The Internet is a network of networks administered, controlled and shaped by humans. As such, it is as much affected by power relationships across the public and private actors as it, in turn, affects them. In this article, the team from GEODE explores the complex relations between the technical and political dimensions of the Internet, this time with a focus on Central Asia.

This RIPE Labs article is the first of a 2-part series that present the result of a Research project called “Mapping Connectivity in Central Asia: A View from Within” carried out by researchers from the GEODE center (Paris 8 University) and supported by RIPE RACI Project Funding.

Understanding the relationship between the structure of networks and geopolitics raises challenges related to the availability of data - including incompleteness of routing information and the lack of insight into the political considerations underpinning the actions of network operators.

The purpose of this article is to expound on how using qualitative data gathered “in the field” can enhance our understanding of the complex relations between the technical and political aspects of the network.

Taking Central Asia and Kyrgyzstan as our focus, we show how interacting with local actors helps in gaining a deeper understanding of how geopolitical events such as the war in Ukraine can affect the architecture of networks, and highlights causes for the lack of interaction between local network operators and international organisations.

Introduction

Since the onset of the war in Ukraine, major stakeholders of the Internet infrastructure - including Russia, Ukraine, private transit providers, and IXPs - have demonstrated their capacity and intention to alter or manipulate the public Internet for geopolitical reasons. This ability has illustrated, with a renewed intensity, a fundamental principle of the Internet – that it is a sociotechnical network, administered, controlled and shaped by humans that depend and act on power relationships. Conversely, the architecture of Internet infrastructures affects power relationships and equilibria around the world.

However, understanding this dialectical relationship raises various challenges related to the quality and reliability of available data. First, routing information is not complete, and the market evolution of the network makes it increasingly complex to understand its geographical characteristics. Second, we typically lack reliable information on the geopolitical motivations and views that drive or underpin the actions of network operators.

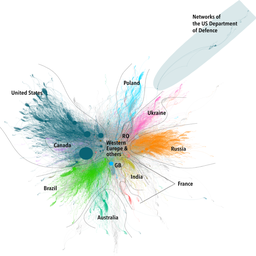

Combining routing data with other types of research, including Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT), we have been developing methodologies to understand and analyse the geographical properties of the control plane and its entanglements with geopolitical dynamics - i.e. how the network impact relationships of power on one hand, and how geopolitics affect connectivity on the other.

The purpose of this article is to expound on how gathering qualitative data through fieldwork can enhance our understanding of connectivity and its geopolitical underpinnings, as well as to identify the discrepancies between observations from routing data and information collected from local actors. We have chosen the region of Central Asia as a case study. The relative simplicity of the Central Asian network, the remoteness of the region, and the evolving roles of important strategic actors - i.e., China and Russia, Turkey, and Western Europe - have led us to choose it as a specific case study.

We start by providing a short analysis of connectivity in Central Asia, as observed from BGP feeds and through a visualisation methodology described in Geopolitics of Routing. We then describe the main findings drawn from our interviews with local actors.

The connectivity in Central Asia as seen by BGP feeds

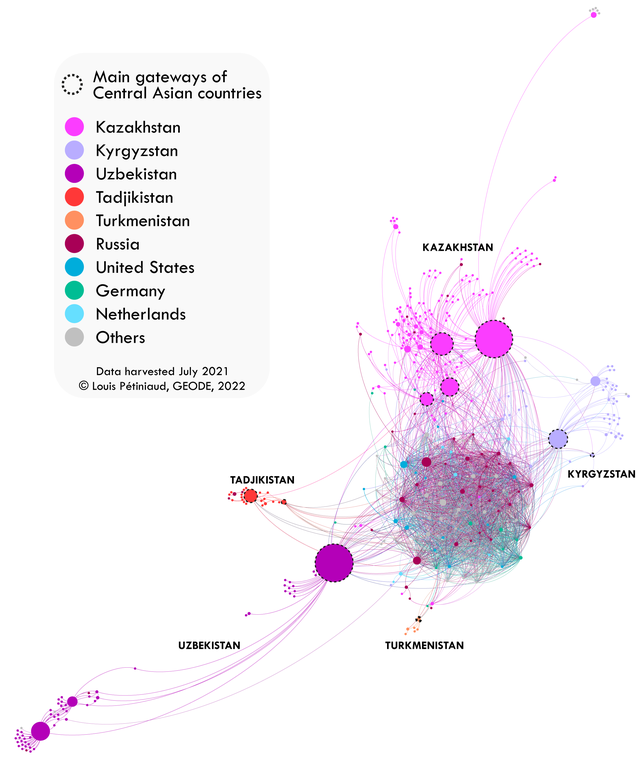

To gain insights into the general internal and external connectivity of the Central Asian region, we examined how the States of the region connect to each other and the rest of the world. The graph below represents the autonomous systems (ASes) of Central Asia and their neighbours. The following graph shows this data for July 2021.

Each node of the graph corresponds to an autonomous system, coloured according to its country of registration and whose size is proportional to its betweenness centrality (BC). The edges represent adjacencies between these systems, inferred by the GEODE BGP tool. Strictly speaking, betweenness centrality measures how frequently the shortest path between two other nodes passes through the given node. In other words, "in a communication network, the betweenness centrality of a node can be considered as the probability that information transmitted between two nodes passes through this intermediate node".

In the context of Central Asia, where networks are rather centralised, the BC value highlights, in most cases, the gateways between Central Asian countries and the rest of the Internet. Finally, these nodes are spatialised in a two-dimensional space by the force algorithm Force Atlas 2. This algorithm is based on a concept of repulsion: it simulates a mechanical system. The nodes naturally repel each other, but the interconnections attract them to each other, like springs. Thus, the closer two ASes are on the graph, the more neighbours they share.

This connectivity graph illustrates important insights into the structure of national networks in Central Asia and their relations with external actors. The graph reveals that the five national networks are relatively evenly distributed around a group of foreign AS, indicating weak interconnectivity between Central Asian countries. Moreover, it underscores the prominent role of external actors in intra-regional connectivity, as local actors are mainly connected through Russian AS, which comprises more than 11% of the graph's AS.

The Kazakh network is more diversely connected to the core group, which can be explained by infrastructural aspects: directly connected to Russia, Kazakhstan can take advantage of the presence of Russian infrastructure to connect directly to foreign actors transiting through Russia. Examining each country’s networks individually shows more precisely the important differences in the organisation and their geopolitical consequences. We analyse these networks starting from the simplest to the most complex.

The Internet network of Turkmenistan is both simple and relatively stable. The country connected since 2015 via two operators, the state-controlled Russian operator Rostelecom (AS 12389), the other to Rostelecom and to the Indian US-registered Tata Communications. A connection appeared more recently from TurkmenTelecom (AS 20661) to the Azerbaijani provider DeltaTelecom (AS 29049). This change is geopolitically significant, as it accurately echoes Azerbaijan's evolving strategic and commercial interests.

The Tajik network is concentrated around TojikTelecom and Avestonet, the country's two main gateways to the Internet. Tajikistan's network is indicative of the country's regional isolation, being connected only to Kazakhstan through SA TTC. It is worth noting the presence of a connection with China through AS 47139 and ChinaTelecom (AS 4809). One of the remarkable phenomena of the Tajik network is its trend towards centralisation. Since 2015, the dynamics of centralisation around 2 gateways serves a strong objective of network control, which Reporters Without Borders considers an adoption of the Chinese model.

Uzbekistan's network is the most centralised in the region: Uzbeks can only access the rest of the Internet through UzbekTelecom (AS 28910). This internal centralization of the network is an important phenomenon, which also supports a policy of censorship and control. However, UzbtekTelecom is increasing the number of its providers, and it is now connected to seventeen different states including the USA, China, and EU states.

The Kyrgyz network, is also quite highly centralised. The national operator Elcat is a key gateway. Founded in 1994, the company has since the 2010s focused on building physical infrastructure to connect the country to its neighbors: Kazakhstan in 2009, China and Tajikistan in 2012. Aknet appears to also stand as a major gateway for many Kyrgyz ASes, mostly for companies, especially Kyrgyz banks (including the country's national bank). Aknet was created as an academic network, dedicated to the country's universities, whose ambitions have grown. Kyrgyzstan nevertheless has several gateways to the outside world including MegaLine and TelcomData. Overall, Kyrgyzstan again shows the importance of Russian providers, which make up 30% of the country's neighboring ASes.

The network of Kazakhstan is much more extensive and complex than those of other Central Asian states and is structured around a greater number of intermediate-sized nodes. The network remains centralised, with four main gateways, TNS, KTC, TTC and KazTelecom. The position of KazTelecom is particularly remarkable as a provider: it is not only an essential gateway for the country, but also a central node in the regional architecture, serving as a provider for several large ASes in the region, both Kazakh and non-Kazakh.

The view from BGP feeds informs us on a variety of characteristics of both the architecture of connectivity, the market ecosystem, and the concentration of Internet access. Most of all, it considering the importance of Russia in Central Asia’s neighbours, it suggests the dependency of these countries to Russian providers, which was confirmed by our fieldwork as well by other metrics. The understanding of what shapes connectivity in the region remains, however limited. To address these limitations, and gain a more holistic understanding of network dynamics, we conducted a fieldwork in April-May 2022.

Setting up a fieldwork to understand connectivity

Our fieldwork in Kyrgyzstan was performed between 13 April, 2022 and 5 May, 2022. We visited various areas of the country, mostly along the North-South road between the capital Bishkek and the “Southern capital”, Osh. Due to limited time and resources and the security constraints, we would have encountered in the other Central Asian countries, Kyrgyzstan has served both as a case study and as an illustration of the region’s dynamics. We believe that Kyrgyzstan provides an accurate entry point in the region and highlights a range of dynamics that pertain to the architecture of networks.

We conducted interviews with local actors of the network, in order to grasp the causes of the network’s structure, and the motivations of local actors when they make decisions that shape this architecture. We thus sought to gather information on routing directly from local operators and relevant stakeholders, as well as to understand the representations of these local actors on national connectivity, resilience, potential problems, and geopolitical stakes pertaining to it. We also researched the lack of efficiency and success of IXPs in the country, as well as the relative lack of communication between local actors and international organisations such as RIPE in terms of coordination, or PeeringDB in terms of registration.

From the interviews conducted, we managed to point out several important dynamics in the connectivity of the country, some of which are applicable to the wider region

- First, we found that there are no common and shared view of connectivity dynamics in the country. Each actor has its own representation depending from his point of view. This highlights the need for improved communication and collaboration among stakeholders to ensure a more cohesive understanding of network dynamics.

- Second, major geopolitical events have the potential to trigger some changes in the connectivity, mostly in the medium and long terms in the case of the war in Ukraine. This underscores the importance of monitoring geopolitical developments in the region and their potential impact on network architecture.

- Third, there is a lack of exchanges and communication between local actors and international organisations such as RIPE or PeeringDB, mostly because of a lack of understanding of the benefits of connecting with them. Addressing this issue could help improve connectivity in the region and enhance collaboration between local and international actors.

The lack of a shared understanding of the region’s connectivity

The first main finding of our work was that operators and policymakers do not agree on several important information about the network that could be useful to be shared at the national or regional level. There is also a lack of relevant organisations and fora that could be used for that purpose. First, regarding Kyrgyzstan’s internal or external connectivity, we have heard contradicting opinions on how the actual architecture of connection is shaped and how it should be shaped. Two examples highlight this situation: the Southern IXPs, and the connections with China, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan.

There are potentially two IXPs in the south of the country: the Ferghana Valley IXP (FVIXP) and another one. None of them is registered on PeeringDB. The Ferghana Valley IXP was launched in April 2019 and was funded by the Kyrgyz Internet Society Chapter. Publicised since April 2017. It is located in Osh, the country's southern capital, and was supposed to help develop the Internet in the whole region. According to the ISOC website, it was also conceived through “working closely with local stakeholders and community members to set up first of its kind peering hub". Despite local cooperation, ISOC members of Kyrgyzstan told us that the IXP was not in use because of a lack of Interest from operators, which was confirmed by one small operator from Osh, directly contradicting the FVIXP’s website. RIPE had already noted in Central Asia a global “reluctant attitude towards IXPs”. Our interviews helped pinpoint two central reasons for this: The bureaucratic hurdles and the lack of competent personnel from small operators.

The second example of these diverging views regards the connections (or lack thereof) with direct or indirect neighbouring countries, whether inside or outside the region. The case of the links with Uzbekistan and Tajikistan is especially telling. During interviews, two Kyrgyz actors suggested that there existed “invisible” paths used for data transit between Kyrgyzstan and both of these countries. For Tajikistan, most other actors acknowledged that it was a possibility, although some denied it. One important operator in the country suggested that there might be some unannounced traffic, but they were unaware of it despite their sizable footprint in the national network. According to most interviews, these unannounced routes stem from the geopolitical conflict between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, specifically, from decisions made by TojikTelecom to disconnect from Kyrgyz operators. While this long-lasting conflict between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan probably impedes the communication between the two countries, the uncertainty remains - there is no shared view about these unannounced paths between local operators.

The fact that there are such diverging views serves as an illustration of the overall lack of coordination between actors in the region. At the regional scale, the lack of coordination becomes even more obvious. Despite some organisations like the Eurasian Economic Union being described by some actors as sometimes serving as regional platforms, there is no cooperation between associations of operators of different countries. In fact, there is no contact at all between the Kyrgyz association of operators and others in the region, not even with Kazakhstan, from which connectivity mostly depends. Conversely, this association has strong links with Russian operators, which illustrates the strengths of strategical dependencies inherited from the imperial past of the post-Soviet area. Yet this lack of cooperation in Kyrgyzstan and the region may be changing at a fast pace. The war in Ukraine and the realisation of the very preeminent place of Russia in terms of regional connectivity could lead in the long term to a paradigm shift, a perspective which all the interviewees agreed on.

The effect of geopolitical events on connectivity

The network of Kyrgyzstan is very much dependent on Kazakhstan and Russia for its global access to the Internet. The country does have international providers from Western Europe and the US, but they all cross the territory of Russia. Some actors in the country see this as a fact rather than a fundamental political issue, including the Kyrgyz authorities in Digital development, who consider it "more of an obvious fact than a problem". When asked about the potential obstacles raised by this situation to develop some form of “digital sovereignty”, employees from this Ministry disregarded the question. It should be noted that, from the point of view of the authorities, this issue of sovereignty is decorrelated from connectivity: in their opinion, both the resiliency and redundancy of the network fall under the sole responsibility of network operators. Even if they fear Russia may use connectivity as a pressure point, including for gaining support (material or political) for the war, Kyrgyz authorities do not wish to interfere in the market at this level. On the other hand, some local operators expressed deep concerns about this dependency, stating that Russia could definitely use Internet as a pressure tactic toward central Asian countries for getting their support to the military operations. Our interviews were conducted in April 2022, 3 months after the beginning of the invasion of Ukraine, in a context of great geopolitical uncertainties.

The extent to which this dependency is prevalent remains difficult to measure. According to the association of network operators of the country, a potential disconnection from Russia would only lead to a decrease in traffic of about 20-25 % for Internet users, thanks to the alternative roads that the country has with its neighbours. But, apart from Internet access for users, this dependency entails more structural obstacles for Kyrgyz actors. One major operator indeed mentioned that they could not peer with Hurricane Electrics because, according to them, “Hurricane Electrics’ routers should have been registered in Russia”. In a more general sense, even though they do intend to “better their connectivity with Frankfurt”, they claim that it is not possible due to Russian policies.

Despite the trust in the ability of alternative routes to withstand most of the traffic, the war in Ukraine appears as a game changer. In Central Asia, the Russian decision to go to war with Ukraine has faced various types of cautious but sometimes firm criticism of the Kremlin’s actions. Central Asian countries are heavily dependent on Russia and thus are reluctant to openly raise their voice against Moscow.

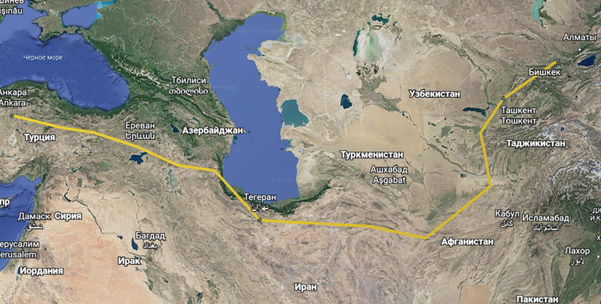

Regarding connectivity, this criticism materialised in our interviews through the interest shown by local actors in various potential solutions. Different plans to bypass or at least reduce dependency on Russia have indeed been mentioned, and sometimes praised during interviews. Two new infrastructures are mostly looked into by local actors - the TurkTelecom cable, and Starlink.

In April 2022, while we were on our fieldwork, Turkish and Kyrgyz providers Turktelecom and Elcat declared a Memorandum of Understanding on a future Ankara-Bishkek land cable connecting the two countries.

Still at an early stage, this possible future cable shows, according to one important actor, how the war in Ukraine has changed the view of Internet stability in the country, and how operators want to be able to bypass the Russia connection which could turn into an important problem.

Starlink is also an alternative being considered a potential provider to bypass the Russian stranglehold. Starlink sparked great interest but often with little knowledge of it, both in a broad technical way and news-related. However, according to the association of network operators, “the war in Ukraine is an incentive for [network operators] to look into satellite communications, and this question clearly stemmed from the news. The war has brought back the obvious realisation of the isolation of the country.”

Finally, it should be noted that China was rarely mentioned, and at least never considered a viable alternative to Russian dependency. The reason mentioned by all interviewees is that all resources needed by the population are never located in China, and that there is no economic incentive to develop the connectivity with their eastern neighbour. Yet Chinese plans for future infrastructural investments in Central Asia and Western China, under the scope of its gigantic infrastructural plans for the One Belt One Road initiative, are substantial. In the long term, these investments could increase the redundancy of the regional network, but they do not elicit a strong interest in local stakeholders.

Major geopolitical events such as the invasion of Ukraine can definitely trigger significant changes in the perspectives of connectivity for a given region. Russia appears in Kyrgyzstan today not as a mere provider anymore, but as a major actor with a strong infrastructural power inherited from its imperial past. The aggressive actions led by Moscow in Ukraine have directly led to a strong change in the country’s geopolitical representations. Even though digital sovereignty and network redundancy are entrusted by the State to private operators, this shift in Kyrgyz representations have triggered the potential for major reconfigurations in infrastructures and routing.

The lack of cooperation with international organisations

Finally, our work has helped understand some of the reasons why there is a relative lack of cooperation between local actors and some international organisations. We have focused our interviews around RIPE and PeeringDB.

Through our interviews, we have identified a primary reason for the lack of engagement with these entities: a perceived lack of interest. In other words, many local actors, including influential figures in the national connectivity landscape, do not see a compelling incentive to participate in these organisations, indicating a lack of information on the benefits of doing so.

The same reason was brought up about PeeringDB. The other reason mentioned by one important provider was that many small operators in Kyrgyzstan lack the necessary skills and/or the time to do so. This was confirmed by an interview with a small operator, “if you are above the radar [registered], it costs more money, and you need to have technicians to better manage the network”. These challenges are not simply financial, as there is also a shortage of competent workforce in certain areas. For instance, some operators we spoke to lacked formal education but were self-taught in network administration.

Most actors are nevertheless interested in interacting with RIPE. The association of network operators indicated a willingness to register if they perceived an interest from RIPE and if they had an opportunity to engage with the organisation beforehand. As put by one of the people interviewed, “RIPE has never come to see us, nor to see how things are happening around here”. The high-ranking employee of a major Kyrgyz operator also had some grievances. He had ordered two RIPE Atlas probes a few years ago but he told us that, upon realising they could not get the probes to work, they say they tried contacting RIPE, to no avail.

Conclusion

The methodology described in this article and the outcomes of this research project demonstrate the usefulness of gathering qualitative data on the field related to the architecture of connectivity. This fieldwork helped us show how actors often hold divergent views on how the network should be structured and do not always cooperate with one another. Second, actors shape the network by considering different parameters, including geopolitical considerations. However inescapable their structural dependency appears to them; geopolitical events tend to trigger changes in the representations of actors and their priorities.

Understanding the geopolitics and geography of connectivity is a complex task, partly due to the incompleteness of available data from BGP feeds or active measurements and the lack of knowledge on geopolitical representations and motivations of actors. This study is an important example of the collaboration between computer and social sciences, which is necessary for a more holistic comprehension of the socio-technical network that is the Internet, including its geopolitical features and impacts.

Comments 0

The comments section is closed for articles published more than a year ago. If you'd like to inform us of any issues, please contact us.