Electronic government (e-gov) lets citizens interact with their government via the Internet. The DNS, which maps e-gov domain names to Internet addresses, underpins e-gov. Working with the University of Twente and NCSC-NL, SIDN Labs compare the resiliency and redundancy of e-gov domains for the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, and the US.

E-gov adoption has grown steadily and has been recently accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. E-gov saves costs, provides faster services, and makes access for people with disabilities and mobility challenges easier. The figure below shows a subset of e-gov services provided by the Delft municipality in the Netherlands: you can make appointments, register your address, scheduling marriage or partnership services, and more.

E-gov services are provided over the internet, and the DNS is one the internet's core services. Therefore, if the DNS fails, domains can become unreachable, jeopardising the ability of governments to deliver services to their citizens. Just recently, several state government websites in the United States were victims of a DDoS attack, becoming unreachable.

Given such risks, it is of paramount importance that the DNS services of e-gov domains are properly configured with maximum levels of redundancy to withstand disruption or stress. Getting that configuration right is not always easy; DNS has many moving parts, and some are complex and or difficult to configure.

So we set out to assess the DNS configurations of e-gov domains to see whether they provide enough redundancy at different layers.

Datasets

It turns out it is hard to obtain a list of e-gov domains per country: many countries use their own ccTLD for e-gov domains, but there is no public list of e-gov domains that governments provide.

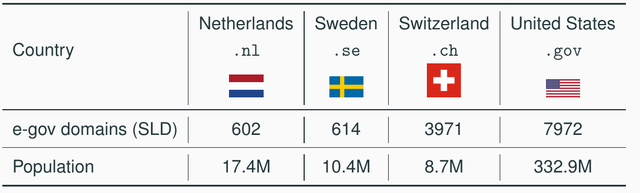

What we did instead is to use four different countries from which we could obtain data: our contacts in the Netherlands, Sweden and Switzerland provided us with the curated list, while the US .gov domain names are publicly available. The table below shows the number of domain names (second level domain, such as example.nl) we have obtained per country, and their population.

Results: DNS providers

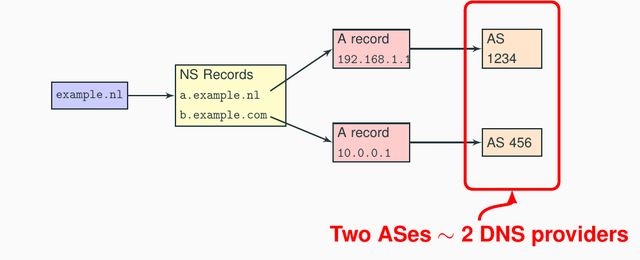

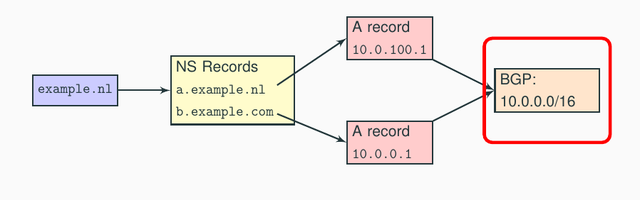

In the first metric we look into, we count how many distinct DNS providers e-gov domain names have. For example, in the figure below, example.nl has two NS records, each one of their own IP addresses, which are announced by two different Autonomous Systems (ASes), so we say it has two DNS providers.

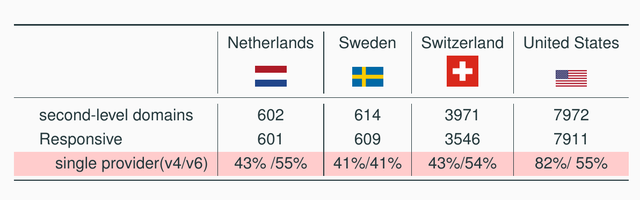

We see that roughly 40% of the NL, SE, and CH e-gov domain names have a single DNS provider (over IPv4). For the US, we see 82% of e-gov domains have a single provider.

One could argue that this is a bogus metric – if you host everything on a cloud provider, it ought to be OK. Well, clouds also occasionally fail, as AWS and Dyn have shown. And not even Amazon.com uses AWS for DNS - they rely on two external DNS providers. While we do not speak for them, we suspect that is for the same reasons - i.e. redundancy.

DNS market is highly local

So who are those DNS providers? The table below shows the results. It turns out that DNS services are heavily localised – local companies dominate the market. We believe this is because of the freedom of choice that local governments have in choosing DNS and hosting services; they may choose their traditional local companies.

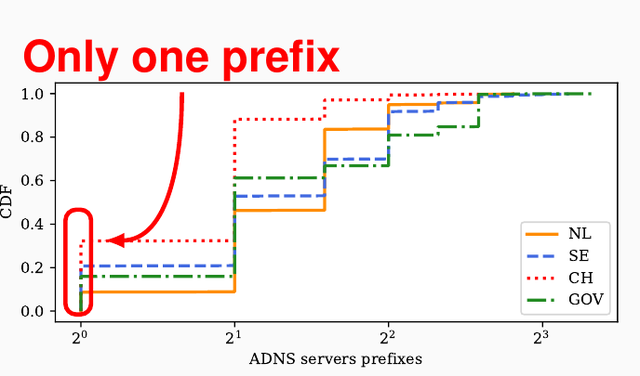

Results: number of routing prefixes

If the DNS servers of an e-gov domain name share the same routing prefixes, it means they are announced from the location(s), and hence, are not topologically diverse. It creates a false sense of redundancy, given they share large parts of networking infrastructure. An attack against servers in these prefixes could compromise the reachability of the e-gov domain names.

We then the number of prefixes, as shown in the figure below: the number of BGP prefixes we find in routing tables that match the IP addresses of the e-gov DNS servers. We use CAIDA's IP to prefix datasets.

We see that roughly ⅓ of the Swiss e-gov domain names are announced by a single prefix, where the others are under 20%. This creates unnecessary risk, and we recommend operators from these domains to diversify their networks to increase their resilience and minimise the chances of collateral damage.

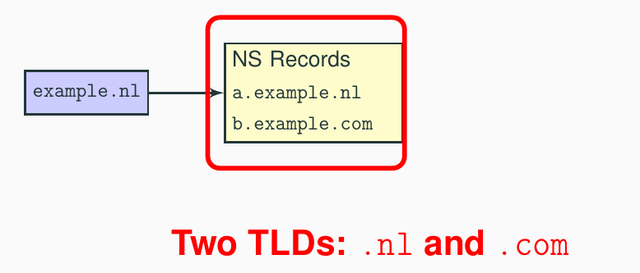

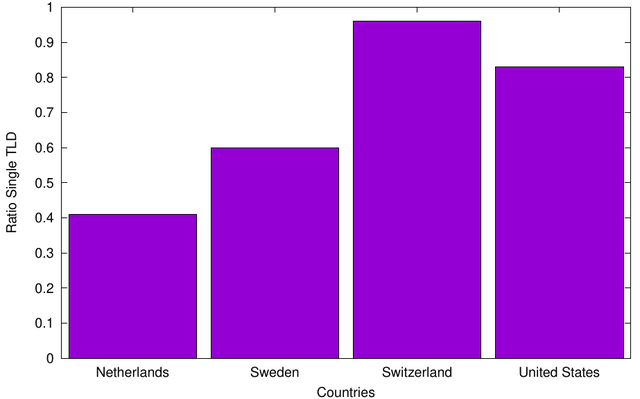

Results: number of TLDs

The next metric we measure is the number of top-level domains (such as .nl and .com) that each e-gov domain has for its DNS servers. For example, in the figure below, we see that there are two TLDs (.nl and .com) for this domain. If even one of these TLDs were to become unreachable for some reason, resolvers would still be able to reach the other TLD authoritative servers and ultimately retrieve the DNS records of their e-gov domain.

The results are as follows: in last place, we have Switzerland, with more than 90% of the Swiss e-gov domains having a single TLD in their authoritative servers – in this case, it's the .ch TLD, which is Switzerland's ccTLD. In third place, we have the US, with 83% of its domains depending on a single TLD (.com). Sweden ranks second with 60% of its e-gov domains depending on a single TLD(.se), and the Netherlands e-gov fares better, with still high 40% of the e-gov DNS servers depending on single TLD (.nl).

Why so much dependency?

We believe that the reason for these results is that many of these websites are from local governments, and they may typically use whatever DNS services their registrar provides. As such, they are at mercy of the policy decisions taken by their registrars: if a registrar has a diverse set of TLDs, they automatically benefit from it. An option would be to adopt a second DNS provider that employs different TLDs.

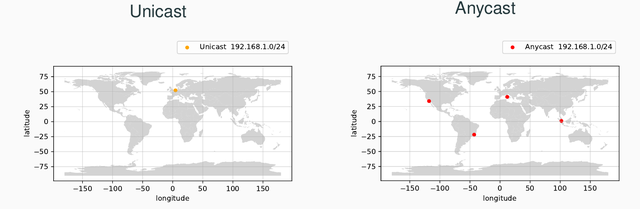

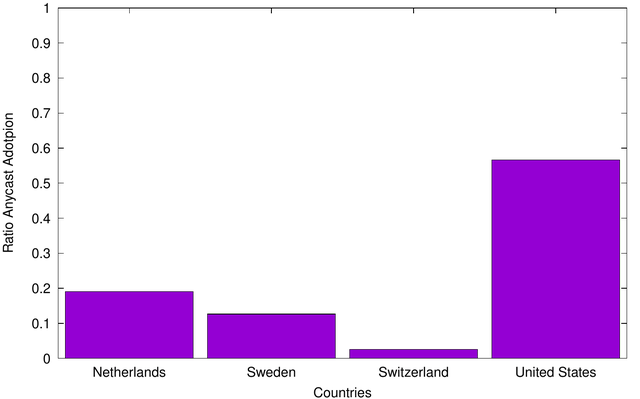

Results: anycast adoption

IP anycast is a technique that allows the same IP prefix to be announced from multiple locations. Traditionally, IP prefixes were announced from a single physical location. With anycast, you can announce the same prefix from multiple locations worldwide, as the figure below.

In this way, traffic is distributed among the anycast locations and it becomes harder to DDoS an anycast network – some sites may remain up whereas others may remain active, delivering service. We have investigated how anycast reacts to DDoS and presented considerations for anycast operators to use anycast in an informational RFC.

So let's see how is anycast adoption by e-gov domains: we see that it's actually quite low for the European countries – Switzerland has fewer than 3% of its e-gov domains having at least one anycast server. The better performing is the United States, with over 55% of its e-gov domains on anycast services. Netherlands has around 20%, while Sweden has 12%.

Similarly to TLD usage, this has to do with the operation decisions taken by registrars and DNS providers chosen by the e-gov domain name operators. They could improve it by deploying secondary anycast providers.

Wrapping up

E-gov domains play a crucial role in many countries. We have measured four countries, and have shown that their e-gov DNS services can still be improved and be made more resilient by adding extra redundancy in terms of DNS providers, routing prefixes, TLDs and adopting IP anycast.

We refer the interested reader for our peer-reviewed paper with all the experiment details and extra results, and to our RIPE86 meeting presentation.

Comments 0

The comments section is closed for articles published more than a year ago. If you'd like to inform us of any issues, please contact us.