

In our efforts to measure the extent of deployment of IPv6 and DNSSEC we present URLs to some 800,000 users each day, and we use the online ad delivery networks to try and ensure that these users are drawn in a relatively random fashion from across the entire Internet. All these URLs refer back to our server, and as each generated URL includes unique components within the DNS name part, we would expect to see at the server that each unique URL is used just once, and by one unique client. After all, it’s a common expectation on the part of many Internet users that the web sites that your system contacts is essentially private information, so when you visit a web site using a unique URL, you would not conventionally expect a third party to eavesdrop on the session and capture this URL.

If this was truly the case, then each URL that we hand out to clients as part of our measurement program would be used once, and only once, and only by the client that received the URL. And most of the time that’s exactly what we do see. But at times we see that the same unique URL is being used more than once. What can we understand from these cases? Are we seeing evidence of various forms of digital stalking?

Let’s review some data sets and see what we can find.

In the period 1 May 2013 through to 18 June 2013 we presented some 29,171,864 unique URLs to clients. Most of these URLs were presented to the server from a single client IP address, as we would expect, but over this period some 612,089 URLs were presented to us more than once, from different client IP addresses. In some form or fashion the original fetch of the set of URLs from a client’s IP address was subsequently duplicated using a different IP address. That’s some 2.1% of all URLs, which, if this truly is an indicator of the level of digital stalking in todays Internet, then it’s a disturbingly high figure.

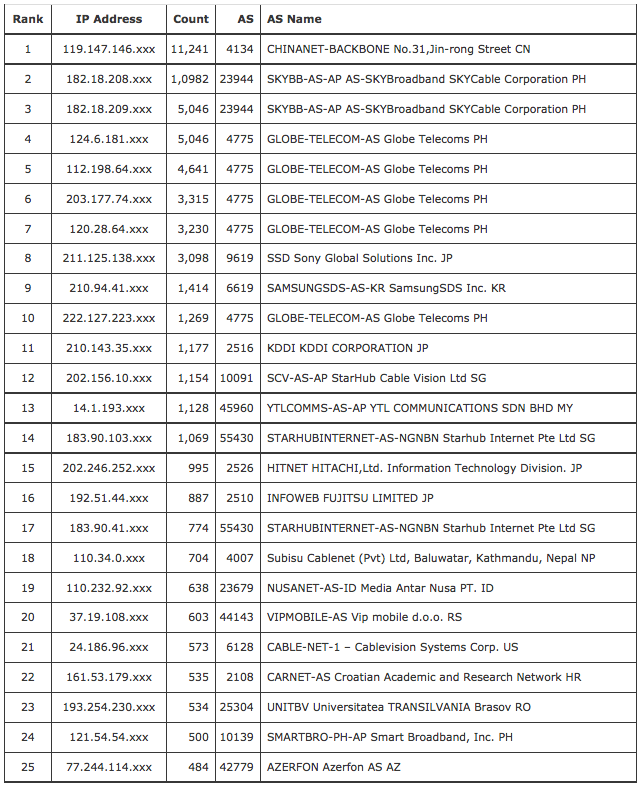

What addresses are performing this form of tracking of client activity?

Here’s the top 25 IP addresses where were observed to be performing this URL re-fetch.

| Rank | IP Address | Count | AS | AS Name |

| 1 | 119.147.146.xxx | 11,241 | 4134 | CHINANET-BACKBONE No.31,Jin-rong Street CN |

| 2 | 182.18.208.xxx | 1,0982 | 23944 | SKYBB-AS-AP AS-SKYBroadband SKYCable Corporation PH |

| 3 | 182.18.209.xxx | 5,046 | 23944 | SKYBB-AS-AP AS-SKYBroadband SKYCable Corporation PH |

| 4 | 124.6.181.xxx | 5,046 | 4775 | GLOBE-TELECOM-AS Globe Telecoms PH |

| 5 | 112.198.64.xxx | 4,641 | 4775 | GLOBE-TELECOM-AS Globe Telecoms PH |

| 6 | 203.177.74.xxx | 3,315 | 4775 | GLOBE-TELECOM-AS Globe Telecoms PH |

| 7 | 120.28.64.xxx | 3,230 | 4775 | GLOBE-TELECOM-AS Globe Telecoms PH |

| 8 | 211.125.138.xxx | 3,098 | 9619 | SSD Sony Global Solutions Inc. JP |

| 9 | 210.94.41.xxx | 1,414 | 6619 | SAMSUNGSDS-AS-KR SamsungSDS Inc. KR |

| 10 | 222.127.223.xxx | 1,269 | 4775 | GLOBE-TELECOM-AS Globe Telecoms PH |

| 11 | 210.143.35.xxx | 1,177 | 2516 | KDDI KDDI CORPORATION JP |

| 12 | 202.156.10.xxx | 1,154 | 10091 | SCV-AS-AP StarHub Cable Vision Ltd SG |

| 13 | 14.1.193.xxx | 1,128 | 45960 | YTLCOMMS-AS-AP YTL COMMUNICATIONS SDN BHD MY |

| 14 | 183.90.103.xxx | 1,069 | 55430 | STARHUBINTERNET-AS-NGNBN Starhub Internet Pte Ltd SG |

| 15 | 202.246.252.xxx | 995 | 2526 | HITNET HITACHI,Ltd. Information Technology Division. JP |

| 16 | 192.51.44.xxx | 887 | 2510 | INFOWEB FUJITSU LIMITED JP |

| 17 | 183.90.41.xxx | 774 | 55430 | STARHUBINTERNET-AS-NGNBN Starhub Internet Pte Ltd SG |

| 18 | 110.34.0.xxx | 704 | 4007 | Subisu Cablenet (Pvt) Ltd, Baluwatar, Kathmandu, Nepal NP |

| 19 | 110.232.92.xxx | 638 | 23679 | NUSANET-AS-ID Media Antar Nusa PT. ID |

| 20 | 37.19.108.xxx | 603 | 44143 | VIPMOBILE-AS Vip mobile d.o.o. RS |

| 21 | 24.186.96.xxx | 573 | 6128 | CABLE-NET-1 – Cablevision Systems Corp. US |

| 22 | 161.53.179.xxx | 535 | 2108 | CARNET-AS Croatian Academic and Research Network HR |

| 23 | 193.254.230.xxx | 534 | 25304 | UNITBV Universitatea TRANSILVANIA Brasov RO |

| 24 | 121.54.54.xxx | 500 | 10139 | SMARTBRO-PH-AP Smart Broadband, Inc. PH |

| 25 | 77.244.114.xxx | 484 | 42779 | AZERFON Azerfon AS AZ |

There is, however, an important consideration here. While it’s common to see web proxies behave in a mode that is not readily detectable, we also see web proxies that appear to operate in a mode that is quite overt, where the proxy server appears to be given a feed of the URLs used by the community of users served by the proxy server and the proxy server separately queries the URL’s server to fetch its own copy of the web object. Web proxies are very commonly deployed as a means of improving the cost efficiency of networks. What the proxy attempts to do is to reduce the extent of duplicate fetches of information to the client community that is served by the proxy. Not only does the network operator see some efficiencies in terms of reduction in total traffic loads presented to upstream transits, but also the users behind the proxy often see a much faster download time for proxy-served web objects. So the prevalence of the use of web proxies in various developing economies in this table should not come as any particular surprise.

Can we filter out what we assume to be the web proxies out of this data? One observation is that it is quite common to see the web proxy residing in the same Autonomous System as the client who is served by the web proxy. So what if we filter out all data where the original IP address and the shadow IP address are in the same originating AS? What does the table look like then?

| Rank | IP Address | Count | AS | AS Name |

| 1 | 119.147.146.xxx | 8,886 | 4134 | CHINANET-BACKBONE No.31,Jin-rong Street CN |

| 2 | 220.181.158.xxx | 493 | 23724 | CHINANET-IDC-BJ IDC, China Telecommunications Corporation CN |

| 3 | 123.125.161.xxx | 446 | 4808 | CHINA169-BJ CNCGROUP IP China169 Beijing Province Network CN |

| 4 | 210.133.104.xxx | 285 | 7677 | DNP Dai Nippon Printing Co., Ltd JP |

| 5 | 202.214.150.xxx | 266 | 2497 | IIJ Internet Initiative Japan Inc. JP |

| 6 | 112.65.211.xxx | 248 | 17621 | CNCGROUP-SH China Unicom Shanghai network CN |

| 7 | 221.176.4.xxx | 226 | 9808 | CMNET-GD Guangdong Mobile Communication Co.Ltd. CN |

| 8 | 62.84.94.xxx | 204 | 16130 | FiberLink Networks LB |

| 9 | 212.40.141.xxx | 203 | 31126 | SODETEL-AS SODETEL SAL LB |

| 10 | 101.69.163.xxx | 163 | 4837 | CHINA169-BACKBONE CNCGROUP China169 Backbone CN |

| 11 | 59.162.23.xxx | 158 | 4755 | TATACOMM-AS TATA Communications IN |

| 12 | 8.35.201.xxx | 156 | 15169 | GOOGLE – Google Inc. US |

| 13 | 118.186.36.xxx | 149 | 23724 | CHINANET-IDC-BJ IDC, China Telecommunications Corporation CN |

| 14 | 190.96.112.xxx | 147 | 262150 | Empresa Provincial de Energia de Cordoba AR |

| 15 | 202.155.113.xxx | 143 | 4795 | INDOSATM2-ID INDOSATM2 ASN ID |

| 16 | 118.228.151.xxx | 142 | 4538 | ERX-CERNET-BKB China Education and Research Network Center CN |

| 17 | 123.125.73.xxx | 136 | 4808 | CHINA169-BJ CNCGROUP IP China169 Beijing Province Network CN |

| 18 | 69.41.14.xxx | 133 | 47018 | CE-BGPAC – Covenant Eyes, Inc. US |

| 19 | 118.97.198.xxx | 131 | 17974 | TELKOMNET-AS2-AP PT Telekomunikasi Indonesia ID |

| 20 | 112.215.11.xxx | 128 | 17885 | JKTXLNET-AS-AP PT Excelcomindo Pratama ID |

| 21 | 122.2.0.xxx | 125 | 9299 | IPG-AS-AP Philippine Long Distance Telephone Company PH |

| 22 | 176.28.78.xxx | 123 | 197893 | ELSUHD-AS Elsuhd Net Ltd. Communications and Computer Services IQ |

| 23 | 14.139.97.xxx | 120 | 55824 | RSMANI-NKN-AS-AP National Knowledge Network IN |

| 24 | 211.155.120.xxx | 116 | 23724 | CHINANET-IDC-BJ IDC, China Telecommunications Corporation CN |

| 25 | 121.96.61.xxx | 114 | 6648 | BAYAN Bayan Telecommunications, Inc. PH |

This has reduced the counts considerably, which supports the view that the predominant reason why we see duplicated URL fetches is a certain form of web proxy operation where the proxy server performs an independent fetch of the web object. When we filter out the instances of duplicated URL fetches where the original and the duplicate fetch IP addresses come from the same network (the same originating Autonomous System) the what is left appears to be systems located in China (10 of the top 25 are located in China), Japan, Lebanon, India, Indonesia, Iraq, Argentina, the United States and the Philippines.

It is still feasible that these are proxy web servers, performing the proxy function for “downstream” networks. However, we also see a slightly different motivation for URL tracking in this list. On this list is a web filtering service located in the United States, Convenant Eyes (http://www.covenanteyes.com), where the intended functionality is that a feed of all URLs visited in a client system is sent “in an easy-to-read report to someone you trust,” to quote their web site. It appears that the system also fetches these URLs as part of the reporting service.

The next filter I’ll use on this list is to use the country of origin, and filter out all those instances where the client and the duplicate fetch system use IP addresses that are located in the same country. The resultant list is that of a set of servers who fetch a URL that was already fetched by a client, and where the client and this duplicate fetch server appear to be located in different countries.

| Rank | IP Address | Count | AS | AS Name |

| 1 | 119.147.146.xxx | 7,001 | 4134 | CHINANET-BACKBONE No.31,Jin-rong Street CN |

| 2 | 8.35.201.xxx | 156 | 15169 | GOOGLE – Google Inc. US |

| 3 | 190.216.130.xxx | 84 | 3549 | GBLX Global Crossing Ltd. AR |

| 4 | 190.27.253.xxx | 82 | 19429 | ETB – Colombia CO |

| 5 | 61.92.16.xxx | 62 | 9269 | HKBN-AS-AP Hong Kong Broadband Network Ltd. HK |

| 6 | 208.80.194.xxx | 53 | 13448 | WEBSENSE Websense, Inc. US |

| 7 | 112.140.187.xxx | 33 | 45634 | SPARKSTATION-SG-AP 10 Science Park Road SG |

| 8 | 69.41.14.xxx | 32 | 47018 | CE-BGPAC – Covenant Eyes, Inc. US |

| 9 | 126.117.225.xxx | 31 | 17676 | GIGAINFRA Softbank BB Corp. JP |

| 10 | 113.43.175.xxx | 29 | 17506 | UCOM UCOM Corp. JP |

| 11 | 202.249.25.xxx | 26 | 4717 | AI3 WIDE Project JP |

| 12 | 139.193.204.xxx | 25 | 23700 | BM-AS-ID PT. Broadband Multimedia, Tbk ID |

| 13 | 180.13.45.xxx | 22 | 4713 | OCN NTT Communications Corporation JP |

| 14 | 201.221.124.xxx | 21 | 27989 | BANCOLOMBIA S.A CO |

| 15 | 123.125.161.xxx | 21 | 4808 | CHINA169-BJ CNCGROUP China169 Beijing Province Network CN |

| 16 | 220.181.158.xxx | 17 | 23724 | CHINANET-IDC-BJ IDC, China Telecommunications Corporation CN |

| 17 | 208.184.77.xxx | 17 | 6461 | MFNX MFN – Metromedia Fiber Network US |

| 18 | 183.179.254.xxx | 16 | 9269 | HKBN-AS-AP Hong Kong Broadband Network Ltd. HK |

| 19 | 203.192.154.xxx | 16 | 10026 | PACNET Pacnet Global Ltd JP |

| 20 | 139.193.223.xxx | 13 | 23700 | BM-AS-ID PT. Broadband Multimedia, Tbk ID |

| 21 | 175.134.140.xxx | 12 | 2516 | KDDI KDDI CORPORATION JP |

| 22 | 210.187.58.xxx | 12 | 4788 | TMNET-AS-AP TM Net, Internet Service Provider MY |

| 23 | 195.93.102.xxx | 12 | 1668 | AOL-ATDN – AOL Transit Data Network GB |

| 24 | 221.82.58.xxx | 12 | 17676 | GIGAINFRA Softbank BB Corp. JP |

| 25 | 167.205.22.xxx | 12 | 4796 | BANDUNG-NET-AS-AP Institute of Technology Bandung ID |

That first entry is quite exceptional. In the 49 day data collection window we saw some 7,000 instances of this duplicate URL fetch, while the second highest count was far lower, at 156 instances.

Lets take a closer look at the actions of the 119.147.146.xxx system. In what countries were the original clients located? (As the system is located in China, I’ll add back in the counts of clients also located in China in this list.)

Rank

| Count | Country | |

| AE | 27 | United Arab Emirates |

| AG | 2 | Antigua and Barbuda |

| AL | 32 | Albania |

| AM | 13 | Armenia |

| AR | 19 | Argentina |

| AT | 5 | Austria |

| AU | 21 | Australia |

| AW | 6 | Aruba |

| AZ | 8 | Azerbaijan |

| BA | 27 | Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| BD | 1 | Bangladesh |

| BE | 10 | Belgium |

| BG | 45 | Bulgaria |

| BN | 1 | Brunei Darussalam |

| BO | 1 | Bolivia |

| BR | 44 | Brazil |

| BS | 1 | Bahamas |

| BY | 7 | Belarus |

| BZ | 4 | Belize |

| CA | 125 | Canada |

| CL | 13 | Chile |

| CN | 4,622 | China |

| CO | 11 | Colombia |

| CR | 1 | Costa Rica |

| CW | 2 | Curaçao |

| CY | 1 | Cyprus |

| CZ | 37 | Czech Republic |

| DE | 21 | Germany |

| DO | 2 | Dominican Republic |

| DZ | 19 | Algeria |

| EC | 8 | Ecuador |

| EG | 22 | Egypt |

| ES | 38 | Spain |

| FR | 68 | France |

| GB | 45 | United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland |

| GE | 12 | Georgia |

| GR | 25 | Greece |

| GY | 1 | Guyana |

| HK | 721 | Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of China |

| HN | 1 | Honduras |

| HR | 9 | Croatia |

| HU | 67 | Hungary |

| ID | 159 | Indonesia |

| IE | 16 | Ireland |

| IL | 8 | Israel |

| IN | 32 | India |

| IQ | 21 | Iraq |

| IT | 52 | Italy |

| JM | 5 | Jamaica |

| JO | 2 | Jordan |

| JP | 2,910 | Japan |

| KE | 1 | Kenya |

| KG | 1 | Kyrgyzstan |

| KH | 28 | Cambodia |

| KR | 27 | Republic of Korea |

| KW | 1 | Kuwait |

| KZ | 11 | Kazakhstan |

| LA | 6 | Lao People’s Democratic Republic |

| LK | 11 | Sri Lanka |

| LT | 12 | Lithuania |

| LV | 6 | Latvia |

| MA | 6 | Morocco |

| MD | 2 | Republic of Moldova |

| ME | 7 | Montenegro |

| MK | 69 | The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia |

| MM | 2 | Myanmar |

| MN | 36 | Mongolia |

| MO | 37 | Macao Special Administrative Region of China |

| MP | 4 | Northern Mariana Islands |

| MT | 4 | Malta |

| MU | 7 | Mauritius |

| MX | 107 | Mexico |

| MY | 375 | Malaysia |

| NC | 1 | New Caledonia |

| NI | 1 | Nicaragua |

| NL | 15 | Netherlands |

| NO | 8 | Norway |

| NP | 1 | Nepal |

| NZ | 20 | New Zealand |

| OM | 1 | Oman |

| PA | 11 | Panama |

| PE | 29 | Peru |

| PH | 166 | Philippines |

| PK | 1 | Pakistan |

| PL | 340 | Poland |

| PR | 7 | Puerto Rico |

| PS | 9 | Occupied Palestinian Territory |

| PT | 1 | Portugal |

| RO | 197 | Romania |

| RS | 62 | Serbia |

| RU | 32 | Russian Federation |

| RW | 1 | Rwanda |

| SA | 24 | Saudi Arabia |

| SE | 3 | Sweden |

| SG | 83 | Singapore |

| SI | 13 | Slovenia |

| SK | 13 | Slovakia |

| SR | 2 | Suriname |

| SV | 3 | El Salvador |

| TH | 138 | Thailand |

| TN | 3 | Tunisia |

| TR | 57 | Turkey |

| TW | 1,241 | Taiwan |

| UA | 37 | Ukraine |

| US | 371 | United States of America |

| UZ | 1 | Uzbekistan |

| VC | 1 | Saint Vincent and the Grenadines |

| VE | 16 | Venezuela |

| VN | 249 | Vietnam |

| YE | 1 | Yemen |

That’s an impressive list of original clients whose URL fetches were duplicated by this system. The list spans 110 different countries, with high counts in Japan and Taiwan. I would be somewhat surprised if I were to learn that the system that uses the IP address 119.147.146.xxx is a conventional web proxy system, but at the same time it is hard to believe that this would be part of any covert operation to gather data. The use of a consistent IP address to perform these fetches points to a poor effort to conceal its function, if there was any effort to hide its existence at all, and this overt presence supports a more benign explanation of its role. Perhaps this system uses a highly distributed set of web proxies to feed it URLs, which it then examines as part of a function of feeding a web search or web filter product with unique URLs. However, it is somewhat of a challenge to understand how this setup is able to pull URLs from across the entire Internet. Other possible explanations, such as a bot system, or some other form of coerced data collection are feasible, but, in the absence of any serious pointers to malicious activity, a relatively benign motivation is the most likely candidate here.

In relation to the scale of the entire Internet, our analysis of some 30 million web fetches across a 49 day period represents a microscopic proportion of the Internet’s activity. However, the ability to detect anomalous behaviour within this microcosm of web activity is perhaps illustrative of what we should expect on the broader Internet. While this small data set does not show any clear evidence of consistent digital stalking or cyber snooping of any form, it does illustrate one extremely important maxim for the Internet – nothing on the Internet is completely private. Even when encryption can, to some extent, provide some privacy protection on the content of conversations and transactions on the Internet, you should always bear in mind that the sites you go to, and when you go to them, form part of a readily accessible pool of data that is not private. And it should not come as a surprise to learn that there are systematic efforts underway on the Internet to collect this data about your online behaviour and interpret and use it in various ways.

So it’s highly likely that from time to time, or even more often than that, on the Internet someone is indeed looking right at you.

In the classic film Casablanca, Rick’s toast to Ilsa, “Here’s looking at you, kid”, used several times, is not in the draft screenplays, but has been attributed to something Humphrey Bogart said to Ingrid Bergman as he taught her poker between takes. It was voted the 5th most memorable line in cinema in AFI’s 100 Years…100 Movie Quotes by the American Film Institute.

Six lines from Casablanca appeared in the AFI list, the most of any film. The other five are:

”Louis, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.”

”Play it, Sam. Play ‘As Time Goes By’.”

”Round up the usual suspects.”

”We’ll always have Paris.”

”Of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine.”

[Wikipedia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Casablanca_(film)

]

This article has originally been published on the APNIC Blog .

Comments 4

The comments section is closed for articles published more than a year ago. If you'd like to inform us of any issues, please contact us.

Tassos •

Do you think it would be possible to initially (before taking into consideration same AS and country) filter well-known (mostly anonymous) proxies? http://hidemyass.com/proxy-list/ could provide such a list.

Geoff Huston •

Thanks for the great suggestion Tassos - I was unaware that such a list even existed!

Adrian •

Interesting stuff! Possibly some kind of chinese browser toolbar passing viewed URLs back to an indexer? Seems like the countries with a high number of hits are geographically close to China. Baidu toolbar or something similar maybe?

Geoff Huston •

That is a plausible suggestion as to the cause of this. What struck me about this was that there was a wide range of countries, but with the exception of the Chain, Taiwan, Japan, and Hong Kong group of countries, the "stalking rate" appeared to be independent of the number of Internet users in each of those countries. It's as if the system, whatever it is, is choosing to fetch URLs from a wide a range of countries as possible. It certainly _could_ be a plug in or tool bar, Equally it _could_ be the outcome of some form of virus or bot system that is feeing a stream of URLs back to a control point.