Route server exposure at IXPs leaves peering LANs vulnerable to routing leaks and real-world DDoS attacks. In this article, we talk about how and why it matters.

The Internet works thanks to a complex set of interconnected systems that operate behind the scenes. At the heart of this infrastructure are the Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) - crucial hubs where networks meet to exchange traffic directly and efficiently. To keep things running smoothly, IXPs operate route servers, which help automate how networks share routing information. However, these systems and the LANs they reside in are more exposed to the public Internet than many IXP operators think - with potential security consequences that are already actively abused.

At the heart of the issue is a common assumption: that route servers are mostly isolated and safe within the local IXP environment, because the peering LAN they reside in is not routed. While best practices such as those in RFC7454/BCP194 envisioned IXPs openly announcing their peering LAN prefixes themselves, the modern Internet has moved toward stricter controls. Most IXPs today use RPKI AS0 records to prevent their LAN prefixes from being globally routed via BGP, signalling that these prefixes are considered private infrastructure. However, this protection applies only to Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) announcements; it cannot stop Interior Gateway Protocol (IGP) routes. The latter create a blind spot for IXPs where peering LANs are reachable from the public Internet even though their BGP visibility is properly restricted.

While IGP leaks of peering LANs are not entirely new, we quantify this hardly measurable (and manageable) exposure of peering LANs in the Default Free Zone (DFZ) for twelve IXPs for the first time using an active probing approach. We show this exposure has reached a high level (up to 27% of all routed ASes) especially for larger peering LANs. This opens the door to DDoS attacks on route servers and IXP member routers. In addition, we investigate the active abuse of IGP routes for DDoS into a major peering LAN.

How does it happen?

But let's first break down how IGP leaks actually happen. If a connected member network is leaking the peering LAN prefix into its own internal IGP, this can happen in at least two ways on the connected border router:

- The IGP configuration includes interface ranges that are too permissive. For example, in OSPF on Cisco devices, a statement like

network 0.0.0.0 255.255.255.255 area 0will include all configured interfaces in OSPF, including the one connected to the IXP peering LAN. This results in the peering LAN prefix being advertised within the IGP. The same is true analog in OSPFv3/IPv6. - If an EBGP-learned route from the peering LAN is propagated internally without rewriting the next-hop (next-hop unchanged), the next-hop remains an IPv4/IPv6 address from the peering LAN. To ensure reachability to that next-hop, the IGP must carry a route to the peering LAN prefix, which can lead to its injection into the IGP. To avoid this, the next-hop self option has to be used.

In theory, IGP leaks are contained to the leaking member. However, in practice IGP leaks of peering LANs in larger networks regularly make routes available to a lot of downstream networks, as many downstream networks use default routes pointing to their upstream. That means any packet addressed to a peering LAN injected into a downstream network will end up in the leaking upstream network and is routed to the peering LAN. This effect is a very large multiplier regarding peering LAN exposure.

Measuring DFZ exposure of peering LANs

To quantify the visibility of twelve (not only DE-CIX) peering LANs from the routed ASes, we use an active probing approach. We send ICMP packets with a spoofed source address from the peering LAN via a transit link to all routed IPv4 addresses; i.e., we walk the whole IPv4 space with spoofed ICMP and measure who replies back into the peering LAN. Any ICMP replies received in the peering LAN are obviously sent from ASes with a route. Afterwards, we count the number of ASes that replied back and list them in the following table:

| IXP ID | Member ASes | DFZ ASes having a route | % of DFZ routed ASes | Leaking factor=DFZ routed ASes/member ASes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IX 0 | 999 | 20,602 | 27 | 20.6 |

| IX 1 | 830 | 16,847 | 22.1 | 20.3 |

| IX 2 | 808 | 15,554 | 20.4 | 19.3 |

| IX 3 | 261 | 7,136 | 9.3 | 27.3 |

| IX 4 | 213 | 2,295 | 3 | 10.8 |

| IX 5 | 185 | 2,879 | 3.8 | 15.6 |

| IX 6 | 179 | 2,318 | 3 | 12.9 |

| IX 7 | 171 | 2,412 | 3.2 | 14.1 |

| IX 8 | 109 | 3,810 | 5 | 35 |

| IX 9 | 60 | 2,702 | 3.5 | 45 |

| IX 10 | 56 | 1,974 | 2.6 | 35.3 |

| IX 11 | 20 | 2,126 | 2.8 | 106.3 |

| Median | 20.5 |

Even the smallest peering LAN of IX 11 (20 members, last row) is reachable from more than 2,000 ASes. This IXP seems to be extraordinarily unlucky, as a few leaking members are very large network providers. At the upper end of the table, there are three IXPs with more than 800 connected members. These IXPs are reachable from between 20-27% of all routed ASes.

Active abuse: from theory to 100 Gbps of practice

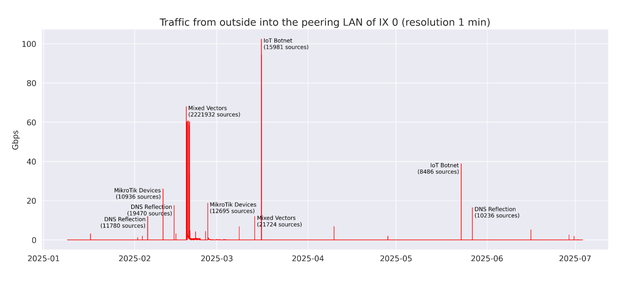

At this point you might ask yourself: "Some peering LANs are widely routed. Who cares?" Unfortunately, DDoS on infrastructure hosted in a peering LAN is not a theoretical scenario. In fact, this investigation into IGP leaks was triggered by a DDoS incident in a major peering LAN in November 2024. Since then we have monitored the issue and found at least nine similar incidents with bandwidths between 10 to 100 Gbps (see below).

While some of the observed traffic spikes could be clearly linked to well-known vectors such as DNS reflection, others were less straightforward due to ambiguous transport port usage. This prompted us to dig deeper into the data and actively investigate the source IPs.

In several cases, we identified MikroTik routers as being involved. Other infrastructure providers have also reported large-scale abuse of MikroTik devices, likely due to attackers exploiting the vendor’s bandwidth testing feature. In another case, we traced traffic back to publicly accessible IoT cameras. By analysing the video feeds, we were able to confidently determine both the origin (based on the feed) and the type of device.

In summary, our investigation demonstrates that routing-based DDoS attacks targeting IXPs are not just theoretical - they are feasible and already happening. Even simple reflection attacks via leaked IGP routes into peering LANs are effective. More sophisticated methods, such as the abuse of IoT botnets, are equally viable. The techniques are well within reach of attackers today. While we don’t claim to know the intent behind every incident, the technical groundwork for targeted abuse is clearly in place. Unlike most web infrastructures, IXPs generally cannot rely on DDoS mitigation services, and many may not even realise that their peering LANs are publicly reachable.

The (unfortunate) role of RFC7454/BCP194

A contributing factor to today's exposure of IXP route servers lies in the operational guidance outlined in RFC7454/BCP194, a document offering best practices for securing BGP sessions and filtering prefixes. While it correctly emphasises prefix filtering, session protection, and IRR-based filtering, its guidance on IXP LANs is problematic. Specifically, Appendix A suggests that IXPs should originate their peering LAN prefix and advertise it via BGP, with members propagating the prefix to downstream networks. This design aimed to support PMTUD and loose uRPF, but it normalises the global routability of IXP infrastructure. In contrast, today’s IXPs widely deploy RPKI AS0 ROAs to explicitly signal that their peering LANs must not be routed. This shift renders RFC 7454's IXP guidance not only obsolete, but counterproductive. Despite its broader value in BGP OPSEC, the document inadvertently encourages practices that expose critical infrastructure to the global Internet. An update of RFC7454/BCP194 without the IXP related parts is currently under discussion at the IETF.

Conclusion

As our measurements show, IGP leaks have silently expanded the reachability of peering LANs to tens of thousands of ASes - creating an enormous DDoS surface especially for mid to large IXPs. This exposure turns even modestly priced DDoS-for-hire services into a threat against critical Internet infrastructure. IXPs and their members should treat peering LAN reachability as a matter of exposure management. That means tightening IGP configurations, rethinking OPSEC recommendations like those in RFC7454, and ensuring that traffic from the public Internet to the peering LAN is properly filtered.

Note

We would like to thank Stavros Konstantaras (AMS-IX), Mo Shivji (LINX), Marta Burocchi and Flavio Luciani (NAMEX), and Wolfgang Tremmel (DE-CIX) for supporting the measurements and/or for giving feedback. Last but not least, Dorian Arnouts (DE-CIX) supported this work by coordinating and executing the measurements across different IXPs and analysing the data. The content was disclosed to EURO-IX 100 days prior to publication.

Comments 0