A critical pillar of a sustainable digital economy is circularity. A circular digital economy will entail a production and consumption model for IT hardware that minimises the amount of resources used while maximising life cycle longevity. But one of the greatest obstacles to realising circularity within the IT sector is economics. Originally published on the SDIA blog, this article seeks to address how to move the sector forward on its journey to sustainability via business model innovation.

Key Points

- Transforming information technology (IT) hardware to a service that cloud and infrastructure providers use can open new pathways to circular economic models, but will require a business model that is aligned with the needs and challenges of the 21st century.

- IT Hardware-as-a-Service will be the only way to reach circularity in-line with economics, as the hardware will remain property of the manufacturer or a third-party service provider so they have a natural incentive to extend the lifetime of it, repair, and refurbish.

- Such a model will have countless benefits, not least of which will be for producers, consumers, communities impacted by supply chains, and the planet.

- There will be challenges to overcome, but this new kind of “Sustainability-as-a-Service” model is meant to address areas where existing models fall short.

Last month was a busy one for sustainability. In addition to presenting a lightning talk on the subject at RIPE 83 and publishing a post on RIPE Labs dispelling myths about hardware refurbishing, I was able to deliver a keynote address at the Open Compute Project’s (OCP) Future Technologies Symposium on 8 November as part of the 2021 OCP Global Summit. As part of that keynote, we – the Sustainable Digital Infrastructure Alliance (SDIA) – outlined our vision for how to accelerate the adoption of circular business models in-line with our Roadmap to Sustainable Digital Infrastructure by 2030.

As I noted in the original text, since the advent of the commercial Internet in the 1990s, the dominant model for IT hardware has centred around the need to adopt improved technology to keep up with growing demand, increase performance, and meet customer expectations. In a world that has become so dependent upon digital technologies, outages not only impact the bottom line of the company tasked with maintaining digital infrastructure, but can disrupt vital communications channels, business activity, and modern life as we know it. As such, guaranteeing both performance and reliability at a competitive cost has, understandably, been one of the greatest motivators for hardware providers over the past 30 years.

Of course, when IT hardware was significantly improving from one cycle to the next, the reliability gained via performance and efficiency improvements that new hardware offered made sense from a business point of view. Yet, despite rapid developments in the hardware sector, little has changed in the way we procure and utilise servers, fuelled by both inertia and complacency. An operator purchases them for three-to-five years with a service contract; after the service expires, most companies simply buy new servers. In turn, the old ones are discarded, shredded, and recycled, or in few cases refurbished, but typically with a low resale value.

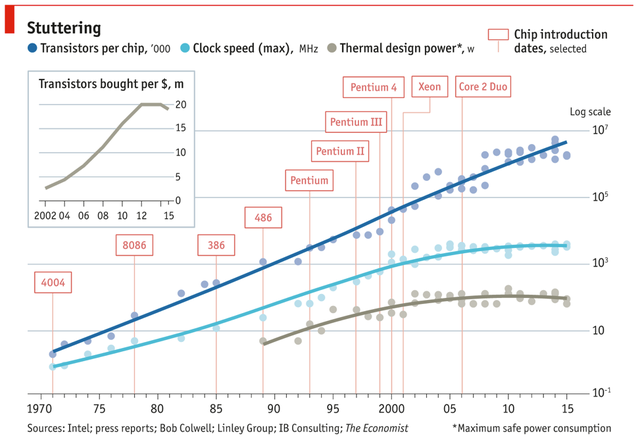

One of the most overlooked and problematic aspects of this model, however, is the resource consumption of digital technologies and their impact on the environment. Bearing this in mind and considering the recent deceleration of Moore’s Law as well as the generational performance improvements of servers - e.g., two-to-three times every two years - having long faded, why have upgrade cycles not been prolonged as well?

The Problem with Servers: Where Do We Stand?

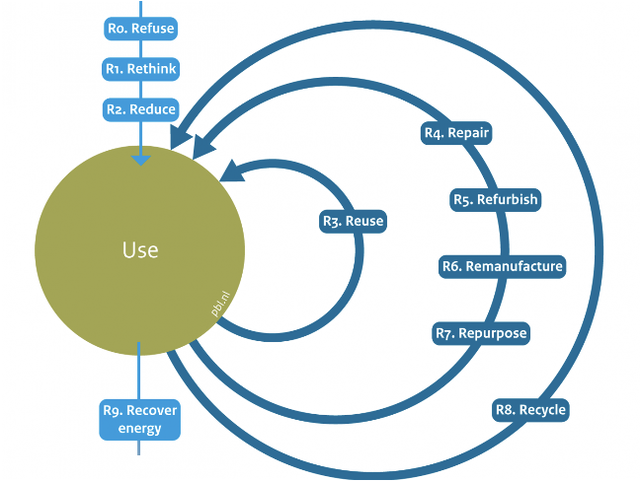

Like with much of our contemporary economic models for goods, ranging from clothing to computers, this is referred to as a linear model, where the result of the natural resources used to create the product ultimately end up as waste. Contrast this with a circular model, one that minimises the amount of resources wasted while maximising life cycle longevity of a product as a useful resource. Even though the latter model is better in practically every way and must become our economic model going forward, it faces significant obstacles, including the prominent business models in use.

When it comes to the digital economy and IT hardware in particular, the truth is that most original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) have built businesses around the three-to-five-year upgrade cycles, ones that rely on the customer replacing their equipment regularly. Despite failing to embed sustainability into the core of hardware design, this paradigm worked for both customers and vendors from an economic perspective for as long as the performance gains from each upgrade were significant. To further support this model, many manufacturers stop supporting the firmware of older hardware – a practice known as premature or planned obsolescence – to essentially force customers to upgrade to a newer model. If they choose not to, a customer runs the risk of running equipment with outdated and or unsupported software, a practice that is especially common among networking and server equipment.

But now the world is changing. Performance increments are not as noteworthy – hardware improvements have plateaued, for instance – and customers are demanding more sustainable solutions. Moreover, hardware that is more modular, repairable, and lasts longer can be serviced better, and can better incorporate environmental externalities when factoring in the overall footprint of a product, such as carbon dioxide emissions and resource extraction/use. This is not only important for helping customers make more sustainable choices, but it goes hand-in-hand with new policy and regulation that is requiring OEMs to provide better repairability, offer longer support for firmware, provide greater transparency, and make sustainability a key part of a product’s life cycle (e.g., the European Union’s Circular Economy Action Plan and Ecodesign Directive for repairability).

Yes to a Circular Economy – But How?

One thing is abundantly clear: the aforementioned upgrade cycles and ever-increasing number of new servers having to be built to fuel the top-line growth of the OEMs will not lead to a circular economy. For that, we have to radically rethink the business model. There is still a business in hardware, a profitable one, but it will look different. Furthermore, the key to unlocking a circular economy for IT hardware lies in transforming previously perceived threats into exciting, and lucrative, opportunities.

It all begins with the ownership model. As long as the OEM/vendor is selling the product to the customer and the customer is owning the product, what is the incentive for the OEM/vendor to make a product that will last for a longer period? The longer the product lasts, the longer it will take for the customer to come back and buy a new product (which creates top-line revenue for the OEM). This is the prevailing business model for many consumer electronics (think smartphones or laptops), but is just as applicable to IT hardware (such as that used in large-scale, enterprise settings like data centres). While it may have benefited producers and consumers alike, it has led to dire consequences for both the environment and communities around the world such as those facing the local impacts of mineral mining or electronic waste (e-waste) dumping.

Add to this the fact that global supply chains are facing massive, unprecedented shortages that will not likely subside anytime soon, which are placing significant pressure on chip and hardware manufacturing in particular. In the face of supply shocks despite sky-high demand, our relationship with our planet’s finite resources – ranging from copper in Zambia to water in Taiwan – is already leading toward a circular north star.

According to ITRenew President Ali Fenn, the global chip shortage is driving more companies to source second-hand hardware for their data centres – so much so that hyperscalers’ decommissioned gear “flies off the shelves as soon as it’s available.” EmXcore – the Amsterdam-based hardware refurbisher that I wrote about previously – further corroborated Fenn’s insight, underscoring to us that they have seen an uptick in demand for the refurbished and reused enterprise hardware they offer. And with tools like those offered by Interact, it is becoming even easier to identify old and inefficient servers and replace them with refurbished or reused ones. In other words, if the existing business model does not follow the headwinds, it may well likely be forced to change due to the changing nature of supply and demand.

Transforming Novelty Into Opportunity

But what if the vendor or even, say, a third-party service provider were the owner of the product? And instead, they provided the resulting digital power, consisting of the networks, computational processes, and data storage capacities as-a-Service, in the same spirit as Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) and Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS)? Then the vendor or service provider would have a clear incentive to maintain, repair, refurbish, and extend the lifetime of the hardware as long as possible, and the customer would have insurance that they will get the consistent capacity and digital power they need. It would also turn repairability, long-term service provision, and sustainability into foundational components of IT hardware.

Although this may seem like a daunting change, modifying the business model of IT hardware OEMs and vendors would have myriad benefits for all stakeholders involved – not just the producers and consumers, but also communities impacted by supply chains as well as the planet. It is also not a completely new idea; the model already exists in a similar form for other businesses (think of car rental companies, for instance). It also has the opportunity to create new business opportunities as well, such as for the vendor itself, certified third-party repair specialists, and licensing. The last one is particularly relevant if an OEM would rather outsource maintenance to specialised firms and instead build on the benefits of scale in the maintenance and replacement of computers to diverse users. Such service providers would be able to efficiently manage a large pool of hardware, where durability, maintenance, and efficient allocation would bring benefits to all stakeholders in the hardware business as well as great environmental benefits.

In our view, the IT Hardware-as-a-Service model would open a whole new world of flexibility and potentially even more business for hardware vendors, not to mention provide a scalable alternative to any OEM interested in more sustainable solutions. But what if a customer needs to scale down? That poses no problem; they can, and the hardware is simply used for another customer. After all, what is limiting the growth of more cloud providers and new compute-intensive businesses? The answer is easily the cost of hardware! An as-a-Service model would clearly address this, while also potentially helping to alleviate conflicts within primary, secondary, and other markets and increase competition given that consumers would significantly benefit from such developments.

The Challenges: Accepting the Total Commoditisation of Server Hardware and a Bigger Balance Sheet

The as-a-Service model outlined above does lead to four outcomes that could also be seen as challenges, ones that would need to be overcome for this to become the standard:

- It will finalise the commoditisation of server hardware as we know it, at least for traditional applications (not high-performance computing or tailor-made computing) by selling the resulting compute, memory, storage, and network capacity (potentially in low-, mid-, and high grades) per gigahertz (GHz), core, terabyte (TB)/DDR4, TB/NVM Express (NVMe), gigabit (Gbit), etc. – in other words, by specs and price.

- It will reshape the balance sheets of OEMs, keeping the assets on their own books and reducing large fluctuating revenues to more stable, but lower subscription-based revenues. It will also come with less manufacturing capacity needed, selling off production capacities and much more, ultimately leading to a more lean, resilient, and climate-proof business.

- It will understandably raise security and data ownership/stewardship concerns, particularly in terms of how servers will be wiped to guarantee sanitisation and how data transfer will work. If a vendor has ultimate control over a piece of IT hardware, such as a server, since it still technically owns it, what kind of safeguards would be needed in order to reassure customers that they are still in control of the data that hardware stores and processes?

- An IT Hardware-as-a-Service model may present new challenges to innovation and research incentives. If product life extension and standardisation become commonplace, for instance, what will drive vendors to pursue new, cutting-edge improvements and usher in the next significant change? And vendors must also be willing to extend software lifecycles as well, since firmware that is typically designed for shorter cycles will have to be maintained and improved over a longer time period as well.

The challenge of commoditisation has been a long time in the making. Looking at chips, for instance, which are “a layer down”, we have already seen massive consolidation and concentration in memory and computing chips (e.g., with AMD, Intel, Samsung, etc.). That issue has only been exacerbated by chip shortages and supply chain disruptions. At the same time, the value-add of OEMs has continuously shrunk and the sector has consolidated – who is really left today, for instance, beyond Dell EMC, Supermicro, Hewlett Packard Enterprise, and Lenovo? With the work that OCP is leading on, this commoditisation has already reached another peak. Thus, moving to an as-a-Service model can lead to the final standardisation of server equipment.

And despite many of the vendors already offering financing and leasing, it is done via a third-party or in-house banks, who are still ultimately “buying” the hardware and creating top-line revenue (albeit artificially). It is not the same as fully embracing an as-a-Service model as we are stipulating, nor does it seek to fundamentally address that, in order to create a sustainable digital economy, the underlying infrastructure has to be sustainable as well. This is applicable to both environmental and social sustainability, but also financial sustainability – if the business case for sustainability is not realised, as SDIA's Roadmap to Sustainable Digital Infrastructure by 2030 seeks to do, then the sector will continue to drag its feet.

Regarding the second challenge we outline, it will require proper financial restructuring and strong communication to shareholders on why the transformation is needed. Fundamentally, we believe it will lead to better ratings, it will lower risk for the business, and future-proof it for an ever-greater regulatory push toward a circular economy. What is encouraging is that, as time progresses, it is abundantly clear that environmental unsustainability is costly. It is also clear that there is a great opportunity for the IT Hardware-as-a-Service business model, and that can be taken up by a new actor – the service provider – which can be either a manufacturer or a third party. That entity becomes a market maker that helps optimise a fleet of hardware across suppliers and service consumers, further boosting job availability, skills, and device longevity.

In terms of security and data ownership, here is where markets and competition will prevail. The model we outline will require new levels of transparency that were previously seen as a disadvantage or uncompetitive. The IT Hardware-as-a-Service model, however, flips this dynamic entirely. The more transparent, accountable, and privacy-respecting a vendor becomes, the greater likelihood that they will be seen as a trusted partner – akin to how Apple has positioned itself as the market leader in respecting privacy. And as we have argued before, sustainability is built on trust and openness, where transparency is a significant facilitator of trust. Reliable and accurate data is therefore a vital ingredient in this process, which is why SDIA's Open Data Hub and the accountability it seeks to foster are also critical.

Lastly, while the fourth challenge is understandable, this is where modularity shines. If IT hardware is built in such a way that the components that are most likely to be replaced or upgraded can simply be swapped out for new, improved ones – along with the necessary software/firmware support – then competition will continue to fuel innovation. When coupled with the quality-of-service support, reliability, and the fact that the necessary transparency as highlighted above actually promotes innovation, IT hardware customers will have multiple reasons to continue demanding innovation and ultimately rewarding the vendor that can deliver. And given that governments are becoming increasingly supportive of longer life cycles, vendors would be better adapted to new policy and regulatory changes as well as maximising incentives and financial support for innovation.

Sustainability is Good for Business

In light of the Sustainable Development Agenda, the myriad pledges to address the climate crisis, and the various environmental challenges that we face in the 21st century, we have to see business model innovation as a critical part of the solution. But the good news is that, as I have said time and time again, sustainability is good for business – both in terms of profitability and customer satisfaction. Study after study demonstrates, for instance, that adopting sustainability practices decreases costs while making businesses more competitive. As far as the digital sector is concerned, the days of major hardware improvements year-on-year are over, but the time to take our IT hardware in a better, more sustainable direction is ripe.

Join us in our efforts to make this a reality, and ensure that the digital economy can better serve businesses that underpin its infrastructure and services, the people and communities it is meant to serve, and the planet upon which we are all relying.

Originally published on the SDIA blog.

Comments 0

The comments section is closed for articles published more than a year ago. If you'd like to inform us of any issues, please contact us.