Why did a network technology such as the Internet, designed to pass control away from the central network to the connected devices, succumb to the level of centrality we see today? In this guest post, Geoff Huston shares his thoughts on the topic of centrality.

The IRTF is a research-oriented part of the larger IETF structure. It has several research groups. One of which, DINRG, is looking at decentralised Internet infrastructure.

That’s a big topic. You could certainly look at distributed decentralised blockchain frameworks applied to ledgers, used by Bitcoin and similar, or self-organising systems that perform orchestration without imposed control, or distributed hash tables. The DINRG research group has certainly looked at this, and more, over the past few years. However, much can also be learned from looking at the opposite of decentralised systems and raising our view from individual components to the entire industry. To what extent is the Internet now centralised?

It certainly seems that the Internet is now the realm of a small number of enterprises that dominate this space. This is no longer a diverse and vibrant environment where new entrants compete on equal terms with incumbents, where the pace of innovation and change is relentless, and users benefit from having affordable access to an incredibly rich environment of goods and services that is continually evolving.

Instead, today’s Internet appears to be reliving the telco nightmare where a small clique of massive incumbent operators imposes overarching control on the entire service domain, repressing any form of competition, and innovation, and extracting large profits from their central role. The only difference between today and the world of the 1970s is that in the telco era these industry giants had a national footprint, but now their dominance is expressed globally.

How did we get here? Why did a network technology such as the Internet, which was designed to pass control away from the central network to the connected devices, succumb to the same level of centrality?

Those questions were the topic of the most recent meeting of the DINRG (held online, of course, in these COVID-cursed times).

What follows are my thoughts on this topic of centrality. You can find my presentation slides, which examines the larger issues of market dominance using an historical perspective here.

It’s Just Economics

In traditional public economics, one of the roles of the public sector is to detect, and presumably rectify, situations where the conventional operation of a market has failed. Of course, a related concern is not just the failure of the efficient operation of a market, but the situation where the market collapses and simply ceases to exist.

In an economy that is largely led by private sector activity, the health of the economy is highly dependent on the efficient operation of such markets. Inefficient markets or distorted markets act as an impost on the economy, imposing hidden costs on market actors and deterring further private sector capital investment.

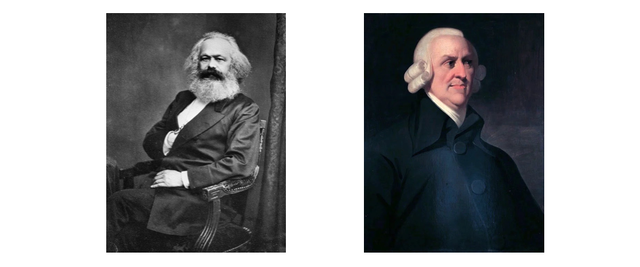

In such a light, markets are more than mere enablers of simple transactions between a buyer and a seller. Karl Marx was one of the first economists to think about the market economy as a global entity, and its fundamental role as an arbiter of resource allocation in society. When we take this view, and start looking for potential failure points, one of the signs is ‘choke points’, where real investment levels fall. Such failures are often masked by a patently obvious masquerade of non-truths taking the place of data and facts. Any study of an economy involves understanding the nature of these choke points. Telecommunication services are not an isolated case but can be seen as just another instance of a choke point in the larger economy. Failure to keep common communications services functioning efficiently and effectively can have implications across many other areas of economic activity.

What defines an ‘efficient’ market? From the perspective of Adam Smith, the precondition is unconstrained consumers (who can purchase goods from any provider), replaceable providers of the goods or service being traded, open pricing information, and open access to the marketplace. Consumers will be motivated to buy goods from the producer that brings products to market at the lowest price. Producers will then be motivated to seek the most efficient form of production of goods to sustain a competitive market price. However, that is by no means the final word here and the Nobel Prize winning efforts of Eguene Fama in 1970 are also relevant to the question of whether an ‘efficient’ market is one where market prices reflect all available relevant information at the time.

A continuing source of pressure on markets is that of innovation. New products and services can stimulate greater consumer spending or realise greater efficiencies in the production of the service. Either outcome can lead to the opportunity of greater revenues for the enterprise. The assumption here, of course, is that innovation is unconstrained and market incumbents cannot define the scope or accessibility of further innovations in the market.

Internet Innovation

Innovation within the Internet occurs in many ways, from changes in the components of a device through to changes in the network platform itself and deployment of applications. We’ve seen all of these occur in rapid succession in the brief history of the Internet, from the switch to mobility, the deployment of broadband access infrastructure, the emerging picture of so-called ‘smart cities’, and of course, the digitisation of production and distribution networks in the new wave of retailing enterprises. We’ve seen the evolution of platforms from megalithic ‘mainframes’ to deeply embedded processors, and the evolution of the locus of control and orchestration from the network through to device platforms through to the individual applications themselves.

Much of this innovation is an open process that operates without much deliberate direction or deterministic predictability. Governance of the overall process of innovation and evolution cannot concentrate on the innovative mechanism intrinsically, but, by necessity, needs to foster the process through the support of the underlying institutional processes of research and prototyping.

Through much of the twentieth century the conventional wisdom was that public funding through direct support of basic research was the only way to overcome prohibitively high transaction and adaptation costs in exploring innovative opportunities. However, behind this lies an assumption that the public sector has a higher risk appetite and a larger capital volume than individual private sector actors.

The transformation of wealth and capital markets in the latter part of the twentieth century has changed all this. For example, with a current market capitalisation of USD 2 trillion, Apple has a higher ‘worth’ than all except eight of the world’s national economies, as measured by national GDP. This has an impact on who has the capital and appetite to engage in high-risk ventures in innovation.

However, the interests of the private and public sector are fundamentally different, and while the public sector has strong motivation for innovation as an open activity whose results are accessible to all, the private sector tends to view their investments in innovation in a more proprietorial way. When innovation is managed in such a way through the private sector it no longer has the same ability to bring competitive pressure to bear on markets. In fact, it often tends to work in the opposite manner by further entrenching the position of market incumbents through their exclusive access to innovation in production.

Size and Centrality

Business transformation is often challenging. What we have today within the Internet, with the rise of content and cloud providers into dominant positions in this industry, is a more complex transformational environment that is largely opaque to external observers. What matters for consumers is their service experience, and that increasingly depends on what happens inside these content distribution clouds. As these content data network operators terminate their private distribution networks closer to the customer edge, the role of the traditional carriage service providers (which used to provide the connection between services and customers) is shrinking. But as their role shrinks then we also need to bear in mind that these carriage networks were the historical focal point of monitoring, measurement, and regulation. As their role shrinks, so does our visibility into this digital service environment.

It is a significant challenge to understand this content economy. What services are being used? What connections are being facilitated? What profile of content traffic are they generating? Just how valuable is this activity? If we can’t directly observe these activities, then the question as to the value of these activities, and the extent to which these markets are openly competitive, become more challenging to answer. In the absence of effective competition markets tend to consolidate and succumb to monopolisation and centralisation. ‘Big’ often becomes the defining characteristic of such markets. This poses a venerable economic topic: is big necessarily bad?

Elephants in the Room

There is little doubt that today’s digital environment is dominated by a small number of very big enterprises. The list of the largest public companies, as determined by market capitalisation, includes the US enterprises Apple, Alphabet, Amazon, Facebook, Microsoft and Facebook, and the Chinese enterprises Alibaba and Tencent. Admittedly, there are other measurements of size that include metrics of revenues, profits, customers, and the scope and impact of a corporate enterprise, but the considerable market capitalisation of these seven companies place them in the global top ten, which makes them outstandingly big.

But are they necessarily bad? Does the combination of their unprecedented size and clear market dominance lead to business practices that are exploitative of their workforce? Or practices that are exploitative of their consumers? Or behaviours that are corrupt or collusive? Perhaps their size leads to a point of economic fragility where, were these enterprises to fail, other parts of our economy would fail as well, and we would be confronted with yet another major economic crisis with its attendant societal impact? The global financial crisis of 2008 has explored the concept of ‘too big to fail’ in the financial world. Do we have a similar situation with some, or all, of these digital service enterprises?

A Brief Historical Perspective

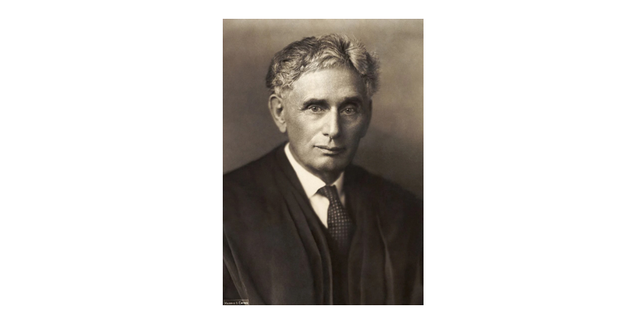

At the start of the twentieth century a member of the US Supreme Court, Louis Brandeis, argued that big business was too big to be managed effectively in all cases. He argued that the growth of these very large enterprises were at the extreme end of the excesses of monopolies, and their behaviours harmed competition, harmed customers, and harmed further innovation. He observed that the quality of their products tended to decline, and the prices of their products tended to rise. When large companies can shape their regulatory environment to leverage lax regulatory oversight to take on more risk than they can manage and transfer downside losses onto the taxpayer, we should all be very concerned.

It is hard to disagree with Brandeis. If this outcome is an inevitable consequence of simply being big, and given the experiences of the 2008/2009 financial meltdown, we could even conclude that Brandeis’ observations apply to the financial sector. But do these systemic abuses of public trust in the financial sector translate to concerns related to the Internet and the broader aspect of the emergence of the so-called digital society?

Brandeis’ views did not enjoy universal acclaim. Others at the time, including President Theodore Roosevelt, felt there were areas with legitimate economies of scale, and that large enterprises could achieve higher efficiencies and lower prices to consumers in the production of goods and services by virtue of the volume of production. The evolution of auto manufacturing (in the early twentieth century) and the electricity industries both took exotic and highly expensive products and applied massive scale to the production process. The results were products that were affordable by many, if not all, and the impact on society was truly transformational.

The US administration of the day acted to implement regulatory oversight over these corporate behemoths, but not necessarily to dismantle their monopoly position.

Regulation?

But if the only oversight mechanism is regulation, have we allowed the major corporate actors in the digital service sector to become too big to regulate? Any major enterprise that can set its own rules and then behave in a seemingly reckless fashion is potentially damaging to the larger economy and the stability of democracy. One need only mention “Facebook” and “elections” in the same sentence to spark some strong opinions about this risk of apparently reckless behaviour.

To quote Brandeis again: “We believe that no methods of regulation ever have been or can be devised to remove the menace inherent in private monopoly and overwhelming commercial power.”

But if we reject Brandeis’ view and believe that regulation can provide the necessary protection of public interest, then it is reasonable to advance the proposition that we need to understand the activity we are attempting to regulate. Such an understanding might be elusive.

In the digital networking world, we are seeing more and more data traffic go ‘dark’. Content service operators are using their own transmission systems or slicing out entire wavelengths from the physical cable plant. This withdrawal of traffic from the shared public communications platform is now not only commonplace, but the limited visibility we have into this activity suggests that, even today, the private network traffic vastly overwhelms the volume of traffic on the public Internet, and the growth trends in the private data realm also is far greater than growth rates in the public Internet.

How can we understand what might constitute various forms of market abuse, such as dumping, deliberate efforts to distort a market, or discriminatory service provision when we have no real visibility into these private networks?

Yet these private networks are important. They are driving infrastructure investment, innovation, and indirectly driving the residual public network service. Are we willing and able to make an adequate case to expose (through various mandatory public filings, reports, and measurements), the forms of use of these privately owned and operated facilities and services? Do we even have the regulatory power to do so considering the size of the entities we are dealing with?

We have seen in the past that many national regimes have attempted to avoid the test of relative power by handing the problem to another jurisdiction. The anti-trust action against Microsoft was undertaken in Europe and it could be argued that the result was largely unsatisfactory. Even if we might believe that greater public exposure of the traffic carried by the dark networks might be in the public interest, we may simply not have the capability to compel these networks operators to undertake such public reporting, in any case.

Consolidation?

The Internet has been constructed using several discrete activity areas, and in each area, appeared to operate within a framework of competitive discipline. Not only could no single actor claim to have a dominant or overwhelming presence across the entire online environment, but even in each activity sector there was no clear monopoly position by any single actor.

Carriage providers did not provide platforms, and platform providers did not provide applications or content. The process of connecting a user to a service involves a number of discrete activities and different providers. The domain name being used came from a name registrar, the DNS lookup was an interaction between DNS resolver application and a DNS server host, the IP address of the service was provided by an address registry, the credentials used for the secured connection came from a domain name certification authority, the connection path was provided by several carriage providers, and the content was hosted on a content delivery network, used by the content provider. All of this was constructed using standard technologies, mostly — but not exclusively — defined by the IETF.

This diversity of the elements of a service is by no means unique, and the telephone service also showed a similar level of diversity. The essential difference was that in telephony the orchestration of all these elements was performed by the telephone service operator. Within the Internet it appears there is no overarching orchestration of the delivered composite service.

It would be tempting to claim the user is now in control, but this is perhaps overreaching. Orchestration happens through the operations of markets, and it would appear that the market is undertaking the role of resource allocation. However, the user does have a distinguished role, in that it is the users’ collective preference for services that drives the entire supply side of this activity.

But this is changing, and not necessarily in a good way. Services offered without cost (I hesitate to use the term ‘free’ as this is a classic two-sided market where the user is in fact the ‘goods’ being traded between advertisers and platforms) to the user have a major effect on user preferences. However, there is also the issue of consolidation of infrastructure services.

As an example, Alphabet not only operates an online advertising platform, but also a search engine, a mail platform, a document store, a cloud service, a public DNS resolver service, a mobile device platform, a browser, and mapping services, to name just a few. In this case it appears to be one enterprise with engagement in many discrete activities. The issue with consolidation is whether these activities remain discrete activities or whether they are being consolidated into a single service.

With various corporate mergers and acquisitions, we are witnessing a deeper and perhaps more insidious form of consolidation within the Internet than we’ve seen to date. Here, it’s not the individual actors that are consolidating and exercising larger market power but the components within the environment that are also consolidating. Much of this is well outside of the realms of conventional regulatory oversight, and is the result of vertical integration, where what we thought of as discrete market sectors are being consolidated and centralised.

The Economics of Advertiser Funding

The question remains as to how a small set of dominating incumbents retain their overarching position?

I suspect that advertising is playing a fundamental role in today’s Internet, in the same manner as it has played in the past in other consumer-oriented mass market communications systems, including traditional press, television, and radio.

Conventionally, the ‘total value’ of a market is based on the sum of the value of the goods or services traded within that market. In this framework the implication is that any investment in market disruption through the development of innovative responses to meeting the demands expressed within the market is implicitly limited by the net current value of the market. The innovation by any actor is intended to allow the actor to gain greater market share, while the overall value of the market is limited by the current value of the larger economy in which the market operates.

However, the use of advertising as a source of revenue has transformed many markets in the past, such as the press, radio, and television. Advertising allows the value of future consumer decisions to be brought to bear on the current market, potentially increasing the value of the current market by a proportion of the expected future value of the market. Market actors who use advertising as a source of revenue are no longer seeing the total value of the market just in terms of the total value of current transactions, but instead are able to factor in some proportion of future transactions. This higher valuation of the market on the part of the advertising platform can then justify increased investment in the market development and innovation based on this higher valuation.

It appears that advertising-based vehicles have, to a very large extent, an advantage in the market. But why is this market prone to consolidation? Why is this a winner-takes-all form of market dynamics?

It appears that there are very real dynamics of scale in advertising. Advertisers want their message to be seen by the greatest number of potential consumers, and advertising platforms want to provide a service to the greatest number of potential advertisers. The larger the platform, the greater the potential of the platform to meet both requirements. The result is an intense pressure to consolidate in this market, and that is what we are seeing. Of course, the Internet is now inexorably entwined in this situation.

We wanted the Internet to be ‘free’ and today it certainly is. I can use a search engine to query a massive compendium of our accumulated knowledge and more, without paying a cent! I can access tools and services for free. I can store all my digital data without cost to me. It sure looks like a free Internet to me! But is the inevitable cost overarching centrality and dominance by a small collection of global megalithic enterprises that distorts much of the rest of the global economy?

Re-Regulation?

In an earlier time, the Internet was seen as a poster child of deregulation of telecommunications regimes.

Entrepreneurial private sector investment was revolutionising a bloated and sluggish telco sector, applying the efficiencies of digitisation of information and services into a broad range of service sectors. This has transformed retail banking, the postal sector, entertainment, transport, government, and many other areas.

But the intense level of disruption in these markets was unsustainable in the longer term, and what we’ve seen since then has been progressive consolidation. As economies of scale come into play, the larger market actors assume dominant positions and then create conditions of entrenched monopoly. A small number of digital platforms have amassed a greater level of value and a far greater level of market control than their telco predecessors could ever have contemplated.

Once more we are left contemplating how to deal with the result. There is no appetite to persist with market-based control mechanisms that were intended to replace the previous regulatory frameworks, but we are also facing a situation where ‘too big to regulate’ is very much a current risk.

We appear to be seeing a resurgence of expressions of national strategic interest. The borderless open Internet is now no longer a feature but a threat vector to such expressions of national interest. We are seeing a rise in the redefining of the Internet as a set of threats, in terms of insecurity and cyber attacks, work force dislocation, expatriation of wealth to these stateless cyber giants, and many similar expressions of unease and impotence from national communities.

It seems to be a disillusioning moment where we’ve had a brief glimpse of what will happen when we bind our world together in a frictionless, highly capable, and universally accessible common digital infrastructure — and we are not exactly sure if we really liked what we saw.

The result appears to be that this Internet we’ve built looks like a mixed blessing that can be both incredibly personally empowering and menacingly threatening at the same time!

This article was originally published on the APNIC Blog on 7 June.

Comments 0

The comments section is closed for articles published more than a year ago. If you'd like to inform us of any issues, please contact us.