The 14th annual meeting of the Internet Governance Forum (IGF) will be running from 25-29 November 2019 in Berlin. Our staff at the event will be sharing key moments and takeaways from the sessions they attend. Check this page each day for the latest issues, arguments and ideas as they arise at the meeting.

29 November 2019, 16:30 UTC

Day 4: Independent Attribution of Cyber-attacks

With cyber-attacks an almost permanent fixture in news headlines, and with discussions between nation states on whether a cyber-attack can justify escalation "from cyber to kinetic", the question of attribution is clearly an important one.

A discussion moderated by Milton Mueller this morning looked at the idea, initially floated by Microsoft in 2016, of an independent "attribution organisation" for cyber-attacks. This would be a non-state actor modeled on the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

Milton started the session by saying that when they had looked at this a while back, the first thing they encountered were seemingly insurmountable issues of trust. The idea might sound great in theory, but many governments would object to participation from their adversaries, and the involvement of private companies like Microsoft would lead to questions about their relation to the US Government. So in many ways this appeared to be an Internet governance problem rather than a technical one.

Serge Droz, from ICT4Peace in Switzerland, said that attribution often required the kinds of intelligence that nation states gathered but did not like to share (for political considerations, or to avoid revealing capabilities). Nevertheless, many individual organisations would have pieces of the puzzle and there could be value in seeing how they fit together.

Last summer, they held a workshop (funded by the German Foreign Office) that looked at this issue. In attendance were people from the private sector, academia, civil society and governments. One of the conclusions (PDF) was that it might be better to focus on "fact finding" rather than making a final determination. There had been some debate on this point, but the view of government participants especially was that attribution was fundamentally a state activity.

But what are the value of facts in the post-truth era? Milton used the shooting down of MH17 as an example, noting that different actors used the facts surrounding the tragedy to support very different conclusions about what happened and who was to blame. He thought the value of such an organisation would be in producing a final determination.

And what do we mean by attribution anyway? Perhaps there two kinds: a "scientific" attribution that's about reaching a conclusion, and a second kind that is more like the determination made by a judge in a court of law. In the latter case, the judge has the authority to make a ruling, and perhaps the objections of government at the ICT4Peace workshop have some relevance here. On the other hand, maybe the key feature of a judge isn't so much their authority as the fact that they are independent from the parties involved. Of course, if we're talking about the anarchic world in which nation states interact and compete with one another in the absence of a higher authority, it can be harder to find the authority or independence needed - so this could instead resemble an arbitration process, perhaps managed via the UN.

At several points, attendees were reminded that this was not only about the attribution of state-on-state attacks. Such a body could also look at cyber-crime and things like botnets, and perhaps here it would be easier for governments to find common purpose. For the most part, people seemed more interested in discussing the former context.

A government speaker said that solving the question of attribution was crucial in light of ongoing discussions about the relation of international law to cyberspace - notably Article 51 in the UN Charter and whether cyber-attacks could justify "kinetic" responses. He noted that false flag operations that have been used in the past to justify attacks and perhaps cyberspace provides greater opportunities for this. They wondered if a third-arty could perform a kind of "escrow" function, which could rule on the validity of classified evidence without requiring it to be disclosed more widely. The key part was developing a mechanism that could be trusted.

Someone from the technical community reiterated that attribution was very hard. Any evidence would be incidental at best and easily falsified. Given that NATO had said cyber-attacks could warrant retaliation, the idea that you could attribute a cyber-attack to a single actor with absolute certainty was a dangerous one that could put people's lives in danger. A reply to this was that the level of certainty would probably scale according to the severity of the response. It was also noted that nation states had an interest in keeping this space nebulous, as it gave them opportunities to do things they would never do in physical space.

There was only one comment relating to IP addresses, when someone spoke briefly about the need to better map IP addresses against geographical locations. It was encouraging that Milton was able to point out that the relation of geography to technical identifiers was blurry at best, without the discussion becoming side-tracked. Perhaps this indicates that we are starting to move on from some of these more fundamental discussions.

29 November 2019, 11:30 UTC

Day 4: Trust and Security of IoT

A lot of ground was covered during this session. Frédéric Donck, ISOC, referred to the work of the Online Trust Alliance’s IoT Trust Framework. It gives recommendations to manufacturers and service providers on designing and managing their products throughout their lifecycle. The report outlines five minimum principles such as scheduling security updates, informing customers when the next security update is scheduled, implementing strong passwords and not using default passwords and having a plan for vulnerability management and privacy practice. The report also gives users, customers and distribution channels filters to assess privacy and safety and outlines for policymakers the necessary security and privacy principles for informed policy.

For those of you interested in software development aspects, check out ENISA’s Good Practices for Security of Internet of Things in the Context of Smart Manufacturing.

Another initiative worth taking a look at is the Bytecode Alliance, which tries to create new secure software foundations to allow application developers and service providers to run untrusted code. They try toincorporate security in all stages, while protecting personal and critical data and giving users the ability to delete their own data.

Merike Kaeo, ICANN Board/SSAC, cautioned that IoT devices can pose a challenge to the DNS. IoT devices use DNS to locate remote services or as a gateway to get services and if implemented incorrectly they can stress the DNS system. This can happen both by accident, for example if a lot of IoT devices come back on due to a power outage, or on purpose by amassing botnets to carry out complex DDoS attacks. She advised all popular IoT operating systems to make DNS’s security functions readily available and called for the development of a shared system allowing operators to share data on botnet activity. For further reading, check out SAC105: The DNS and the Internet of Things.

IoT is integrated in many high-risk devices such as smart transport systems, healthcare devices and so on. Marco Hogewoning, RIPE NCC, cautioned that, while a lot of attention has been paid to those devices, the security of light-risk, domestic devices has been largely ignored. Largescale attacks such as the Mirai botnet leverage these unprotected devices to undermine the core infrastructure of the Internet. He argued that something needs to be done urgently to address the presence of so many unsecure devices on the market and in our homes today.

Max Senges, Google, called for consolidation for the multiple efforts for IoT security. He talked of a long list of recommendations such as more government tools (such as coming up with security and usability labels similar to the nutrition labels of food products), more awareness raising and capacity building (for example making coding part of the official high-school curriculum), promoting independent testing, promoting security by design including human rights considerations, coordinating security updates, developing end of life plans.

Next, panelists discussed who should foot the bill for security. In many cases security testing can be expensive (think of having to crash cars for testing purposes). It is unlikely that manufacturers will voluntarily undertake this effort unless it is part of a certification scheme. Some cautioned that certification is not enough and sometimes something as simple as the maintenance system engineer’s laptop can introduce significant vulnerabilities. The room agreed that manufacturers should be accountable for what their products do. However, EU directives currently do not cover how long this liability should exist. And especially when we consider cheap devices, the lifetime of the device is sometimes longer than the lifetime of the manufacturer.

We debated for a bit on the role of consumers as well. Some pointed out that little is done to help consumers understand their IoT devices, and in some cases they don’t even know that their devices have IoT. On the other hand, a lot of consumers also don’t want to have to invest time in device security. Some asked: if a device is not secure and a consumer needs to take time and many steps to improve its security, should we even allow such a device on the market?

29 November 2019, 11:30 UTC

Day 4: More Cybernorms

Gergana wrote earlier this week about the some of the discussions on “cybernorms”, particularly those laid out in the recent final report of the GCSC. A workshop this morning, entitled Usual Suspects: Questioning the Cybernorm-making Boundaries, took as its starting point work on another set of norms, documented in the 2015 report of the Group of Governmental Experts on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security (or GGE), and specifically the norm which reads, “States should respond to appropriate requests for assistance by another State whose critical infrastructure is subject to malicious ICT acts.” (paragraph 13h).

The session was co-organised by APNIC, and was an explicit effort to bring policymakers together with operators and the technical community. The theme that emerged, illustrated by examples such as the 2007 cyber-attacks on Estonia (described by Merike Kaeo, who recalled the role of the RIPE Meeting in Tallinn in helping create trust and bring together expertise), the NotPetya cyberattack, and the Bangladesh Bank cyber heist, was that the language of norms developed through diplomatic processes can often be out of step with the reality of cyber threats and incidents.

Several speakers identified the issue at the heart of this - a misalignment of goals from the different stakeholder groups. For policymakers, norms are about preventing escalation of network security events to kinetic war. Whereas, as Olaf Kolkman noted, the goal of the self-identifying “technical community” is to keep the Internet safe and functional. And as Liam Neville, Assistant Director for Cyber Policy with the Australian government, pointed out - much of this work is being done back-to-front. Ideally, norms represent the codification of best practices developed over the long-term. The discussion of norms for cyberspace has been an attempt to kick-start that process, because the world simply doesn’t have time to wait for longer term evolution - we are trying to keep up with the speed that technology develops and reaches the population.

So the outcome? A call for greater awareness and understanding of different stakeholders’ priorities and perspectives, with national cybersecurity response structures (CERTs especially) well placed to help bridge that understanding gap. Not earth-shatteringly new, perhaps, but very much in line with the RIPE NCC’s advocacy and support for developing stronger national and regional Internet communities across our service region.

28 November 2019, 16:00 UTC

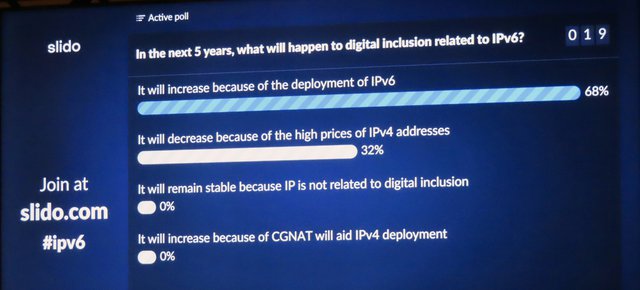

Day 3: IPv6 is About More Than a Protocol

If you’re reading this blog, it’s likely that you’ve heard the message before: we need to make the switch to IPv6 because there aren’t enough IPv4 addresses to keep up with the growth of the Internet.

What’s not as obvious are the more human-centric issues around the switch from IPv4 to IPv6. Who stands to benefit as networks deploy IPv6, and who is most likely to be excluded from the IPv6 Internet? It was these issues that an interactive and information-packed session titled IPv6: Why Should I Care? shone a light on, by getting participants to test their own assumptions about the effects of switching protocols.

The answers weren't obvious...and that was the point

As we learned, the answers depend on a number of different factors that aren’t immediately obvious, including users’ access (or lack thereof) to the latest mobile devices, the cost of IPv4 addresses on the secondary market (which itself depends on regional factors that differ across the globe), and existing infrastructure (e.g. is more of the population accessing the Internet via landline or mobile connections?).

Throughout the discussion, it became clearer than ever that IPv6 is crucial to maintaining a single Internet that can be accessed by the world’s entire population – not just the billions of users yet to gain access, but those who are already online.

28 November 2019, 11:00 UTC

Day 3: Splinternet?

Before the Internet, governments were used to having control over communications within their borders. It is then not surprising that some countries are still finding attraction in the idea of splitting off the Internet on their territory to be able to control and monitor its use. Reasons, spoken and unspoken, range from safeguarding sovereignty, protecting national security, ensuring independence and continuation of their systems in case of an international conflict and being able to control and restrict how their citizens use the Internet. Control attempts vary from building extensive firewalls, to trying to conglomerate all ISPs into one or even coming up with national versions of some popular apps like Facebook. Panelists discussed cases of connectivity being shut down as punishment for or to prevent demonstrations or to disrupt elections or riots.

It was interesting to hear from two Civil Society participants - Ephraim Percy Kenyanito and Kuda Hove - who highlighted some of the ways that governments in Africa are seeking to assert greater control at the infrastructure level. In Zimbabawe, the Government's national ICT strategy calls for reducing the number of incoming connections to the country from five to just one. The government in Burundi is taking a different approach - aiming to reduce the number of ISPs by making them responsible for content, thereby exposing network operators to greater legal and financial risks. It was noted that a "Great Firewall" was unlikely to be an option for most African governments, as this approach is expensive and requires advanced technical skills to properly implement and maintain.

An interesting comment was that discussions about network sovereignty often conflate the various network layers. Perhaps a more constructive approach would to properly identify which layer the issue sits on - many problems might be better addressed through interventions at the application or content layers. The protocol layer doesn't require much in terms of governance - we have an interoperable global network and we should seek to preserve this. Another comment was that while it probably wouldn't be helpful for policymakers to participate in protocol development directly, perhaps the IGF could serve to inform IETF discussions by highlighting their concerns.

Another commenter referenced the notion of shared protocols, such as TCP/IP, which ensure interoperability between a heterogeneous set of networks on the Internet. He proposed a similar kind of standards or protocols which could ensure "legal interoperability" between a similarly diverse set of policymakers with their own values, circumstances and challenges.

Speaking of values, one commenter argued today's Internet embodies US values that are not shared by the rest of the world. The greater priority that Europeans give to privacy concerns is a good example here. He argued that unless we can address this, not only is a splinternet inevitable - it will be necessary. The alternative would be lead to greater centralisation and surveillance of Internet users, which would be damaging to the open Internet.

Olga Kyryliuk, a Civil Society participant from Ukraine, said she'd heard many calls for dialogue at this IGF. This was all well and good - but this was the 14th IGF and now action rather than dialogue was needed most. She also pointed out that the nature of the IGF dialogue had moved quite noticeably from discussions of how "multistakeholderism would save the world" to the need for better collaboration to address the issues we are currently facing.

Olga Kyryliuk calls for combining the benefits of the multistakeholder model (bringing a variety of expertise and experience) and the multilateral model (bringing decision-making and enforcement power).

It is taking governments some time to realise the value a free and unrestricted Internet brings to societies and economies. Panelists raised the concern that even if governments only implement temporary policies of control or reverse them or only consider them without ever having implemented them, this already has an adverse impact on the use of ICTs. It creates apprehension and instils fear in the population. On a business level it creates an uncertain economic environment which discourages investment in ICT projects an infrastructure.

Panelists also discussed the need of discussions to differentiate between governance OF the Internet (tampering with how the Internet architecture or core infrastructure) and governance ON the Internet (managing how people use the Internet and what they do on it). While most strongly rejected the first, some viewed the latter is almost inevitable, due to cultural and legal differences around the globe.

- Gergana Petrova, Antony Gollan and Mirjam Kühne

27 November 2019, 18:30 UTC

Day 2: Arab perspectives on Digital Cooperation and Internet Governance Process

The Internet has been a very effective vehicle for digital inclusion and economic growth. The digital collaboration between stakeholders on a national, regional and global level is key to many of the solutions and innovations that help achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The United Nations Economic and Social Commission for West Asia (ESCWA) organised an Open Forum at the IGF to explore the opportunities to launch an Arab consultation to discuss the main principles, scenarios and architectures for a multistakeholder approach for better digital cooperation.

The Open Forum discussed the existing Internet governance platforms and venues across the Arab region. There have been a few attempts to develop national and regional Internet governance agendas in the Arab region, but they have not been sustainable and failed to preserve the stage. As an example, the Arab IGF with its current model, has not been able to meet the expectations and needs of stakeholders.

The panellists agreed that there is an urgent need to identify a new approach and structure that can ensure all stakeholders’ effective participation in a multistakeholder environment with concrete outcome.

The RIPE NCC re-confirmed its support to the existing IGF model and its values of inclusiveness, transparency and multistakeholder participation, while recognising the IGF's main challenges such as a lack of concrete outcomes and active participation from high-level policymakers and industry representatives.

27 November 2019, 18:00 UTC

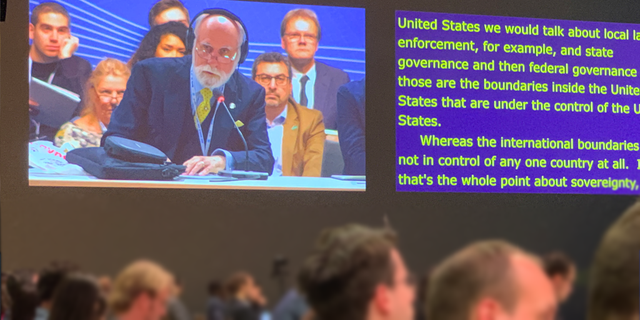

Day 2: Digital Sovereignty and Internet Fragmentation

There were so many interesting points raised, different perspectives shared and complex issues poked at during this session that it’s difficult to formulate a summary. So maybe I’ll just list some of the things that stood out most for me – I hope you find these as thought-provoking as I did…

- What is sovereignty even for, anyway? The protection of a state's citizens, or the state’s preservation of its own power? Sovereignty can - and is - used in different ways for different purposes.

- Sovereignty is anarchy on an international scale – this point was made by both session organisers William Drake and Milton Mueller and refers to what would happen (is happening?) if every nation tried to enforce its own national laws on international cyberspace.

- Drake argued that sovereignty is encroaching more and more into digital policy discussions and is often used as a trump card, as well as to stir nationalist sentiment.

- While Vint Cerf argued that the Internet was “born sovereign” because it was freely distributed for anyone to use, others questioned the outsized role that they see America playing in the global Internet

- Mueller argued that we need to abandon the notion of national sovereignty in cyberspace altogether, and treat it as a digital commons (much like nations have given up their rights to sovereignty in outer space).

- Xu Peixi pointed out that all states have their exceptions to the free flow of information: China with social stability, US with national security and EU with privacy considerations.

- Cerf argued that, just like we needed to homogenise things on a technical level in the early days of the Internet in order to make different networks compatible, we now need to homogenise our policies to be compatible in a shared cyberspace.

- Some people expressed concerns about capture when so much is concentrated in so few (mostly American) companies, which determine rules over content, make huge profits from advertising and data mining, and pay almost no taxes, etc. "Maybe to avoid the breakup of the Internet, governments have to break up some digital monopolies."

- One participant noted that many of the tensions mentioned above revolved around the application layer, and questioned whether it is technically possible to fragment the application layer while maintaining a single underlying infrastructure?

Like I said, a lot of different points of view – all of which added up to a fascinating discussion that left me wishing the session could go longer.

Vint Cerf participating in the debate about the Internet and sovereignty

27 November 2019: 16:00 UTC

Day 2: A Chance Encounter with the PIR Debate

Making my way between sessions, I stumbled across Brett Solomon, Executive Director of Access Now, leading an impromptu community discussion on ISOC's recent decision to sell Public Interest Registry (PIR), the not-for-profit company which manages the .org TLD, to Ethos Capital, a private equity firm that lists ICANN's former CEO as an advisor.

It was an interesting dynamic, almost like a mailing list discussion happening out in meatspace. A couple of ICANN Board members were at one end of the circle and a couple of ISOC Trustees at the other, taking turns to respond to questions from the crowd. It was hard to hear a lot of the comments over to the general meeting din, and the discussion had already been going on for some time before I joined. Nevertheless, I was able to catch a few fragments which might be worth sharing.

One question was how the non-profit .org community will engage with Ethos Capital in the future. At the moment, the community can engage with the "global" ISOC organisation, which is committed to serving the Internet community and has local chapters dotted all over the globe. This provides plenty of points that non-profits can interact with. Will Ethos Capital provide anything similar in terms of supporting open discussions on its operations? And is ISOC concerned by the way this decision - which appears to have taken everyone by surprise - is being perceived by the community?

Explaining part of the thinking behind the sale, the ISOC Trustees present said that the organisation's focus was on supporting the Internet - not running a business which might one day fail or fall on hard times. ISOC needs sustainabile and reliable funding to support its mission. Similarly, it's not certain that the Internet will always be centred around the domain name system. If things ever start to head in a different direction, ISOC might find itself in a conflict: its mission to support the Internet on the one hand, the fact that it relies on the sale of domain names on the other.

Summing up the feeling of the crowd, Brett said it was clear that the community wanted greater transparency from both ICANN and ISOC about some the thinking behind the decision and other specifics such as who knew what, and when.

As the discussion wrapped-up, Lynn St Amour (head of ISOC from 2001-2014), encouraged people to take a constructive approach rather than simply adding more fuel to the fire. She suggested the community should first seek clarity on what the actual problems were before rushing ahead with solutions.

ISOC has recently published an FAQ with some more information on this topic.

27 November 2019, 14:15 UTC

Day 2: Promoting Internet Standards

This session was a good continuation of the discussion earlier this morning at the Dutch embassy (see Marco’s section below). The motivation for this session was to see if the IGF can do more to promote Internet standards. The session started out with five recommendations:

- Create a (positive) business case for the deployment of Internet standards

- Incorporate Internet standards into law, that is regulated actively, so they can be deployed successfully

- Build Internet standards into products, so that they can be deployed successfully

- Make standards and their effects on Internet security better known

- Make ICT and Internet products more secure through education

The group split into five sub-groups to further discuss these overarching recommendations and come up with more concrete suggestions.

I participated in sub-group 3 where we discussed how to best ensure Internet standards are built into products (by default). We came up with points such as:

- Peer pressure and industry self-regulation

- Regulation and legislation (with some difficulty of course, given that the Internet is a global network and these products are manufactured and used globally)

- Governments should also be role models and use their purchasing power to “force” vendors to implement standards

- Financial incentives were also discussed, such as the discounts ccTLD operators/registries provide to registrars that deploy certain standards.

The results of the five different group will be collected and made publicly available on the IGF webpage.

27 November 2019, 13:15 UTC

Day 2: What Can we do to Increase Cyberstability?

Some two weeks ago the Global Commission on the Stability of Cyberspace (GCSC) issued its final report Advancing Cyberstability. We discussed their recommendations for state and non-state actors:

- Do something. Adopt and implement cyberspace norms that promote restraint and encourage action.

- Punish bad actors. Respond appropriately to norm violations, ensuring breaking the norms leads to predictable and meaningful consequences.

- Train yourself and others. Increase efforts to educate staff, build capacity and capabilities and promote a shared understanding of cyberspace stability. Take into account the different needs of various parties.

- Know what's going on. Collect, share, review and publish information on norm violations and their impact.

- Look into the future. Establish and support communities of interest to continue your work of ensuring stability in cyberspace.

- Respect diversity of views and needs. Establish a multistakeholder mechanism to adequately involve and consult everyone: states, the private sector, the technical community, civil society and so on.

And there are the norms for state and non-state actors:

- Don't break the rules of the Internet. Don't conduct (or knowingly allow) the intentional and substantial damage of the availability or integrity of the public core of the Internet.

- Don't break Internet infrastructure. Don't pursue, support or allow operations intended to disrupt the technical infrastructure essential to elections, referenda or plebiscites.

- Don't hack around. Don't tamper with (or allow the tampering of) products and services in development or production, if doing so may substantially impair the stability of cyberspace.

- Don't hijack devices. Don't commandeer the public’s ICT resources for use as botnets or for similar purposes.

- Disclose vulnerabilities. Create transparent frameworks to assess whether and when to disclose vulnerabilities or flaws. By default - disclose.

- Build and act responsibly. Especially if cyberspace stability depends on your products and services. Prioritise security and stability. Take reasonable steps to ensure that your products or services are free from vulnerabilities. Fix vulnerabilities and be transparent about them.

- Mandate basic cyber hygiene. States should enact measures (including laws and regulations), to ensure basic cyber hygiene.

- Don't attack. Don't engage in offensive cyber operations. Prevent such activities and respond if they occur.

If you are interested, have a read of the report. It's the culmination of three-years' hard work and provides a lot more background information and context.

RIR staff at the NRO booth

27 November 2019, 12:00 UTC

Day 2: Carrots or Sticks?

Or as we learned this morning, in German: "Zuckerbrot und Peitsche". The conversation was about how to incentivise different stakeholders to implement and make use of Internet standards that can make the net a safer and more secure place. Using the momentum of the IGF, and ahead of a bigger session on this topic later in the afternoon, we were invited to a breakfast session at the Dutch embassy here in Berlin where we met with our German peers from the public and private sectors. The idea was to share our experiences in encouraging people to adopt a wide range of technologies, from IPv6 to DNSSEC and DMARC.

The RIPE NCC participated in this as one of the partners in the Dutch "Platform Internetstandaarden", but of course also because we have had opportunity to see up close how many other countries and communities in our service region approach this problem space. It was good to see that from the German side, some of our long-standing partners like DENIC and ECO joined to share their experiences.

From the Netherlands, driven by public-private partnerships, we again highlighted the usefulness of the https://internet.nl toolkit in allowing people to measure their progress meeting various standards, but also how these measurements can spark a competitive drive for organisations that want to do better than their peers. This is something we see among the different Dutch city councils, an example that was presented at RIPE 79. From the German side, we learned the approach they took with implementing DANE, motivating operators to implement in order to comply with standards developed by the Federal Office for Information Security.

The discussion provided ground for further cooperation between the different parties, but also stressed that not everything can be copied one-to-one. For instance, the example where SIDN (.nl registry) incentivises registrars to enable protocols such as DNSSEC and IPv6 by giving small discounts on the registration fees. It was interesting to learn from DENIC that while they were unable to implement a similar scheme, they did notice some cross-border effects, where Dutch registrars now also sign their .de domain registrations. This was an effect they also saw from Danish registrars after the .dk registry began requiring the use of DNSSEC for their domains.

A bright and early start, but it was certainly worth leaving the IGF venue for a bit.

26 November 2019, 20:00 UTC

Day 1: Making Life Easy for SMEs?

Today, approximately 85% of all companies are Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). What sort of challenges do they face when it comes to taking full advantage of modern technologies and entering digital commerce? A quick summary of main points discussed:

- Increased accumulation of power in the hands of a few international conglomerates stifles competition. In addition, the data these mega-companies accumulate gives them an undeniable advantage in market research, tailoring advertisements, adapting products, and so on.

- The unstable regulatory climate is a source of uncertainty. Some countries are considering taxes on data. In addition, SMEs worry that if regulation goes into too much technical detail, it risks stifling innovation. Big companies have easier access and influence on governments than SMEs.

- Data ownership needs to be returned to the entity where the data originated from, rather than assigned to the entity that collected the data, in order to further incentivise innovation.

- Data dependency on big platforms makes SMEs vulnerable should those ties be suddenly severed. Even if this happens by mistake, the process to restore relations/services can be cumbersome and lengthy, often with severe consequences. Some panelists called for the establishment of decentralised, self-managed data platforms.

- Transformative technologies like IoT, AI, blockchain and 5G might propel some SMEs to great success. That said, the panel doubted that the majority of "mom-and-pop shops" would be able to take full advantage of them until much later in the game.

- Lack of skills and education continues to be a big barrier to entry. Institutions such as the ICC are looking to establish platforms offering SMEs the tools and knowledge to engage in international e-trade.

RIPE NCC staff interviewing different IGF participants to hear their perspectives

26 November 2019, 18:30 UTC

Day 1: The Future of Internet Governance

As Chris already mentioned in the first post on this liveblog below, this feels like a crucial moment for Internet governance, the IGF, and figuring out where it all goes from here.

Despite this being the fourteenth IGF, the fact that it’s the biggest to date, and that Angela Merkel spoke during the opening ceremony, a lot of the discussions taking place at the highest levels are fundamentally existential in nature.

Indeed, the UN Secretary General even convened a High-level Panel on Digital Cooperation last year to look at the future of Internet governance and what truly global digital cooperation might look like.

The discussion around the UN panel’s report, which sets out three possible models for digital cooperation going forward, focused almost exclusively on the "IGF Plus" model – perhaps not surprising, given that it was being discussed at the IGF, although this is the model the panel has most fleshed out and there seems to be a genuine desire to build on the successful aspects of the current IGF while at the same time addressing its shortcomings. You can learn more about the panel’s report and the RIPE NCC’s response to it in this RIPE Labs article.

One concrete suggestion was to appoint an official liaison to the IGF’s Multistakeholder Advisory Group (MAG) who would attend as many of the Internet governance fora as possible – although, with more than 110 national and regional Internet governance initiatives globally, it seems like a bit of a Herculean task. (One of the RIPE NCC’s responses has been to highlight the value of such initiatives along with the need to channel their outcomes into any potential future IGF Plus model.)

The idea of “social digital platforms” was another idea that came up both during the UN panel session and another session on the future of Internet governance, where Tim Berners-Lee suggested the need for a kind of “Wikipedia” for political debate – a centralised, accessible platform where a civilised debate can take place around governance issues.

Göran Marby, ICANN’s CEO, went as far as to say that we have yet to even clearly identify the problem, let alone the solution, when it comes to regulating the Internet. “No one owns it, and everyone owns it,” he said. “How do you regulate that?”

The prevailing feeling seemed to be this: even though the Internet is now considered by a large percentage of the world’s population as being essential to their daily lives, the truth is that no one has really figured out how to govern it.

To make matters even more difficult, of course, “the Internet” is a moving target as more and more of our data exchanges, economies, social interactions, education, government services, etc. etc. move online. At the same time, this massive online migration makes the need for good governance even more urgent.

26 November 2019, 14:30 UTC

Day 1: One world. One net. One vision.

Reminding us of this year’s IGF vision - “One world. One net. One vision.” - Dr. António Guterres, Secretary-General of the United Nations, addressed a room of more than 2,000 delegates to officially open the event. He spoke of the world’s collective responsibility to give direction to new technology, to make it more equal, safe and secure. The attitude of trial and error of the private sector contrasts with the public sector’s propensity to tread carefully and conduct thorough consultations before acting, resulting in a regulatory gap. The absence of technical expertise among policy makers only exacerbates the problem.

Dr. Guterres called on the world to unite under one vision to prevent the fracturing of the Internet, to increase representation of women in the technology sector and entrepreneurship more generally, to combat the unequal distribution of knowledge, and to safeguard privacy and other human rights in cyberspace. He cautioned against turning a blind eye to the low-intensity cyber-conflict that has become a part of our reality today, which is undermining trust and deepening the political divide as it becomes more severe.

Here are the three ways the Secretary-General proposed to pave the way forward:

- Government representatives from all over the world, along with experts from business and civil society, should use the IGF as a platform to share perspectives and agree on norms, and then bring those ideas back home.

- The UN High-Level Panel on Digital Cooperation should explore a global commitment to digital trust and security and agree on global norms.

- The Secretary-General will appoint a technology envoy to work with governments, businesses and civil society to support the concept of a shared digital future and bridge the digital divide.

Speaking in the context of the recent 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, Dr. Angela Merkel, Federal Chancellor of Germany, drew parallels with the division this wall represented and warned of the danger that similar divisions might re-emerge today. She called on people all over the world to protect the freedoms we enjoy and never to take them for granted.

The Internet performs a core function in our global economy and is a vital place for democratic discourse. For some non-democratic states and even some private companies, the freedom the Internet offers is an irritant. Noting that the term meant different things to different people, she said that "digital sovereignty" did not mean protectionism or censorship. Digital sovereignty needs to be balanced against locking people and populations out from the rest of the global community. She said that attacks on Internet connectivity have become a dangerous instrument of politics, which deprived people of their basic rights to access information and communicate. We need to preserve the core of the Internet as a free public good. We need to act multilaterally to arrive at a common understanding of an open internet and keep in mind that not everything that is technically possible is ethical or desirable.

Dr. Merkel also warned against interacting only with people who share our own opinions. She applauded the IGF for bringing different stakeholders together to promote a common understanding of their values and goals for the future, which in turn was key to the creation of a global consensus for a free, open and decentralised Internet.

A lot of powerful words. And perhaps for a lot of us tech-folks it might seem like political talk. The bottom line for me is that it will take courage to engage with people who don't understand of share our views. But there is no way around it - we have to do this if we want to preserve the Internet as the wonderful globe-spanning force it is for our generation.

26 November 2019, 13:00 UTC

Day 1: ICANN Session: A Few Comments on DoH and PIR

This morning I attended the session focusing on threats and opportunities for ICANN and the ICANN Board in the (near) future. In the open mic session, someone asked if the ICANN Board had any recommendations on new technologies, mentioning DNS over HTTPS (DoH) as an example.

David Conrad (ICANN) responded that DoH in itself was only a protocol. The interesting part was in how to deploy it. This discussion is currently taking place in a number of venues, most importantly in the IETF. ICANN doesn’t really have an opinion about the protocol specification, however he pointed to a paper that he and his team had published on the ICANN website. He did acknowledge that there could be a shift in how the DNS operates for the end user depending on how this was implemented.

There was also a discussion about the need for policymakers to get involved in technical discussions and possibly also at the IETF. David said that yes, policy makers should be involved - but perhaps not at the level of protocol specification (at the IETF). They should definitely be aware of the potential implications of the implementation of these protocols and involved at that stage, however. He further explained that two of the three current implementations do not limit operators who want control over their DNS operations. The third does change control planes, and this is the one that Mozilla has implemented.

There was also a comment about the transfer of the .org registry and the fact the Public Internet Registry (PIR) was now a commercial company. David suggested that people interested in this topic review not only the recent discussions, but also some of the history, including the agreements from the time of the original bid. The speaker said she remembered that this was closely tied to being a public service for the good of the Internet. She emphasised that this transfer not only concerned ISOC, but would affect the larger community and she thought this was something ICANN should also discuss.

26 November 2019, 12:30 UTC

Day 1: A Precarious Balance

The introductory session on security and safety opened with an insightful discussion with Tobias Feakin, the Cyber Ambassador for the Australian Government. He talked of the difficulty governments face around the world balancing privacy with security. First, while governments want to allow a lot of flexibility to platforms, absolving them of all responsibility (to the extend of having absolutely no idea what the platform is used for) is not acceptable. Second, he reassured the audience that governments realise that breaking encryption or forcing companies to build backdoors would have a crippling effect on their economy. This is why they try to take measures that are proportionate, reviewed by independent processes and mindful of human rights and business concerns. He added that governments follow legal process, which they are always looking to improve further. Lastly, he admitted that many governments are not good at communicating well about their policies: exactly what the policy entails, how the policy was agreed on as well as the check and balances that are in place.

Next, we broke out into six groups, bringing back some interesting points:

- The Human Rights group acknowledged the difficulty of putting in practice different policy objectives. They underscored the need to focus to the end user – to educate them so they understand how their rights are affected and empower them and to act. They also talked of the responsibility of the private sector to not only delete offending content, but to aid the public sector in bringing the perpetrators to justice.

- The Security group cautioned that in many cases governments do not understand the technical core of the Internet and what is technically implementable. They also encouraged them to attempt to measure security compliance.

- The Ethics group underscored the need for clearer, internationally standardized definitions, while acknowledging that these might need to be adapted or localised to fit regional understandings. They also called on companies to proactively share their code of ethics.

- The Stability and Resilience group signaled a few important technological developments. First, the runout of IPv4, leads to a higher operational cost of these addresses, which in turn results in higher barriers to entry for new Internet businesses. Second, the slow deployment of IPv6, its poorer interoperability and peering, risks creating two Internet "islands". Third, the centralised DNS distribution makes it an easy target for hackers. And fourth, DoH’s change of control away from the service provider to the application provider, leaves users in the difficult position of having to search for legal recourse in jurisdictions across the globe.

- The Technology group spoke of the importance of developing a playbook addressing concrete questions such as cloud resiliency, data access and localisation.

- The Safety group called for the need of reliable and robust data source on cyberincidents, cautioning that media only reports on some, not all cases. They also highlighted the distinction between risk and harm and the need to balance any security measures with the freedom of expression, especially that of vulnerable populations.

26 November 2019, 12:00 UTC

Day 1: In Memoriam: Jimmy Schulz (22-10-1968 — 25-11-2019)

I first met Jimmy in the run up to EuroDIG 2014, in typical Internet fashion over a dinner after a planning meeting. It was clear from the onset he knew what was going on and understood the Internet Governance ecosystem like no other. I know there are other politicians who are active in this field and understand the multi-stakeholder approach, but to find people which so much experience still is somewhat rare. And in typical Internet fashion, as we left the restaurant, it was Jimmy who suggested we take a cab, because he knew a bar that was still open. Of course, he knew Berlin, but little did we expect that we would actually end up in little know, members only hang out underneath the German parliament. The groundwork was laid and EuroDIG 2014, in Berlin, was a success. But it wasn't the big one, it wasn't the global Internet Governance Forum.

Here we are, back in Berlin again, with the Internet Governance Forum about to start. Many people had a role in convincing the German government to help IGF by hosting one of their meetings. Jimmy, as a member of parliament, was instrumental in these efforts. But it certainly wasn't his only achievement. With the Internet now being a big political topic, I always felt somewhat comfortable that there was at least one person in the German parliament, that I was sure who understood the ecosystem and would steer the discussion in the right direction.

Even over summer, Jimmy and his staff remained committed to make this a success. Writing letters to parliamentarians all over the world, to invite them to Berlin and encouraging them to join the global debate about Internet Governance. Somewhat surreal to learn, a day before the start, that he has passed.

Farewell my friend, the world needs more people like you.

25 November 2019, 20:30 UTC

Day 0: GigaNet's Research

Every year, GigaNet, the network of academics focusing on internet governance, present their latest research at their annual symposium.

Intermediaries

First, we looked at intermediary liability, an issue discussed by a few RACI attendees at RIPE Meetings as well. A system requiring a judicial ruling (where an intermediary can only be held liable for third party infringing content if they fail to take it down in the face of a judicial order telling them to do so) allows for greater freedom of expression (intermediaries won't over-block content due to fear) and fosters innovation (it provides online companies with legal certainty to experiment with different business models). However, researchers caution that courts are not designed to anticipate the systemic effects of their judgements, nor are they best fit to define the technical conditions for liability.

This leads to an interesting question: can you sue platforms to reinstate content? This depends on your country’s regulations (for example, if platforms have a duty to treat users equally and provide equal access). You might also find yourself having to prove that said platform is essential infrastructure for speech. Read here for more tips, although spoiler alert – you might be out of luck if you're in the US, as no successful reinstatement claims have been won via the courts so far.

Rift Between Countries

Few can deny that in many cases, implementing technical standards has political consequences. The people who attend technical meetings such as the IETF and RIPE (the latter not explicitly mentioned in the paper) shape these standards and influence both the technical and political operation of the Internet. It’s been found that the current distribution of leadership positions and information patronage in many technical fora prevents developing countries from fully participating, even as they are increasingly catching up economically. The authors caution that countries like Brazil, China, India, Iran, and Russia can become disillusioned due to the perceived Western bias and advocate for intergovernmental forms of Internet governance.

You might remember Ilona Stadnik's talk on the sovereignisation of the internet in Russia at RIPE 79. At the IGF, she presented the research she is working on right now concerning the US-Russian rivalry for setting global cyber rules. In 2017, the UN GGE failed to reach an international agreement due to political tensions, including for example whether international law should address issues of information content (the infosecurity model advocated by Russia) or only network infrastructure (the cybersecurity model advocated by the US). In 2018, the two countries formed the OEWG and the GGE respectively, each with the goal of establishing global cyber-norms. We'll have to wait and see. Will their final reports (due in 2020 and 2021) show any joint collaboration, or will we end up with two sets of "global" cyber-norms?

Some researchers have cautioned against simply copying norms and best practices from developed countries to developing ones, as a lot of the assumptions (about human rights, freedom of expression, privacy, and security) on which these norms and practices are based might clash with the political reality of developing countries.

The Need for One Global Solution

So, should we have different sets of cyber-norms? Er, no. Here we have a paper cautioning against nations having different policies at a regional level to solve what is essentially a global issue. It calls for more cooperation between law enforcement and the security communities on a global scale, more transparency by manufacturers and service providers on the security of their products, greater awareness of the security risks, as well as understanding of the individual responsibility of each actor in the supply chain, all the way down to the users.

Privacy, Disinformation and More

There are a lot more papers that I cannot cover in the short space here. For those of you interested in more legal matters, check out this paper arguing that the current GDPR framework does not sufficiently allow self-protection of one's data or this one outlining the different regulatory approaches taken by 13 different countries to combat disinformation.

A very cool and very large mural made from tape!

25 November 2019, 19:00 UTC

Day 0: Overcoming Barriers to Meaningful Participation in the MENA Region

It is well known that a country’s successful development depends on having sufficient capacity. While financial resources and technology are vital, they are not enough to promote sustainable Internet development. Without trained and skilled people, countries lack the foundation to plan, implement and review their ICTs national strategies including Internet development and its services.

RIPE NCC, ISOC & NTRA Egypt co-organised a Pre-event at day zero at IGF, inviting distinguished and diversified speakers to share insights on some of the most relevant efforts and experiences relevant to the capacity building in MENA region.

The agenda of the pre-event included two sections where the RIPE NCC contributed to the one focused on “Regional Engagement and Capacity Development Efforts”.

The speakers highlighted the priorities in capacity development in the MENA region, including the skills gaps that needs to be filled and best ways to deliver training as well as the role of the different organisation in the region. ICANN, ISOC, RIPE NCC and ITU-D showed their willingness to continue their joint-efforts in delivering capacity-building activities in the region on the areas that they are working on.

As a Regional Internet Registry, the RIPE NCC supports the Internet infrastructure in our region through technical coordination, and training and capacity building is a big part of this. By keeping this at the heart of our mandate and functions, we respond to the increasing demand for technical support at the national and regional levels in our service region.

25 November 2019, 11:00 UTC

Day 0: Welcome

The annual Internet Governance Forum (IGF) again fires up this week, with more than 5,000 people pre-registered. The 14th instalment (this time in Berlin) promises to be the largest IGF yet, held at a key moment for many of the issues known collectively as “Internet governance”.

The perennial challenge for Internet governance is how diverse a subject it is - the IGF schedule has traditionally reflected this with a dizzying array of workshop and plenary sessions spread over a week. While the Multistakeholder Advisory Group (MAG) responsible for guiding the IGF’s development and agenda has made efforts to constrain the number of sessions in recent years, the programme is still very heavy (and that’s before you even consider the many side meetings).

It’s been apparent for many months that this would be a significant IGF in terms of discussing the future of Internet governance itself. The UN Secretary-General’s High-Level Panel on Digital Cooperation and its recently published report, The Age of Digital Interdependence, have laid the groundwork over the past 12 months for a serious reconsideration of how we approach Internet governance at the global level and the form of the IGF itself. This included a number of quite specific proposals for what a global Internet governance structure might look like going forward. Numerous sessions over the course of the week will touch on this, including an intervention from the UN Secretary-General himself at the Opening Ceremony on Tuesday.

At the same time, recent months (and even recent days) have seen the temperature rising in relation to some of the most bitterly fought arguments in Internet governance, including the role and responsibility of social media platforms, trust and transparency in global Internet administration, or the role of governments and the UN when it comes to cybersecurity. Even for a community like RIPE, which is strongly associated with the underlying Internet infrastructure rather than the content delivered over that infrastructure, these are worrying flash points, with stakeholders searching for potential solutions at all layers in the stack.

As the RIPE community approaches its own historic moment, with the exhaustion of the IPv4 address pool, the importance of an open and multistakeholder venue to discuss these issues is clear. At the same time, with different stakeholders groups vying for control and legitimacy, the sustainability of the IGF itself is far from assured.

This week, the RIPE NCC will have a number of staff following the discussions in Berlin, and we plan to post real-time blogs, focusing, where we can, on the relevance for the RIPE community and the global registry system. Meanwhile, we’d love to hear any feedback you might have on these discussions, and if you’re at the event in Berlin, please come by the NRO booth in the IGF Village and say hi.

Comments 0

The comments section is closed for articles published more than a year ago. If you'd like to inform us of any issues, please contact us.