In the second of our IRR landscape series, we focus squarely on data quality: how accurate, current, and usable IRR routing data really is. Using freshness, DFZ alignment and RPKI conflicts, we spotlight where third-party IRRs drift and why cleanup matters.

This article is part of a series inspired by discussions on the connect-wg mailing list on a BCOP proposal on fading out non-RIR Internet Route Registries (IRRs) at IXP route servers. The series provides an overview on the IRR landscape, in particular how ASes use IRR databases, how good the data quality in different IRR databases is, and an impact analysis of the BCOP at two major IXPs.

In the previous part of this series, we examined how Autonomous Systems (ASes) use Internet Route Registry (IRR) databases to store their routing policy information, focusing on where this data is stored and how much of it exists. In this article, we shift our attention to the quality of the stored data.

But what does "data quality" mean in the absence of a definitive ground truth, especially in the context of IRR DBs? Since we cannot know the exact intentions of network operators when creating IRR objects (after all, they may have good operational reasons for doing things in a particular way), we must rely on proxy metrics that can give us an indication of data quality. In this article, we define several such metrics and evaluate them across all IRR databases listed on irr.net.1

As discussed previously, IRR databases are not all the same. We distinguish between two main groups:

- Authoritative databases, operated by Regional Internet Registries (RIRs) or their official delegates (AFRINIC, APNIC, ARIN, IDNIC, JPIRR, LACNIC, NIC.BR2, NIC.MX and RIPE);

- Third-party databases, which include RADB, NTTCOM, LEVEL3, RIPE-NONAUTH3, TC, ALTDB, BELL, REACH, CANARIE, BBOI, PANIX, and NESTEGG operated by private companies or NGOs.

This distinction matters because RIR-operated databases have access to authoritative information on IP address ownership; i.e., the data they directly manage and allocate. As a result, these databases typically enforce stricter access controls and validation procedures, ensuring higher reliability in the data they contain.

If you’d like a refresher on what IRRs are, how they work, and how they document the routing policies of ASes, we recommend revisiting the Background section of the previous article.

Defining data quality

As noted above, we rely on proxy metrics to assess data quality of RPSL objects stored in the databases across Internet Routing Registries (IRRs). Our analysis focuses on IPv4 and (primarily) on ROUTE objects. While IPv6 is an important consideration, it falls outside the scope of this work. The metrics used for this assessment are as follows:

- Update frequency. Frequent, recent edits suggest an operator is actively maintaining intent as networks evolve (new peers, prefix changes, mergers). Long-dormant objects are more likely to be stale, reflecting past topology or contacts.

- Alignment with the Default-Free Zone (DFZ). When RPSL objects (e.g., ROUTE, AS-SETs) correspond to what is actually propagated in the DFZ (correct origin AS, plausible prefix lengths), it indicates that the data describes operational reality rather than paper policy. Persistent gaps (objects that never surface in BGP) or occasional mismatches can be benign (pre-provisioning, backup paths, or traffic-engineering specifics), so some deviation is expected and the metric is not suitable to make claims in absolute terms. However, it is useful to do relative data quality comparisons between IRR databases.

- Conflict with higher-value sources (e.g., RPKI or authoritative information). Because RPKI ROAs provide cryptographic attestation of prefix-to-origin authorisation, contradictions - such as a ROUTE object authorising a different origin than a valid ROA - are strong indicators of inaccurate or unmaintained data.4 Similarly, discrepancies with authoritative information from RIRs, which hold the ground-truth allocation data, can signal that an RPSL object no longer reflects legitimate resource ownership. Conversely, consistency with both RPKI validation results and authoritative registry data increases confidence and hence its data quality.

Update frequency

We begin our analysis by examining the update frequency across all IRR databases. Unfortunately, AS-SET and ROUTE objects contain multiple timestamp fields - ”last-modified”, “changed”, and “created” - whose semantics differ across IRR operators. As a result, databases interpret and populate these fields inconsistently. To address this, we contacted IRR maintainers and incorporated their feedback on how timestamps are used within their respective systems (see Appendix A for details).

Previously, we have boldly claimed that update frequency is an indicator of stale data, a claim that we prove in the following plots. Therefore, we infer the point in time when a ROUTE object or AS-SET was last modified by an operator, using either its creation date or its most recent modification date, depending on the conventions of the specific IRR.

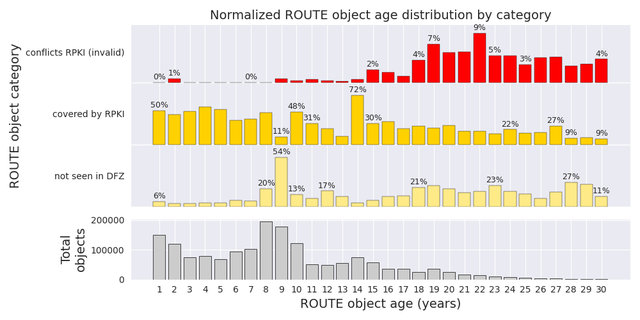

We first examine the distribution of ROUTE objects across three categories - "conflicts RPKI" (contradicts a ROA), "covered by RPKI" (covered by a ROA), and "not seen in DFZ" (not publicly routed) - as a function of object age, defined as the time since the last modification. The plot shows that older ROUTE objects (> 10 years) tend to be less relevant and less reliable.

Specifically, the fraction of objects classified as "not seen in DFZ" increases from an average of ~4% for objects aged 1 - 5 years, to ~18% for those between 26 - 30 years. Similarly, RPKI coverage decreases substantially with age, dropping from ~50% to ~15%. At the same time, objects are more likely to be in conflict with their covering ROA, increasing from an average of ~0.2% to ~4%. To put the last number into context, the current share of invalid routes in the DFZ is ~2% as reported by NIST.5

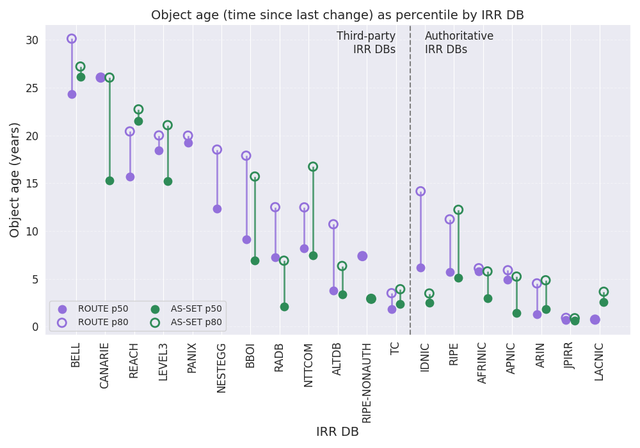

Following this observation, we present, for each database, the 50th and 80th age percentiles, representing the object ages below which 50% and 80% of entries fall, respectively.

The plot reveals a clear divide in data freshness between third-party and authoritative IRR DBs. Third-party IRR DBs show the broadest spread, with some databases such as BELL, CANARIE, REACH, LEVEL3, and PANIX exhibiting very old object ages: p80 values above 20 years and medians often exceeding a decade. Others, including BBOI, RADB, and NTTCOM, still contain many objects older than 10 years but show somewhat lower median ages. TC is a notable outlier within the third-party category, with object ages comparable to those in authoritative IRR DBs and far fresher than the other third-party IRR DBs.

Authoritative IRR DBs, on the other hand, show a consistently younger age profile. Their p50 values cluster around 1–5 years, and even their p80 values often remain below 5–8 years, indicating fewer long-neglected objects (see “Normalized ROUTE object age distribution by category” plot above). The freshest datasets appear in LACNIC and JPNIC, where both medians and upper percentiles are very low, reflecting tightly integrated operational processes and regular updates tied to registry workflows.

Comparing both categories, authoritative IRR DBs clearly maintain more up-to-date information overall, with far less variance compared to many third-party IRR DBs. While TC demonstrates that a well-maintained third-party IRR DB can approach the quality of authoritative systems, the broader pattern shows that third-party IRR DBs are generally more prone to accumulating stale or abandoned objects, whereas authoritative IRR DBs maintain uniformly fresher datasets.

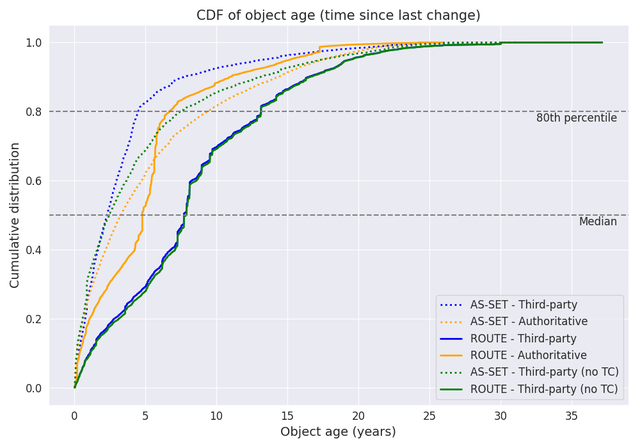

Next, we show the same data as a CDF, grouped by authoritative (orange) and third-party IRRs (blue). ROUTE objects are updated twice as often in authoritative IRR DBs, with a median age of ~5 years vs. ~7.5 years in third-party DBs. AS-SETs appear more frequently updated in third-party DBs due to TC, which holds ~20% of global AS-SETs. Excluding TC (green), whose relevance is mostly local to LACNIC (see previous article, “Global and local relevance of IRRs”), AS-SET update rates are similar across both IRR types.

As a fun anecdote (and because we can), we looked up the oldest ROUTE object in existence, which lives in BELL and dates back to 1988:

route: 129.97.0.0/16

descr: UWNet

origin: AS549

mnt-by: MAINT-AS549

changed: config@onet.on.ca 19881018

source: BELLHowever, the ROUTE object above is conflicting with more recent data in ARIN’s IRR DB.

The oldest ROUTE object that does not contradict any authoritative sources, is still routed, and even covered by a ROA at the time of writing also lives in BELL and dates back to 1993:

route: 142.164.0.0/16

descr: STENTOR6

origin: AS803

mnt-by: MAINT-AS803

changed: config@in.bell.ca 19930422

source: BELLAlignment with the Default-Free Zone (DFZ)

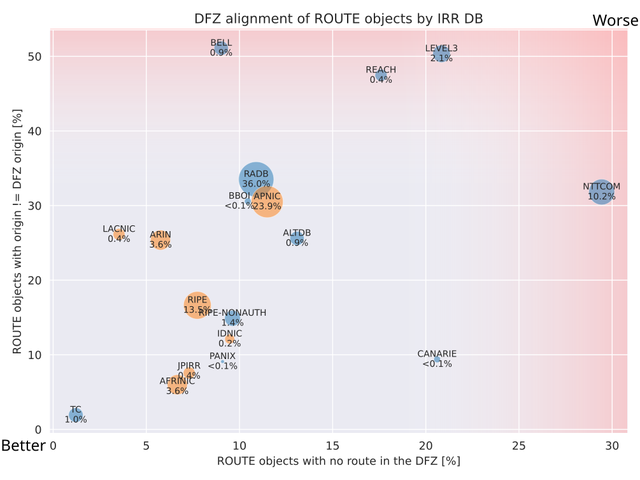

Next, we analyse how well ROUTE objects in various IRR DBs match the operational reality of the DFZ. The x-axis of the following plot shows the share of ROUTE objects with an origin different from what’s seen in the DFZ; and the y-axis shows the share of ROUTE objects without any matching route in the DFZ. Notably, some discrepancy with the DFZ is expected on both dimensions.6

The bubble size indicates each DB's share of total ROUTE objects. Bubbles closer to the bottom left reflect better alignment with the DFZ and more relevant data for the current state of the global routing table. Authoritative IRR DBs are coloured orange, third-party IRR DBs blue. ROUTE objects conflicting with RPKI are excluded, as some IRR DBs no longer return them in queries.7

Indeed, the authoritative IRR DBs of the RIRs are performing better in terms of data quality and relevance than most third-party IRR DBs. BELL, REACH, LEVEL3 and NTTCOM contain lots of irrelevant and/or conflicting information.8 RADB performs worse than any authoritative database, though APNIC is close. Interestingly, similar to the update frequency analysis, TC once again performs outstandingly well in our evaluation, because the maintainers enforce strict data quality rules on their users.

Conflict with higher-value sources

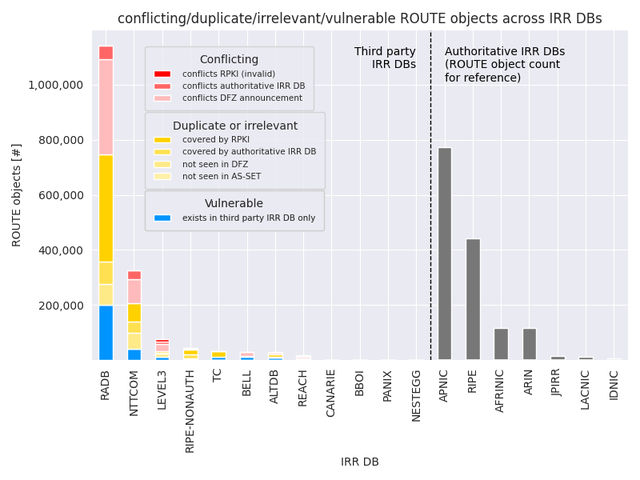

Last but not least, we assess ROUTE object data quality across IRR DBs by categorising them into three groups according to data quality problem indicators:

- Conflicting (red): Objects that conflict with more authoritative sources, e.g., RPKI invalids, newer conflicting RIR IRR records, or DFZ announcements with differing origins.

- Duplicate or irrelevant (yellow): Objects that are not observed in the DFZ or referenced by AS-SETs, or that duplicate information already covered by authoritative IRR or RPKI data. While redundant or unrouted objects are not inherently a quality issue, they indicate that these objects may be unnecessary or outdated.

- Vulnerable (blue): Objects found only in third-party IRR DBs but covering active DFZ routes; these are easy to hijack by claiming ownership in a different IRR DB.

Beyond their classification, ROUTE objects with these characteristics introduce tangible operational and security risks. Duplicate and conflicting objects, e.g., multiple records for the same prefix and origin across third-party IRR DBs, force operators to make arbitrary selection decisions, often biased toward newer objects. This undermines deterministic filter construction and increases the likelihood of accepting incorrect routing information. In the absence of authoritative IRR or RPKI validation, operators frequently fall back on observed DFZ announcements as a tie-breaker, effectively using the DFZ as an oracle. However, ROUTE objects that exist only in third-party IRR DBs and merely “validate” active DFZ routes are inherently vulnerable: they can be overridden or invalidated at any time by the injection of conflicting records in other third-party databases. This creates an attack surface where malicious actors can manipulate reachability without compromising authoritative registries. In contrast, ROUTE objects anchored in authoritative IRR DBs, especially when combined with RPKI, benefit from hierarchical trust and substantially reduce both operational ambiguity and exposure to routing attacks.

We discovered that different types of quality indicators often correlate, e.g., a ROUTE object conflicting an RPKI ROA often also conflicts an authoritative IRR DB entry and is not routed. Thus we also define an order of precedence of quality problems. For the previous example, the RPKI conflict has precedence over IRR DB conflict, because we assume RPKI is the most trustworthy source due to its cryptographic signatures. More details on the classification algorithm can be found in Appendix B.

Overall, ROUTE object data quality in most third-party IRR DBs - especially larger ones - is very poor. The vast majority are either conflicting, redundant with authoritative data, or not seen in the DFZ (which may -again- be legitimate). In RADB alone, out of ~1.2 million ROUTE objects, ~400k are conflicting and ~500k are duplicating official information and/or are not routed, with only ~400k of those backed by RPKI (dark yellow). Across all IRRs, over 250k ROUTE objects exist solely in third-party DBs and are routed in the DFZ, thus making them vulnerable to bogus injections, highlighting significant potential for abuse. Interestingly, we barely find RPKI invalid ROUTE objects indicating that if organisations care about routing security enough to create RPKI ROAs, they also seem to take care of IRR DB records.

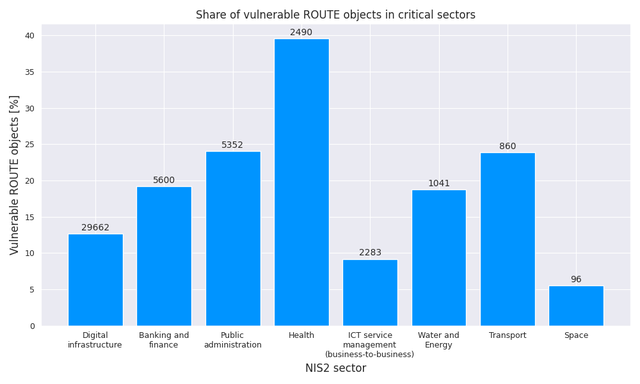

We continue by diving deeper into the blue, vulnerable part and quantify which infrastructures are behind these ROUTE objects, as these are in active use and particularly easy to hijack. Therefore, we map the prefixes of these ROUTE objects to critical infrastructures as defined by the EU’s NIS2 directive. A mapping was kindly provided by University of Twente and was also presented at RIPE90. The method is outlined in Appendix C. The results are presented below.

The distribution of vulnerable ROUTE objects varies significantly across NIS2 sectors. In absolute terms, Digital Infrastructure dominates with roughly 30k vulnerable ROUTE objects (out of ~235k total). However, looking at relative vulnerability, the Health sector shows by far the highest share (39.6%), followed by Public administration (24.1%) and Transport (23.9%). In contrast, sectors with a strong technical focus have notably lower vulnerability shares - Digital Infrastructure (12.7%), ICT Service Management (9.2%), and Space (5.5%). Overall, ROUTE object quality in critical sectors appears dependent on the technical expertise of its managing entities.

Takeaways

This article focuses on the data quality of the information on ROUTE / AS-SET objects stored in IRR databases globally. We summarise the key takeaways as follows:

- For ROUTE objects, authoritative IRR DBs are updated more frequently. Objects are typically refreshed about every 5 years versus 7.5 years in third-party IRR DBs.

- For AS-SET objects, authoritative IRR DBs and third party IRR DBs (without TC) are updated at a similar frequency.

- Authoritative IRR DBs align closer to real-world BGP announcements, while several third-party IRR DBs (notably BELL, REACH, LEVEL3, NTTCOM) contain large shares of outdated or irrelevant ROUTE objects.

- Many large third-party IRR DBs, particularly RADB, exhibit significant overlap or conflict with authoritative data and RPKI. In RADB alone, roughly 80% (900k) of all (1.2 million) ROUTE objects have quality problems or duplicate authoritative information.

- Over 200k ROUTE objects covering active routes in the DFZ exist only in third-party IRR DBs, making them vulnerable to misuse or hijack attempts. When mapping these to critical infrastructure, we find that technically mature sectors manage ROUTE objects more securely, while less technical sectors (especially Health and Public Administration) are disproportionally more affected.

- The IRR ecosystem remains fragmented and inconsistent. Authoritative IRRs and RPKI together form a much more reliable foundation for routing data. The only notable exception to this rule we could find is TC, which is relevant for the LACNIC region only and applies strict quality control on their IRR DB data.

The insights collected in this article begs the question: what would happen if we phase out third-party IRR DBs and only use authoritative IRR DBs and RPKI for generating BGP filters? We will evaluate this question in the next part of this series with real route server and traffic data from two major IXPs.

Notes

- All analyses are based on data collected on 2025-11-26.

- NIC.BR and NIC.MX do not provide structured exports and therefore we cannot include them in our analysis.

- RIPE-NONAUTH has a special status: while it is operated by RIPE, the database contains out-of-region objects that are not under RIPE’s authoritative control; usage is subject to constraints.

- In the near future, Autonomous System Provider Authorisation (ASPA) might help performing similar analyses for AS-SETs as well. At the time of writing, there are less than 100 published ASPA objects, which we consider too few to run a meaningful analysis.

- See NIST’s RPKI monitor (https://rpki-monitor.antd.nist.gov/), data retrieved 2026-1-16.

- It is common practice for ROUTE objects to exist without corresponding DFZ announcements. This enables their use at inter-AS boundaries (e.g., for filtering or peering purposes), and supports operational strategies such as temporarily announcing more specific prefixes.

- According to our tests with WHOIS, so far only RADB, NTTCOM and IDNIC do not return RPKI invalids anymore; we could not find RPKI invalids in RIPE-NONAUTH, TC and ALTDB to check whether they are returned via WHOIS queries. Notably, RIPE-NONAUTH has a cleanup mechanism for RPKI invalids.

- Note that this plot excludes NESTEGG, as it only holds two ROUTE objects, neither of which can be found in the DFZ, significantly impacting the readability.

Appendix A

IRR databases make highly diverse use of timestamp fields. The table below summarises the types of timestamps we have observed in active use. Note that the data contains some imprecision: an "x" in the table indicates that we encountered the corresponding timestamp in at least one object, not necessarily in all objects.

| IRR DB | 'Created' | 'Changed' | 'Last-modified' |

|---|---|---|---|

| AFRINIC | x | ||

| ALTDB | x | ||

| APNIC | x | ||

| ARIN | x | x | x |

| BBOI | x | ||

| BELL | x | ||

| CANARIE | x | x | x |

| IDNIC | x | ||

| JPIRR | x | ||

| LACNIC | x | x | |

| LEVEL3 | x | x | |

| NESTEGG | x | ||

| NTTCOM | x | x | |

| PANIX | x | ||

| RADB | x | x | |

| REACH | x | ||

| RIPE | x | x | |

| RIPE-NONAUTH | x | x | |

| TC | x | x |

Across all IRR DBs, there are three timestamp attributes in use: "created", "changed", and "last-modified". Standardised in RFC2622, the "changed" attribute records the date of the last change to the object and who made the change. This attribute is updated manually.

The "last-modified" attribute records the date of creation or the last change, however it is automatically generated. We identified two different use cases:

- IRRs using IRRd as their database include the automatically generated "last-modified" field, typically in addition to the "changed" attribute.

- APNIC, IDNIC, and RIPE no longer use the user-provided "changed" attribute and now only provide the "last-modified" attribute.

In addition, ARIN, CANARIE and RIPE also provide the automatically generated "created" timestamp, the date of the creation of the object.

However, the documentation is in many cases limited to the standardised attributes and does not cover "created" or "last-modified". Frequently, objects in IRR DBs supporting multiple of the timestamp attributes only use one. This presumably depends on the approach used to manage an object.

A special exception we identified for RADB is the date of their switch from IRRd-v3 to IRRd-v4. The import of objects to the new database resulted in no RADB objects having a "last-modified" timestamp older than 11/13/2023. We handle this issue by ignoring this specific combination during timestamp comparisons, falling back to the "changed" field.

Appendix B

For a better understanding of the ROUTE object quality plot in the “Conflict with Higher-Value Sources”-section, we provide an explanation of the different categories of ROUTE objects. Our classification walks the criteria below from 1-7) and applies the first category it can match. If none matches, category 8) is applied.

- ROUTE object "conflicts RPKI (invalid)" - there are covering RPKI ROAs for the ROUTE object; the origin in the ROUTE object is different from any existing ROA's origin.

- ROUTE object "conflicts authoritative IRR DB" - there are covering authoritative ROUTE objects for the ROUTE object; each of these has a different origin and one of them is at least 30 days newer than the ROUTE object.

- ROUTE object "conflicts DFZ announcement" - the ROUTE object is covering one or multiple announcements from the DFZ; the origin of the ROUTE object does not match any of the announcements.

- ROUTE object is "covered by RPKI" - there are covering ROAs for the ROUTE object.

- ROUTE object is "covered by authoritative IRR DB" - there are covering authoritative ROUTE objects for the ROUTE object.

- ROUTE object "not seen in DFZ" - this ROUTE object does not cover any announcement in the DFZ.

- ROUTE object “not seen in AS-SET” - the origin of this ROUTE object does not appear in any AS-SET

- ROUTE object "exists in third party IRR DB only" - any ROUTE object that does not fulfil any of the criteria in 1.) - 7.)

In many cases we found multiple categories to apply. Thus, the algorithm above implements an order of precedence, where an earlier match indicates a more severe problem (e.g., an RPKI conflict takes precedence over an unrouted ROUTE object, even though in most cases both will apply).

Appendix C

The EU NIS2 Directive (Directive (EU) 2022/2555 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2022/2555) regulates cybersecurity obligations for operators in certain critical sectors. These sectors are enumerated in Annex I, which lists the domains that the Directive considers critical for the maintenance of vital societal and economic activities.

The Directive does not include any technical identifiers, only lists economic sectors. For the technical analysis, these sector definitions are translated into categories that can be applied to AS-level data. The mapping from sector label to individual ROUTE object is done in four steps:

- General AS labels: ASdb is a curated database that assigns one or more semantic labels to each AS. These labels describe function, sector, or business activity.

- ASdb-to-NIS2-mapping: The labels provided by ASdb are manually mapped to the set of critical sectors listed in the NIS2 Directive. Though there are limitations due to the label granularity. Specifically, the categories Banking and Financial Market Infrastructure, as well as the categories Energy, Drinking Water, and Waste Water cannot be distinguished on an AS level and are therefore combined in this analysis.

- AS-to-Prefix: Using RouteViews pfx2as dataset, the labeled ASes are mapped to their announced IP prefixes as observed in BGP RIBs. It is important to note that critical infrastructure is not always fully represented in publicly visible routing data: many operational components, e.g., internal energy control systems or private financial networks, are not announced on the global Internet and therefore cannot be captured through AS-level observation. As a result, this step reflects only the Internet-facing footprint of operators, providing an indicator of externally visible critical infrastructure rather than a comprehensive or definitive enumeration.

- Prefix-to-ROUTE-object: Finally, the labeled AS - Prefix pairs are mapped to ROUTE objects by identifying the matching or closest covering (i.e., less specific) routes.

Through these steps, we connect critical operators to the IP space they announce, which is then mapped to the respective ROUTE objects, enabling the critical sector analysis.

Acknowledgments

This article was co-authored by Stavros Konstantaras (AMS-IX), Matthias Wichtlhuber (DE-CIX), Daniel Wagner (DE-CIX), Tobias Striffler (DE-CIX), Claudia Luik (DE-CIX), and Savvas Kastanakis (UTwente).

We would also like to thank Riccardo Stagni, Elisa Peirano, Tom Harrison, James Chirwa and Rene Wilhelm for their valuable input.

Comments 0