We explore the status of the routing security and IPv6 adoption in the Arab countries in the Middle East highlighting how initiatives on RPKI, measurements, and capacity building are shaping a more secure, future-proof Internet.

As we publish this report, registration for MENOG 25 - which takes place in Dubai on 24-28 November 2025 - is still open!

The Arab countries in the Middle East have been accelerating Internet development, with governments and operators leading the efforts. Major progress has been made in deploying IPv6 to meet the modern-day requirements of resilient networks and routing security in the region. Embracing such technologies is crucial for such a diverse region to meet the demands of a large population and rapidly growing economies.

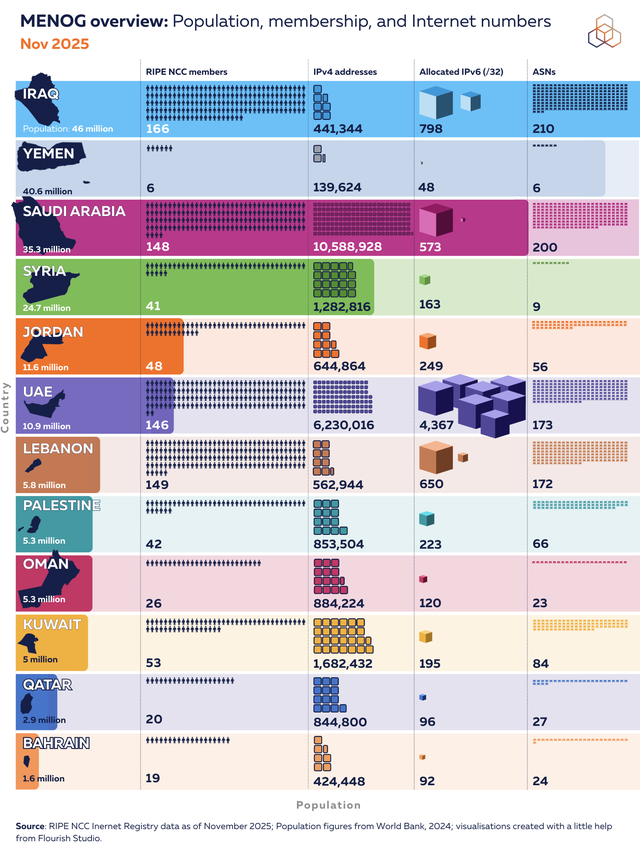

Internet numbers across the region

The availability of both IPv4 and IPv6 resources is increasingly important to meet rising demand and the transition to IPv6 has become essential for accommodating future growth. Breaking down the distribution of resources across the region, relative to population and RIPE NCC membership numbers, the following picture emerges:

Note that in this report, we're focusing on the Arab-speaking countries in the Middle East. The regional report we published in September ahead of the CAPIF 4 meeting provided an overview of the data we share here for Iran.

Although the distribution of such resources does not, in itself, give us a complete picture of Internet development, the overview reveals some noteworthy patterns. For instance, compared to their larger neighbours, we see that Kuwait and Lebanon have achieved relatively high resource density (in terms of IPv4 and IPv6 respectively), though Lebanon has more than double the number of ASNs and almost triple the number of RIPE NCC members.

Among the largest countries by population, Iraq shows a relatively strong footprint, with the largest membership among the countries analysed, and a diverse number of ASNs. In contrast, Yemen stands out for having very few members, a small IPv4 pool, and only 6 ASNs.

In terms of number of resources, Saudi Arabia is a clear outlier, pairing a large population with over 10.5 million IPv4 addresses and 200 ASNs. They also have a large number of IPv6 addresses in comparison to other countries analysed. But it is the UAE - with its large pool of IPv4 space, strikingly high volume of IPv6, and solid number of ASNs - that really stands out in this respect among the countries analysed.

RIPE NCC’s Engagements in the Middle East

In 2025, the RIPE NCC worked closely with governments, regulators, policymakers and intergovernmental organisations in the region on capacity building, IPv6 deployment, routing security and Internet measurements.

One highlight was the signing of the Joint IPv6 Declaration with the ITU at the Arab Regional Telecommunication Development Forum in Amman in February. The declaration establishes a coordinated framework to accelerate IPv6 deployment and support national digital transformation strategies. This was complemented by a new MoU with UNDP, signed during the Digital@UNGA week in September in New York, enabling cooperation on digital skills development, Internet measurements, and capacity-building programmes that support inclusive and sustainable connectivity across the Arab region.

At the policy level, the RIPE NCC actively contributed to the WSIS+20 review process, participating in the Arab WSIS+20 Open Consultations and High-Level Meetings, as well as the Geneva High-Level Event. Our engagement aimed to safeguard an open, interoperable global Internet while supporting Member States in shaping evidence-based digital policies. Cooperation with the League of Arab States also advanced through a joint initiative to integrate Internet measurement tools - RIPE Atlas, RIPEstat, and RIS - into regional policy analysis, strengthening data-driven decision-making across Arab ICT institutions.

In addition to a broad variety of engagements aimed at supporting national regulators, the RIPE NCC has also continued to deliver capacity-building programmes across the region, including targeted IPv6 and RPKI routing security workshops in Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Kuwait, and Jordan. These activities responded to regulatory priorities identified during the Amman Government Roundtable, where Arab ICT authorities highlighted the need to advance IPv6, secure routing, local traffic exchange, and technical coordination.

These initiatives underscore our commitment to supporting governments and policymakers in building secure, resilient, and future-ready Internet infrastructure, grounded in evidence-based best practices and multistakeholder cooperation. More broadly, our efforts on this front contribute to broader Sustainable Development Goals, as they help strengthen and maintain infrastructure - IPv6, RPKI, K-root - essential for innovation and development and support operators in building the skills necessary for them to enable digital transformation. These efforts have been widely supported in the Middle East, where we collaborate with several UN bodies in different areas.

MENOG 25 will help continue this work, and we’re also looking ahead to the ninth RIPE NCC Government Roundtable for Arab Countries in the Middle East, to be hosted by the Egyptian regulator on 4 December in Cairo, Egypt.

Routing security

RPKI allows IP address space holders to publish Route Origin Authorisations (ROAs), which specify which ASes are authorised to originate their prefixes. Through Route Origin Validation (ROV), networks validate BGP announcements against published ROAs, allowing them to reject announcements with unauthorised origin ASes and thereby mitigating prefix hijacks.

While the MENOG region continues to strengthen its routing ecosystem, RPKI and ROV remain essential. The global routing system relies on trust between networks, and BGP itself provides no built-in mechanism to verify whether an AS is legitimately authorised to announce a prefix. RPKI fills this gap by giving operators a cryptographic way to publish and validate origin information, turning what used to be implicit trust into explicit verification.

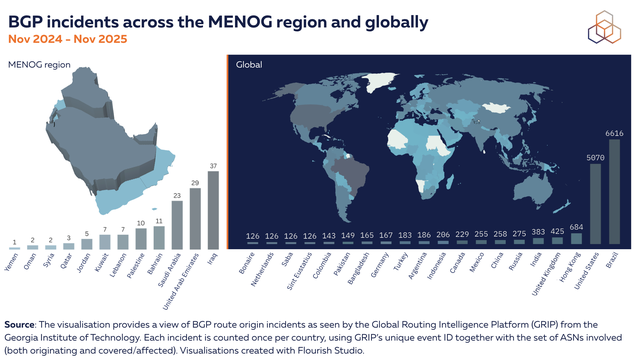

As the visualisation below shows, the number of BGP incidents we see for countries in the MENOG region is relatively low. But even with few visible incidents, the absence of ROV leaves networks vulnerable to accidental leaks or malicious hijacks that can spread rapidly across the Internet. The operational impact of such events is highly uneven: a single invalid announcement can affect critical services, government platforms, or large-scale consumer connectivity. This is why RPKI deployment is not only about reducing the number of incidents, but also increasing the resilience of networks when anomalies occur.

For more information on how we counted BGP incidents in GRIP, see notes at the end of this article.

As more operators in the region move from ROA creation to active ROV enforcement, the benefits become systemic: invalid announcements propagate less, recovery becomes faster, and operators gain more operational confidence in the stability of their routing policies. This system-wide shift is what ultimately determines whether local progress translates into regional routing security.

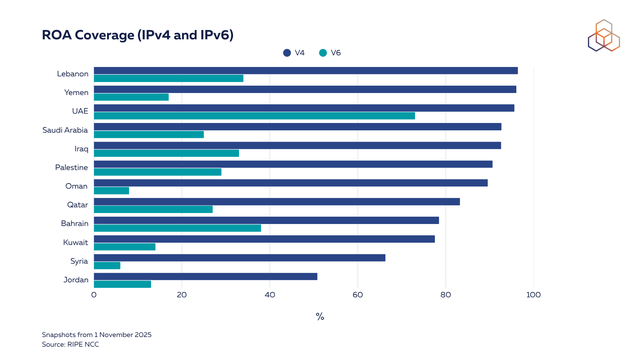

ROA coverage

The Middle East has strong RPKI adoption, with ROA coverage (IPv4 space) ranging from over 40% to nearly 100%. IPv4 ROA coverage consistently shows higher percentages across the region compared to IPv6, and yet there has been some growth in IPv6 ROA coverage over the past year.

As we reported last year, we saw greater RPKI adoption in some of the countries in the region following engagements between the RIPE NCC, local operators and the governments. For example, our engagements in the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Syria in the past two years led to a significant increase of ROA coverage in the country.

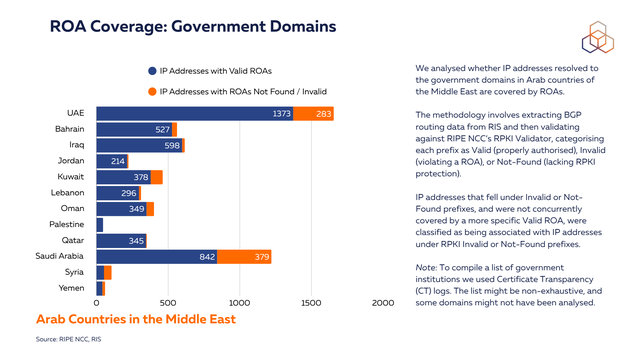

Securing government infrastructure

The Middle East is experiencing a major shift towards digital transformation, as governments and businesses adopt new technologies to boost economic growth and innovation. The United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia, and Qatar have been leading with ambitious digital initiatives. In all such initiatives, strong government infrastructure to support the digital agenda is key, and so to assess the security of the government domains in the region, we examined their resilience in routing security.

The graph below shows counts for IP addresses behind the identified government domains that are and are not covered by ROAs. To do this, we extracted the relevant BGP routing data from RIS and then validated against RIPE NCC’s RPKI Validator, categorising each prefix as Valid (properly authorised), Invalid (violating a ROA), or Not-Found (lacking RPKI protection). IP addresses resolving to these domains that fell under RPKI Invalid or Not-Found prefixes, without being covered by a more specific Valid ROA , were classified in the respective category (see methodology note at the end).

The results point to a high level of ROA adoption in government domains in the analysed countries. For example, in the UAE, over 80% of IP addresses resolving to government domains are covered by ROAs, while in Oman, the host country of the previous MENOG meeting, the percentage reaches almost 90%.

From authorisation to validation

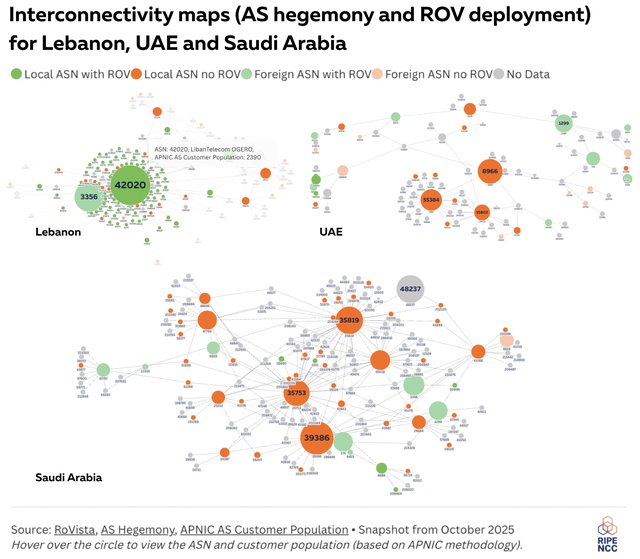

We further analysed the current state of ROV deployment in some of the countries in the region. As in our previous reports, we used the data from RoVISTA with a view of network centrality derived from AS Hegemony methodology, an approach that gives us a measure of the centrality of autonomous systems within a country.

For an interactive version of these visualisations, see the full Flourish visualisation (also embedded below).

Based on current RoVista measurements, we do not yet see major changes in observed ROV deployment in Saudi Arabia or the UAE. However, this requires additional context. RoVista has known limitations: it relies on the set of visible RPKI-invalid prefixes, it is influenced by upstream filtering, and it cannot reliably detect partial or site-specific deployments. For countries actively running controlled pilot programs, these limitations can obscure real operational progress.

In Saudi Arabia’s case, several developments are not yet fully visible in public measurements. Over the past year, a coordinated RPKI-ROV programme has been underway with operators and the national regulator, including on-site work as recently as late October. APNIC’s RPKI statistics (for SA) show ROA and ROV-related activity beginning to rise from effectively zero to around 12%, with the first signs of pilot-level validation visible in networks such as STC (AS25019) and Jawwal (AS39891). These patterns are consistent with controlled rollouts where ROV is enabled on selected gateways or geographic sites before being deployed network-wide.

Once these pilots are expanded across all operator sites, we expect ROV adoption in Saudi Arabia to become clearly visible in both measurement data and operational behaviour. Given the scale of the work carried out by the operators, regulators, and the RIPE NCC, it is important to reflect this ongoing transition, even if current measurement tools do not yet capture the full extent of the deployment.

In Lebanon, we have observed a positive change since our last report. OGERO/LibanTelecom (AS42020) has a high AS Hegemony score and has started to deploy ROV, thus providing comprehensive protection against invalid routes across Lebanon's routing infrastructure.

Overall, routing security in the MENOG region continues to show remarkable progress, with Arab countries in the Middle East emerging as strong adopters of ROAs and actively advancing their ROV deployment. This steady momentum reflects a growing commitment among operators and governments to strengthen the resilience of their networks.

Stronger IPv6 adoption

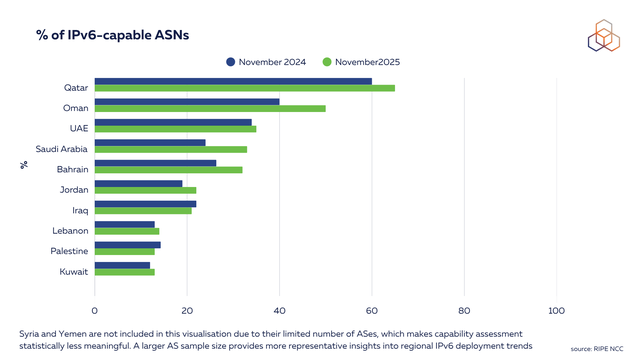

IPv6 capability per country here is defined as the percentage of ASNs routing at least one IPv6 prefix. While this doesn't necessarily reflect actual IPv6 traffic or user adoption, it does give an indication of routing readiness.

The Middle East is an excellent example of the region with a fast adoption of IPv6, with the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Qatar being among the top 20 countries in IPv6 adoption according to some CDN metrics.

Since MENOG 24, IPv6 capability has increased across most of the countries we examined. Oman, the host of MENOG 24, showed about a 10% rise. Qatar continues to lead at more than 60%, with the UAE and Saudi Arabia following closely. It is worth noting that Qatar and Oman each have a small number of ASNs, so their percentage values can look higher than in larger markets such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, or Lebanon.

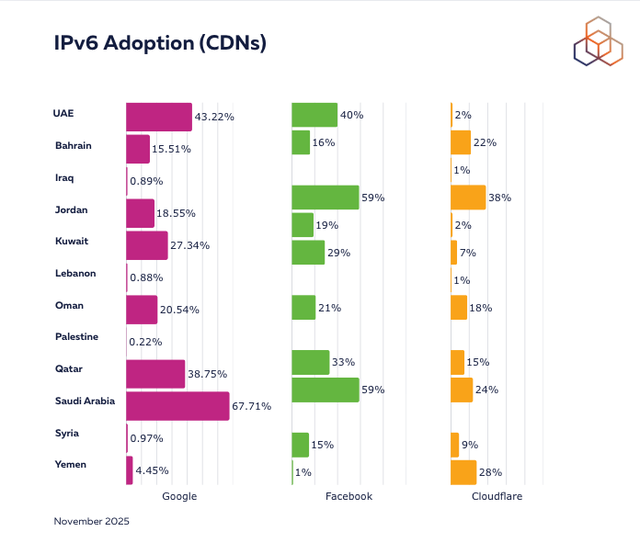

While IPv6 capability indicates the readiness of networks to use IPv6, actual adoption is not easy to measure. We looked at measurements reported by some major Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) on IPv6 adoption in the region. Recent data reveals varying levels of IPv6 adoption in the region.

The UAE, Saudi Arabia and Qatar are among the top adopters across all reported sources with the adoption varying between about 20% and 70%. Although the levels are not high in all countries in the region, the overall willingness of the regulators and operators to embrace the acceleration of IPv6 (as we reported earlier in the engagement section) suggest a strong commitment for a future-proof Internet landscape in the region.

As our continuous engagements with operators, regulators and government in the Middle East show, the region continues to accelerate digital transformation and accelerate secure and future-proof Internet infrastructure. If you are interested in insights from the renowned experts from the Internet community in the Middle East and beyond, join us at the upcoming MENOG 25 meeting.

Notes on methodology

- Government domains: To compile a list of government domains, we utilised Certificate Transparency (CT) logs, which are publicly accessible records of all issued SSL/TLS certificates. The primary tool for this is crt.sh, a web-based interface that allows for searching these extensive logs.

The methodology involves queryingcrt.shwith a wildcard search for a specific government top-level domain, such as%.gov.xx. This initial query retrieves all certificates issued for subdomains under that parent domain. The raw data from these certificates, including common names and subject alternative names, is then systematically extracted and normalised. This involves cleaning the data by removing wildcard prefixes (e.g., converting*.example.govtoexample.gov), splitting entries that contain multiple domain names, and standardising the text to create a clean, deduplicated list of unique government hostnames.

For each domain, we resolve both IPv4 and IPv6 addresses and check whether the resulting endpoints are covered by valid ROAs. Many of these domains are likely hosted behind CDNs or other third-party platforms. That means the ROA status reported may reflect the routing security practices of the hosting provider. This analysis is domain-based and limited to the ROA status of the resolved endpoints. In future reports, we plan to expand the analysis with a more detailed examination that distinguishes between government-operated infrastructure and externally hosted services.

- BGP incidents in GRIP: GRIP provides near-real-time observability of suspicious BGP routing events, including MOAS (Multiple Origin AS) - where the same prefix is announced by more than one AS - and sub-MOAS - an event in which an AS announces a more specific prefix that lies within a covering prefix announced by another AS.

Our analysis focuses on MOAS and Sub-MOAS events, as these can be mitigated by RPKI when invalid origins are detected, limiting their propagation in networks that enforce Route Origin Validation. To add geographic context, each ASN involved is annotated with its country of registration as recorded in the RIPE Database (noting that registration country does not necessarily reflect where an AS operates).

Comments 3

Milad Afshari •

The report, as always, is excellent and very accurate, particularly with the visualizations, which greatly help in organizing the data. However, one issue that still raises questions for me as an active member of the MENOG community is why, over the past few years, the reports have focused solely on Arab countries, excluding other Middle Eastern nations, including Iran. This kind of categorization makes us feel less connected to the community. While it’s true that Iran is included in CAPIF reports, we must not forget that with over 70 million internet users and substantial internet traffic capacity, Iran should not be overlooked in Middle East reports.

Qasim Lone •

Hi Milad - thanks again for the feedback. As we've mentioned in previous reports, Iran has been an active participant in CAPIF from the start. And indeed, looking back at attendance at our regional meetings last year, we saw that more Iranians attended CAPIF 3 than MENOG 24. These factors led us to once again focus on Iran in the report ahead of CAPIF 4 - and since that report was quite recent, we didn't want to duplicate numbers here.

Named •

It's interesting to see that Yemen, despite having a population of 40 million people, only has 6 ASN's. And as they have far less IPv4's than people, they must be relying heavily on carrier-grade NAT. In fact, all countries listed here must be using CG-NAT solutions, as they all have an IPv4 shortage. "The west" absorbed all IPv4 blocks at an early stage, leaving nothing left for other regions. If anyone can tell about the consequences brought by such an IPv4 shortage, i would love to hear about it. Also, I really hope that similar mistakes are not repeated for IPv6. While the amount of IP's is practically unlimited, there probably is a limit to the size of your routing table. How much can this table grow without performance or stability impact, and is this growth distributed evenly? If one region were to add a billion routes, could it lock out other regions from adding routes due to table limits? (I'm no expert on routing tables, but IPv4 exhaustion and 512k day pop up in my mind.)