DNS infrastructure is infamous for facilitating reflective amplification attacks. Countermeasures such as server shielding, access control, rate limiting and protocol restrictions have improved the situation, but DNS-based reflective amplification attacks persist. Focusing on the threat vector introduced by transparent DNS forwarders, our research shows they can provide access to shielded recursive resolvers and scale better in terms of potential attack volume.

Jump to our research paper: Forward to Hell? On the Potentials of Misusing Transparent DNS Forwarders in Reflective Amplification Attacks

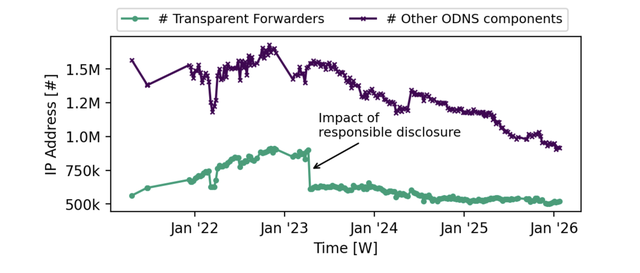

Over the past decade, the total number of open DNS devices has decreased from over 25M in 2014 down to 1.4M in 2026. These devices are often targets of attackers who misuse them as reflectors for DNS requests with spoofed source IP addresses. Over the past five years, we conducted weekly Internet-wide scans to monitor the open DNS infrastructure. Our analysis shows that the number of recursive DNS resolvers and forwarders (aggregated under ‘Other ODNS components’) constantly decreases while the number of transparent forwarders remains on the same level, although our responsible disclosure removed more than 250k devices from the threat landscape.

Transparent DNS forwarders

An often unnoticed threat derives specifically from so-called transparent DNS forwarders - a widely deployed, incompletely functional set of DNS components.

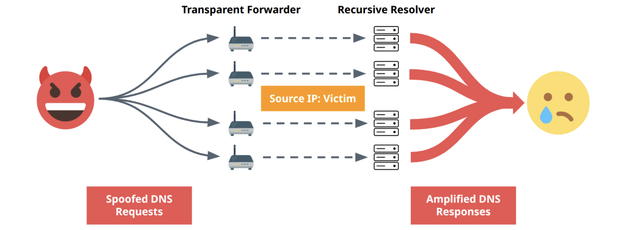

Transparent DNS forwarders transfer DNS requests without rebuilding packets. Therefore, for example, the source IP address included in the query forwarded to other DNS components (for example, recursive resolvers) remains the IP address of the original resolver.

Transparent forwarders raise severe threats to the Internet infrastructure:

- They feed DNS requests into (mainly powerful and anycasted) open recursive resolvers, which thereby can be misused to participate unwillingly in distributed reflective amplification attacks.

- They easily circumvent rate limiting and achieve an additional, scalable impact via the DNS anycast infrastructure.

- Transparent forwarders can also assist in bypassing firewall rules that protect recursive resolvers, making these shielded infrastructure entities part of the global DNS attack surface.

- In contrast to recursive forwarders, transparent forwarders do not need to handle the (potentially amplified) response, enhancing the effectiveness of an attack.

Distribution of transparent forwarder deployment

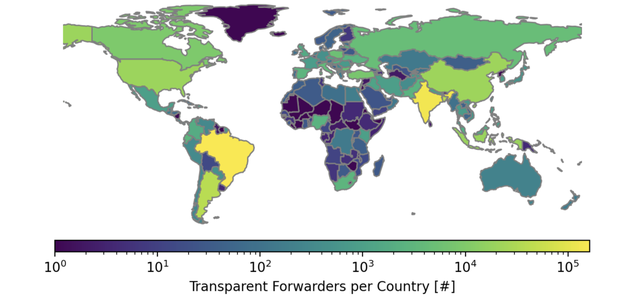

Transparent DNS forwarders are publicly accessible via the global Internet in 175 economies, with a strong bias towards Brazil (31%) and India (24%).

Our observations imply that attackers have access to a widely distributed infrastructure. 45% of transparent forwarders are located in 173 economies, with most of the remainder being in two economies. The concentration of the second group makes it possible to efficiently approach a smaller subset of operators to reduce the threat landscape.

Public DNS resolvers used by transparent forwarders

Transparent forwarders redirect the resource intensive recursive workload of DNS resolution to recursive resolvers that belong to a powerful infrastructure.

Our measurements show that a recursive resolver belonging to either Google or Cloudflare is configured on 76% of all transparent forwarders. An attacker that simply bases its attacks on recursive resolvers in general may prefer to target less powerful resolvers (for example, customer-premises equipment, or CPE).

| Public Resolver |

Transparent Forwarders Using Public Resolvers |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

IP Address |

Provider | [#] | [%] |

| 8.8.8.8 | 341,447 | 64.25 | |

| 1.1.1.1 | Cloudflare | 48,313 | 9.09 |

| 208.67.222.222 | OpenDNS | 14,464 | 2.72 |

| 8.8.4.4 | 14,115 | 2.66 | |

| 223.29.207.110 | Meghbela | 11,789 | 2.22 |

| 83.220.169.155 | Comss.one DNS | 2047 | 0.39 |

| 178.233.140.109 | Turksat | 1790 | 0.34 |

| 203.147.91.2 | Meghbela | 1634 | 0.31 |

| 1.0.0.1 | Cloudflare | 1196 | 0.23 |

| 103.88.88.88 | DNS Bersama | 1007 | 0.19 |

Broad range of affected vendors

We use a set of common fingerprinting techniques (like banner grabbing, and Simple Network Management Protocol, or SNMP scanning) and tools (ZGrab, SNMP scanner, and Selenium). We are able to fingerprint 13,072 (2.5%) of ~530k transparent forwarders. Even though this number is much lower than the overall number of transparent forwarders, global applicability still holds because we learn more details about this global subset, enough to derive performance properties of the potential attack infrastructure.

The majority of the identified devices are MikroTik routers (76%). Those MikroTik devices can be divided into core routers, which are powerful devices such as CCR2116-12G-4S+ or CCR1036-8G-2S+, and CPE devices such as RB750Gr3 or RB760iGS.

We observe routers as the major type of transparent forwarders, however, we also discover network video recorders such as HikVision or UNV IP-cameras.

While we are only able to map 2.5% of the transparent forwarder landscape to a vendor and device type, it is clear that transparent DNS forwarder behaviour is not limited to MikroTik. Although the fingerprinting is limited to a small sample, the identified devices are distributed in 1544 ASNs over 103 economies, therefore indicating a global trend.

Furthermore, transparent forwarders cover a broad range of devices, from constrained CPE up to powerful core routers. We summarise the results in the table below.

| Device Type | Vendor | Devices [#] |

|---|---|---|

| Router | MikroTik (Core) | 5569 |

| MikroTik (CPE) | 4362 | |

| TP-Link | 728 | |

| Ubiquiti | 663 | |

| Fortinet | 252 | |

| ZTE | 200 | |

| Cisco | 104 | |

| Zyxel | 102 | |

| Huawei | 58 | |

| D-Link | 24 | |

| Other | 114 | |

| Network Video Recorder | HikVision | 871 |

| UNV | 25 |

Transparent forwarders allow accessing shielded DNS infrastructure

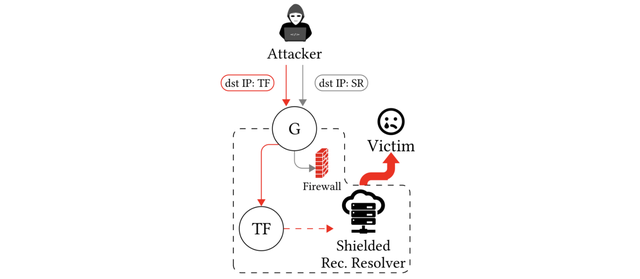

An attacker can take advantage of insufficient firewall rules to access shielded resolvers via using recursive resolvers that are protected by a firewall. While the network borders block traffic directly targeting these resolvers, the firewall of the DNS resolver does not validate the source IP address. Hence, an attacker can trigger responses from this (not so well) protected entity.

Transparent forwarders are not the only open DNS components that can bypass firewalls. Shielded resolvers can also be accessed indirectly through recursive forwarders. In contrast to recursive forwarders, however, transparent forwarders are less likely to be affected by rate limiting of DNS queries, because transparent forwarders aim to minimise states and assume any query to be legitimate.

Transparent forwarders exceed the constraints of recursive forwarders in attacks

Both transparent forwarders and recursive forwarders allow to bypass firewalls that protect shielded resolvers. Transparent forwarders, however, pose the unique security risk that they do not need to handle the amplified reply, which increases scalability of the threat landscape.

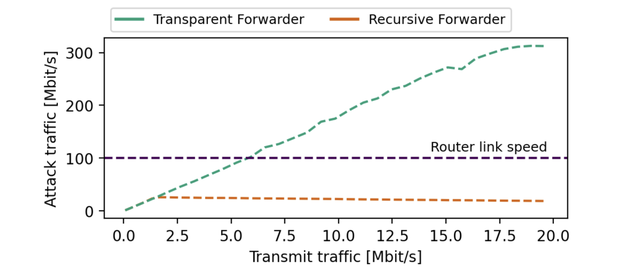

Comparing the limits of both types of DNS forwarders based on an Internet-wide measurement study would conflict with ethical concerns, and is therefore not in scope of this work. Instead, we gather empirical data in a lab experiment using the MikroTik router model RB750Gr3, which we also observe in the real world to reflect structural properties.

While we previously assumed that a recursive forwarder would be limited by its link speed, our testbed shows that the tested router already runs into resource limitations at 1.5Mbit/s of query traffic, resulting in ~50MBit/s attack traffic at the victim. In contrast, when configured as a transparent forwarder, we reach up to 320MBit/s at the victim without running into bandwidth limitations on the transparent forwarder side, highlighting the increased threat potential of transparent forwarders over recursive forwarders in DDoS amplification attacks.

In a nutshell

Transparent DNS forwarders significantly extend the attack surface of the open DNS infrastructure, and scale up reflective amplification attacks.

They scale better in terms of potential attack volume, and enable access to shielded recursive resolvers, exposing a further attack surface of the global DNS infrastructure. Networks with transparent forwarders do not implement network ingress filtering nor reverse path forwarding checks as transparent forwarders spoof the source IP address of their clients. The majority of transparent forwarders show consolidation in geographical diversity as well as configured recursive resolvers.

Mitigation options and advice for network operators

- Check your firewall rules and router configuration, as the network border can be bypassed for direct access to entities in your network. Always secure your infrastructure independently of the network firewall.

- Implement network ingress filtering or reverse path forwarding checks to prevent spoofing in your network.

- Configure rate limiting on your resolver infrastructure, it is often not necessary to allow thousands of requests per second coming from the same source IP address.

- Check if your networks or devices are affected: We publish our measurement results once a week – use our API to check your network!

More details are available in our publication Forward to Hell? On the Potentials of Misusing Transparent DNS Forwarders in Reflective Amplification Attacks presented at the Proceedings of the 2025 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security.

Comments 0